Originally published Sept. 11, 2022

Stories From a Photojournalist Who ‘Made it Sing’

Homepage photo: Bruce Talamon shows the Journal-isms Roundtable a photo of himself with Earth, Wind and Fire. (Credit: Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks)

Bruce Talamon sits next to a photograph he made of Chaka Khan in 1977 at the Los Angeles

Coliseum during the P-Funk Earth Tour. (Credit: Mel Melcon/Los Angeles Times)

Stories From a Photojournalist Who ‘Made it Sing’

“I would like to think that I captured a visual history of R&B royalty,” photographer Bruce Talamon said, and when his seductive Journal-isms Roundtable presentation was done, one viewer said, “Bruce, the photos are incredible and your stories are even better.”

Editors tell young writers to “make it sing,” and Talamon showed that with the right subjects, honed skills and a musical connection, photographers can do that, too. Hard-nosed journalists filled the Zoom chat room with such comments as “These shots are incredible” “This is a great photo!” “I’m loving this!” “A front row seat to genius!” and “Truly MARVELOUS!!!”

Talamon went around the country in the 1970s photographing Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Bootsy Collins, Earth Wind and Fire, George Clinton, Labelle, Chaka Khan and other R&B and soul music stars of the time.

In 2018, Talamon collected the photos in a thick coffee table book, “Bruce W. Talamon Soul R&B Funk Photographs 1972 – 1982.“

Now he has an exhibit, “Hotter Than July,” at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, which opened in July.

Talamon gave us the photos and the stories behind them. He added his remembrances and images from Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign and some of the Black journalists on the trail.

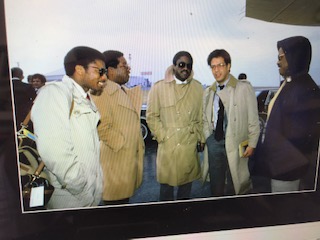

Covering Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign in New Hampshire: From left, Sylvester Monroe of Newsweek, Keith Moore of the Daily News in New York; George Curry of the Chicago Tribune; Jack E. White of TIme and Kenneth Walker of ABC News. (Credit: Bruce Talamon)

We saw the bulletproof vests that few knew protected Jackson in public, laughed with recognition when we recognized veteran journalists George Curry, Sylvester Monroe, Kenneth Walker, Keith Moore and Jack E. White and heard about The New York Times’ Gerald Boyd and Newsweek’s Jacques Chenier, who were also covering the Jackson campaign.

Same with the story of how Talamon was able to cover Jackson in the first place. The civil rights leader was a serious major-party presidential candidate, when, in those pre-Obama days, the significance of the candidacy didn’t compute with many news managers.

“This was the first time you had — I mean, you had the boys on the bus, but the boys on the bus didn’t have us,” Talamon told the group, which met on the afternoon of Sunday, Aug 28 . “And all of a sudden, it was like, you could not cover a presidential campaign unless you had covered a presidential campaign.

“But you couldn’t get out there unless somebody said you were OK. And all of a sudden, the newspapers and the TV people said, ‘well, what are we going to do now?’ And they scrambled. . . . you know, it was a crazy time, and it was wonderful. And I know in my case, when I went in to see Arnold Drapkin,” legendary director of photography at Time magazine, “and he asked me what I wanted to do, and I’m trying to be low key, and I said, ‘I’d like to cover the 1984 Democratic primaries’, and he started laughing.

“He says, ‘too late. I’ve got guys outside my door fighting, having fistfights over who’s going to cover Alan Cranston,’ ” the Democratic senator from California. “And I said, ‘I don’t want to cover Alan Cranston. I’d like to cover Jesse Jackson.’

“Nobody wanted to cover Jesse Jackson because — drum roll — they knew that he was going to leave, or should have left, after Super Tuesday, and they would have been out of a job. As it turned out, it was a crusade and we went all the way to the convention.”

There was more to Talamon’s struggle.

The photographer was in Hollywood, shooting Pee-Wee Herman, Steven Spielberg, Tom Hanks and others as they made their movies. He was that rare Black photographer on set, a circumstance he says still exists.

And when Talamon pitched the idea of a book of photos of reggae icon Bob Marley, 18 publishers rejected the idea and one wanted to use marijuana leaves to spell out his name on the cover.

“Soul R&B Funk Photographs 1972-1982,” the 375-page coffee-table book that is about to go into its third printing, was similarly a tough sell. While publishers had no problem producing picture books about white pop stars, no one had done anything comparable with Black ones.

The Journal-isms Roundtable took place by Zoom on Sunday afternoon, Aug. 28. Forty-nine people were on the call, with another 112 having watched on Facebook and YouTube as of Sept. 10. You can watch it above or on the YouTube site.

In addition, we toasted Yvette Cabrera, new president of the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and a reporter at the Center for Public Integrity, specializing in environmental justice, and Marquita Smith, who has been voted the Barry Bingham Sr. Fellowship for the journalism educator who has done the most for diversity. Marquita, Ed.D., is assistant dean for graduate programs at the University of Mississippi. Some may know her from her days at Knight Ridder, McClatchy or Gannett.

This session was the second Roundtable centered on photography. In February, the topic was photojournalists of color, co-sponsored by the National Press Photographers Association. More on that later.

Talamon’s concerns about the lack of diversity among movie-set crews are shared by his union, Cinematographer’s Guild Local 600 (I.A.T.S.E.). Xiomara Comrie, a business representative for the Guild, described for Journal-isms a tight-knit club of freelancers who hold those jobs, saying, “people are very happy and comfortable to work with who they want to work with.”

Talamon told us, “There are so many African American filmmakers and so many who don’t know that Black still photographers exist. Who say, ‘we didn’t know there were any Black still photographers,’ and it pisses me off, quite frankly. And it’s hard to change that. I used to tell folks when I would walk on the set that the only thing that were Black were me and my camera.”

In the post-George Floyd era, the I.A.T.S.E. won diversity pledges from the studios, but after contract negotiations last October, the union said only that “The agreement also includes unspecified diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives and adding Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a holiday,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

Since the rejections of the Marley book idea that in 2005 became “Spirit Dancer,” there has been movement in the publishing industry. When Dana Canedy stepped down in July as the first Black woman to serve as publisher of Simon & Schuster’s flagship imprint, Elizabeth A. Harris and Alexandra Alter reported for The New York Times, “The announcement came amid an industrywide push to increase diversity. Several major publishing houses have over the past two years hired and promoted people of color into prominent editorial roles, including Lisa Lucas, the first Black publisher in Pantheon’s 80-year history, and Jamia Wilson, vice president and executive editor at Random House.”

At the Roundtable, the emphasis was on photos and stories.

Alberta Gay told Bruce Talamon, ” ‘Darling, you can take your pictures, but you have to sit down and break some bread with us.’” Frankie Gaye is at left; Marvin Gaye at right. (Credit: Bruce Talamon)

Stories such as when Talamon accompanied candidate Jackson when he had dinner after a sleepover at the home of a family on the campaign trail, or when Marvin Gaye’s mother, Alberta, made supper for Marvin and his brother, Frankie, whose observations after returning from the Vietnam war inspired Marvin’s classic 1971 album “What’s Going On.”

“I spent nine days with him, and this was on his ranch,” Talamon said as he showed an image of Marvin. “And, he was a rock star. Let us be clear. He did live that rock star life.

“He was extremely generous — there he is driving his Rolls.

“On his way to his mother’s house. He said we gotta have lunch and the best place to have lunch is — I know a place. I’ll just tell you, there’s nothing better than day-after leftover Thanksgivng dinner. Mrs. Gay was so happy to see us because her boys were home. That’s Frankie on the left, and Marvin, and she set a place for me. She said, ‘Darling, you can take your pictures, but you have to sit down and break some bread with us.’ And she had the same overcooked green beans like my mother, and the Wonder bread, and it was fabulous. . . . but it’s also sad, because this was the house that his father killed him in in 1984. We found out about it when we were on the road with Jesse.”

— Shots of audiences mesmerized by Michael Jackson and his brothers in the Jackson Five: “Before Michael Jackson conquered the world, he belonged to little Black girls, and folks need to know that.”

When Ebony magazine asked Donna Summer whether she had a photographer that she would like to shoot with, she said “yes, Bruce Talamon,” the photographer recalled. He said he purposefully cropped out the heads of the men in the background. (Credit: Bruce Talamon)

— When Donna Summer was so impressed with Talamon’s session with her that she asked for him again, and provided his first national magazine cover photo. “They told her we would have 20 minutes. The shoot was set for 3:00 p.m. Donna showed up early. She saw our setup and stayed 4 hours. Months later, she requested us for her Ebony cover,” he explained later on Twitter.

— Up all night with Wonder and friends celebrating his birthday. The title of Talamon’s exhibit comes from Wonder’s 1980 album.

— The importance of the newspaper Soul, which “started in 1966 after the Watts rebellion,” and continued weekly, then every two weeks, until 1982.

Talamon was introduced to publisher Regina Jones by Howard L. Bingham, “whom some of you may know as Muhammad Ali’s photographer in Life magazine. . . . She gave Leonard Pitts,” the syndicated Miami Herald columnist who participated in the Roundtable, and Bruce Talamon some of their early jobs.”

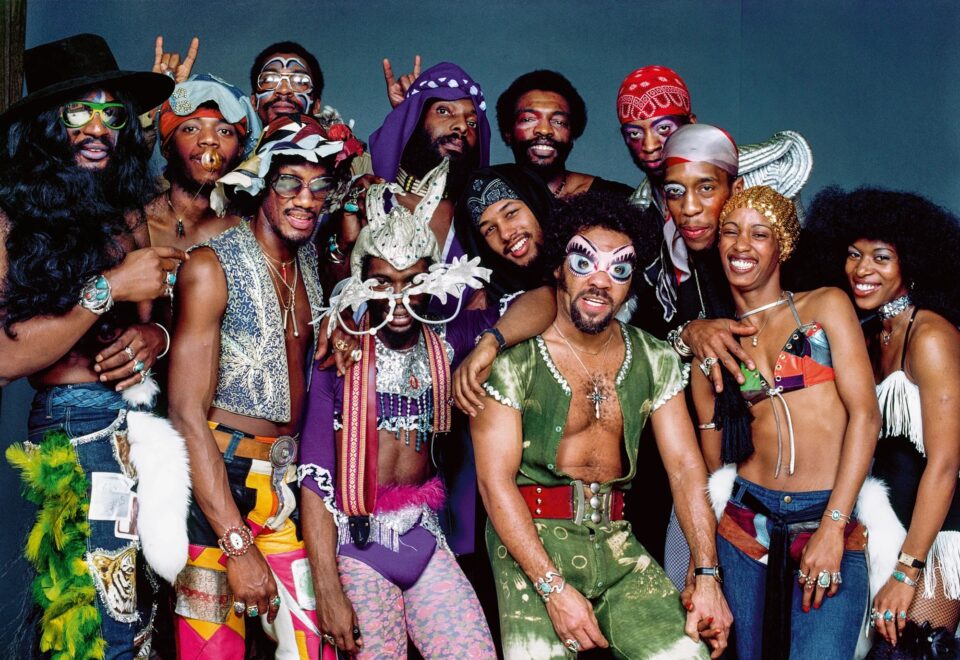

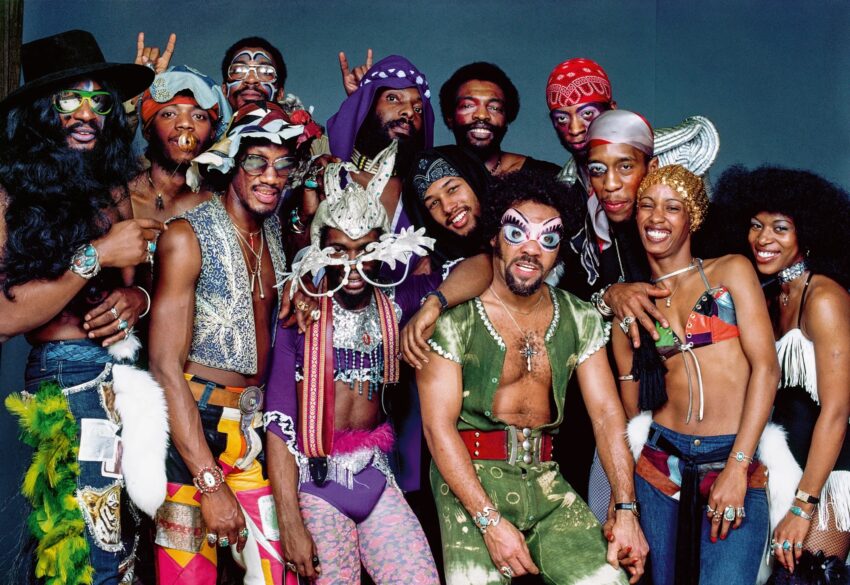

Parliament-Funkadelic at the Los Angeles Sports Arena in 1977. “You have never lived until you’ve tried to wrestle 13 people onto a 10-foot backdrop when they’re high,” Bruce Talamon said. (Credit: Bruce Talamon)

— Filming the 1977 P-Funk Earth Tour, with Clinton, Khan, Collins, Rick James and others. Of Parliament-Funkadelic, Talamon explained to the Roundtable, “I will just say to aspiring photographers and others, you have never lived until you’ve tried to wrestle 13 people onto a 10-foot backdrop when they’re high.”

— Telling the studio that presented the 1989 film “Harlem Nights,” with Eddie Murphy, Redd Foxx and Richard Pryor, that Foxx had to be included in the shot they wanted of Murphy and Pryor, which framed three generations of Black comedic history. Talamon’s judgment prevailed.

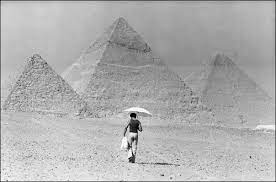

— The story behind a photograph of Maurice White of Earth, Wind and Fire, who became a friend he called ” ‘Reese,” walking toward the pyramids of Giza.

“And it became his favorite, and when he died, this went all over the world.”

Along the way, there were tips a photographer learns, and others that apply to all creative people.

“You’ve gotta stand up for yourself. I don’t mean to belabor the point, but I learned that from Sylvester Stallone. I was working on a movie with him, and I said something wiseass. . . . He says, ‘Bruce, I used to leave the driving to somebody else. But when your name is on it, you’re responsible for it.’

“One thing I would say to young or mid-career photographers to think about. You know, to get the knowledge because . . . it is crazy out there and it is treacherous.”

- Kimberlee Buck, Los Angeles Sentinel: The Rise and Fall of Soul Newspaper (July 27, 2016)

- Makeda Easter, Los Angeles Times: Photographer Bruce Talamon captured black joy in the glory years of soul and funk. Now he’s getting his due (Dec. 6, 2018)

-

Killian Fox, the Guardian: Behind the scenes with the biggest soul stars of the 70s (July 22, 2018)

-

Jeff Slate, Grandlife: Through the Lens of a Legend: Bruce Talamon Gets the Shot

‘They’ll Just Throw You in Jail’

-

Eugene Tapahe writes, “From April 2016 to February 2017, thousands of people from all over the world have gathered to protect our water. The Dakota Access Pipeline was planned to cross the Missouri River, the lifeline of 18 million people who rely on it for water. This is for our future, our survival, and for all humanity.” (Credit: Eugene Tapahe/ Tapahe Photography)

Photojournalists of Color Relate Their Challenges

Eugene Tapahe, Navajo, a designer, artist and photographer who specializes in the landscape and people of the Southwest, was describing a key difference between himself and photojournalist of other ethnic groups.

“It’s really easy as a journalist to be thrown in jail as a Native American,” Tapahe told the Journal-isms Roundtable.

“You tell them you’re a journalist. You tell them everything. You show your credentials, but they don’t care.

“They’ll just throw you in jail, you know, and I think that’s the part that’s different between minorities. The Black association and all that, it seems to have more power because you have more people. But when it comes to Native Americans and in the journalism fields, we get treated a lot worse than a lot of other journalists, just because . . . even in America, the history of America makes us feel like, you know, like we are still not part of society.”

Tapahe was asked whether this was true across the country or specific to certain parts.

It’s universal, he replied. On the East Coast, “it’s even probably even worse, just because there’s a lot less Natives there, and so there’s a lot of uneducated people about Native people.

“As you get closer to the reservations it becomes more hatred, because of border towns and because of the relationship between non-Natives and Natives.

“When you get further away from the reservation, it’s more uneducated and naive people.

“But when you get closer to reservations, it’s more hatred and more focused on, ‘Oh, OK, we don’t want them to prosper.

” ‘So this is how we’re going to treat them even if it is photographers, or maybe especially the photographers.’ . . . because we can capture the moment, you know, either video or camera. . . . It’s like they look for you . . . because if you’re a writer you can write and not be seen. . . .

“But as a photographer, you’re standing there with a camera or a video camera, whatever you’re doing, and they can focus on you and pull you out of the crowd.

“And . . . even with your credentials . . . showing, it still happens.

“That’s what happened in Standing Rock a lot, when we were on the front lines a lot. . . .”

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and its supporters have been protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Some 75 were on the Zoom call, with another 108 tuning in on Facebook.

Tapahe was speaking at a Journal-isms Roundtable on Feb. 27, just before the Russian invasion of Ukraine dominated the headlines. The event was co-sponsored by the National Press Photographers Association.

Some 75 were on the Zoom call, with another 108 tuning in on Facebook. You can watch the video above or on the YouTube site.

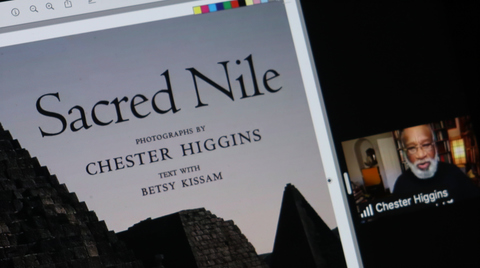

The Roundtable was highlighted by a presentation from Chester Higgins Jr. (pictured), retired New York Times photographer who pursued what’s been his passion since his first visit to the Nile Valley in 1973. His coffee-table book “Sacred Nile” looks at “what I would call the world before Genesis. . . Our history did not begin at the bottom of a slave ship,” he told the group.

The Roundtable was highlighted by a presentation from Chester Higgins Jr. (pictured), retired New York Times photographer who pursued what’s been his passion since his first visit to the Nile Valley in 1973. His coffee-table book “Sacred Nile” looks at “what I would call the world before Genesis. . . Our history did not begin at the bottom of a slave ship,” he told the group.Just as Higgins recognizes that there was more to the ancient world than Greece and Rome, so does Hyungwon Kang, photojournalist and columnist who said he has been documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations.

“I am a Korean American, born in South Korea, but grew up in Los Angeles. . . . Even when I was attending UCLA, I couldn’t believe how ignorant my political science professors were when it comes to history and knowledge about ancient civilizations of the Asia,” Kang said, “and for the next 33 years, when I worked in the mainstream media at the L.A. Times, the A.P. and Reuters, I ran across just countless occasions where . . . absence of knowledge about Korean culture and civilization was interfering with the storytelling in America.

“So I corrected what I [could] when I was working, but as soon as I retired from Reuters, I jumped in this project called “Visual History of Korea,” where I’m making first impressions with pictures about Korean history and culture like what Chester Higgins has just done for the last 50 years.” He has a book deal, he said. (Photo of Kang at Buyeo National Museum, South Korea)

Surfacing suppressed pasts is just one way photojournalists of color are bringing diversity to their chosen field.

Maria DeJesus (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), president of the National Press Photographers Association and photographer at the Houston Chronicle, said that her identity, “as a Puerto Rican woman, queer, I think it gave me an ability to be extra sensitive to the scenes that I encounter.” DeJesus thinks of Hurricane Maria, the deadly Category 5 hurricane that devastated the northeastern Caribbean in September 2017.

Maria DeJesus (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), president of the National Press Photographers Association and photographer at the Houston Chronicle, said that her identity, “as a Puerto Rican woman, queer, I think it gave me an ability to be extra sensitive to the scenes that I encounter.” DeJesus thinks of Hurricane Maria, the deadly Category 5 hurricane that devastated the northeastern Caribbean in September 2017.“Every time that I go to a crisis,” she said, she imagines how she would expect journalists to treat her parents on the island during such a tragedy.

“That type of sensitivity, type of respect, empathy. I think that I bring a warmth that it’s very traditional, and . . . normal in my people. Puerto Ricans, we tend to be very empathetic, very open. And I think that that’s one of the most wonderful things I bring to the table as a Latina photographer.”

For Black photojournalists, issues include representation and lack of positive images, as well as the trauma of covering so much Black grief. That hit a high point with the 2020 police killing of George Floyd.

Monica Herndon (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), a Philadelphia Inquirer photographer, worked on the newspaper’s “Wildest Dreams” series, which the Inquirer describes as “a collaborative mini-anthology of storytelling about Black cultural inheritance, legacy, and joy. Presented by a team of Black journalists at the Inquirer, the project celebrates the vastness of Black imagination and honors the gifts imparted to us by our ancestors — many of whom couldn’t live out their fullest dreams.”

Monica Herndon (pictured, by Sharon Farmer), a Philadelphia Inquirer photographer, worked on the newspaper’s “Wildest Dreams” series, which the Inquirer describes as “a collaborative mini-anthology of storytelling about Black cultural inheritance, legacy, and joy. Presented by a team of Black journalists at the Inquirer, the project celebrates the vastness of Black imagination and honors the gifts imparted to us by our ancestors — many of whom couldn’t live out their fullest dreams.” “Visions of Black Joy” was the idea of Danese Kenon, Inquirer managing editor, visuals, who also joined the Roundtable.

For its part, in 2018 The New York Times hired Brent Lewis as a Times photo editor.

Lewis is a co-founder of Diversify Photo, a company formed in 2017 that maintains a global database of 1,000 photographers of color, with another 400 “who are not quite there at membership level, but they’re gonna be making fire in the next year or two years, Lewis told the group. “It’s just a matter of being super-intentional, right, in who you mentor, and how you affect the world,” he said.

Jarrad Henderson, a Black multimedia producer at USA Today, asked fellow photographers, “Last year wasn’t a time to kind of break, but I’m curious . . . how have you been intentional about stepping away,” especially since it “kind of seems like a badge of honor sometimes to not step away and to take those bumps and bruises.

“But now . . . we’re so conscious about mental health and balance and all those things.” Should we “like, you know, photograph puppies for a while, or just [do] something that allows you the mental break that you need to kind of like reset, maybe?”

Herndon of the Inquirer had already given her answer: “I think that young journalists look at the world a lot different than more veteran journalists . . . . Sometimes I know that I have to look out for my own mental well-being more than the work . . .”

Carl Juste (pictured), who is of Haitian and Cuban background, has worked at the Miami Herald since 1989 and also maintains his own photo collective. He applied for a grant to create “Defiance: An Exhibition of Open Resistance and Bold Disobedience – An exhibition that features several photojournalists and includes panel conversations and workshops to re-examine the local implications of George Floyd’s death and discuss race, police brutality, and how the community can move forward.”

Carl Juste (pictured), who is of Haitian and Cuban background, has worked at the Miami Herald since 1989 and also maintains his own photo collective. He applied for a grant to create “Defiance: An Exhibition of Open Resistance and Bold Disobedience – An exhibition that features several photojournalists and includes panel conversations and workshops to re-examine the local implications of George Floyd’s death and discuss race, police brutality, and how the community can move forward.”“I think is really important that as a journalist, but more important, not just as a Black journalist, as someone who’s trying to find some sense of truth, that sometimes you have to go into the belly of the beast and [muster] the courage. . . . There was not a foot on my neck [for] 8 plus minutes, but it’s been 40 years of collective trauma that I have to deal with between those times of Floyd, and you can name the next person that may . . . be a victim of brute of police brutality or an unjust system. So that’s how I tend to approach it. . . .”

The gathering was a mix of generations, opening with a tribute to the legendary photographer Gordon Parks, and honoring broadcast journalist Geoff Bennett (pictured), then recently named host of “PBS News Weekend.”

The gathering was a mix of generations, opening with a tribute to the legendary photographer Gordon Parks, and honoring broadcast journalist Geoff Bennett (pictured), then recently named host of “PBS News Weekend.”“My era of journalists, we’re all sort of coming into our own at the same time,” said Bennett, who turned 42 on April 25. “Yamiche [Acindor] at NBC. Abby Phillip at CNN. Aisha Rascoe was just named a host of ‘Weekend Edition Sunday’ at NPR, which is a show I used to be editor of back when Liane Hansen and Rachel Martin were hosts of that show.

“Kenneth Moton and Rachel Scott over at ABC. Weiija Jiang at CBS. So I’m glad to be in that number, and we collectively have you folks to thank for knocking down doors to make our path a little easier. So I appreciate that.”

Joining the conversation from an airport in Minneapolis was an appropriate spokesperson for media diversity, Sarah Glover (pictured, from Twitter), who was two-term president of the National Association of Black Journalists.

Joining the conversation from an airport in Minneapolis was an appropriate spokesperson for media diversity, Sarah Glover (pictured, from Twitter), who was two-term president of the National Association of Black Journalists. Glover became the newsroom’s managing editor at Minnesota Public Radio news in April 2021, after being managing editor of social media strategy for NBC Owned Television Stations. In June, WHYY in Philadelphia announced that Glover would lead its radio, TV, and digital news operations.

Glover looked around the Zoom room, shared anecdotes about the mentors and role models she saw as she thanked them, and said that she would always consider herself their colleague.

“I’d actually prefer to be on the street, and I probably will be again one day,” Glover said.

“But in the meantime, between time, I also recognize the value and need [for] more of us to be in managerial roles. . . .

“I am a champion of others, and I will be your biggest cheerleader. . . .

“I just hired my first Indigenous reporter last month, Matthew Holding Eagle the Third, and I wrote him a note last week, and I said, ‘I will be your biggest cheerleader.’

She continued, “My Asian brothers and sisters.

“My black brothers and sisters, my Indigenous brothers, sisters; my Latino brothers and sisters, my white brothers and sisters.

“I will be everybody’s biggest cheerleader and so you know I do that because of you, what you all have poured into me. . . .”

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

groups.io View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

Page views as of Sept. 17, 2022: 442