‘Demand’ at Newsday Led to Hiring of Les Payne

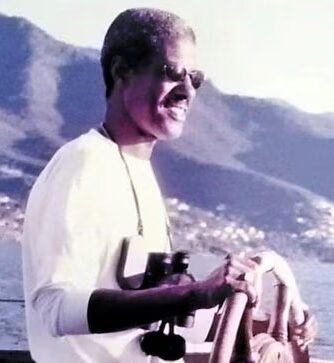

Homepage photo; Les Payne, John Lewis and Bill Moyers at SUNY Old Westbury at 2015 anniversary celebration. (Credit: Bob Giglione/SUNY Old Westbury)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Donations are tax-deductible.

Les Payne, left, moderated a discussion of “The Future of America: Race and Class” with Rep. John Lewis, D.-Ga., and Bill Moyers, at right, at a 50th anniversary celebration at SUNY Old Westbury on Nov. 12, 2015. (Credit: SUNY Old Westbury)

‘Demand’ at Newsday Led to Hiring of Les Payne

Bill Moyers, who died Thursday at 91 after battling prostate cancer, was a confidant of President Lyndon Johnson and spent more than 40 years chronicling and commenting on America’s ills as a broadcast journalist, all duly noted. But flying under the radar of the obituary writers was Moyers’ role in bringing diversity to the newsroom at Newsday, where he spent three years as publisher.

The late Les Payne, an icon among Black journalists as a columnist and newsroom manager, messaged Journal-isms in 2017, “My hiring at Newsday, along with six other blacks was demanded by Newsday publisher Bill Moyers, who, as you know, sat at the right hand of LBJ not only as his press secretary but also as his brain on progressive race policy,” referring to Lyndon Baines Johnson.

The message concerned the then-upcoming 50th anniversary of the findings of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner report, which examined the causes of the urban rioting convulsing the country in the late 1960s. The overwhelming whiteness of the media received some of the blame.

“Having been in the White House during discussion of the ’65 Watts riots, and privy to early planning stages of the commission, including the selection of Gov. Otto Kerner, Bill Moyers, of Marshall, Texas, was surprised at the racist policy on Long Island at Newsday and the press in general — so he set aside . . . six, non-competing slots for black reporters,” Payne wrote. “His hiring plan met enormous pressure from his top Newsday editors and Moyers . . . himself was subsequently fired with the bitter slander by the owner that he was a pinko liberal misfit for lily white Long Island.”

In his 1990 book, “Newsday: A Candid History of the Respectable Tabloid,” Robert E. Keeler picks up the story.

“Newsday had not hired its first black reporters until Tom Johnson and Pat Patterson in 1963, and the numbers had remained minuscule.

“In 1969, Moyers had made a push to hire six minority reporters outside the normal budget, but the people that Newsday hired eventually looked at this minority recruitment effort.”

Bill Moyers, in dark suit, with his very white newsroom in his role as publisher. (Credit: Newsday)

For a 2009 master’s thesis at the University of Missouri, Lourdes Fernandez Venard added, “Payne immediately organized Newsday’s Black Caucus and started pushing to recruit more journalists of color. In 1971, Payne wrote a memo noting that of 33 summer interns at Newsday, none was black. In the memo, he called Newsday’s editors racist.”

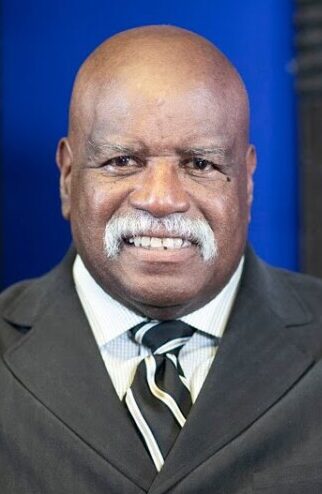

Keeler continued in his book, ” ‘What was immediately clear to us is that we were not being treated the way other reporters were being treated,’ said Les Payne, one of the original six. ‘This program of setting aside six slots kind of became an informal training program.’ That left them considerably short of equality. ‘ I think some our white colleagues — not all of them — sort of looked at us as if the only reason they hired us was for image,’ said Michael Alexander (pictured) who came to Newsday with a journalism degree from Ohio State.

Keeler continued in his book, ” ‘What was immediately clear to us is that we were not being treated the way other reporters were being treated,’ said Les Payne, one of the original six. ‘This program of setting aside six slots kind of became an informal training program.’ That left them considerably short of equality. ‘ I think some our white colleagues — not all of them — sort of looked at us as if the only reason they hired us was for image,’ said Michael Alexander (pictured) who came to Newsday with a journalism degree from Ohio State.

“So the black reporters began meeting as a caucus and discussing their concerns. One of their earliest joint efforts was a short note to the editors in 1970, protesting the overuse of the term ‘black militant.’ Then they sought permission to attend a convention of black journalists in Missouri. . . .

” ‘The whole idea we argued to [editor David] Laventhol was that we found ourselves in a hostile situation,’ Payne said, ‘that we were all rookie reporters, for the most part, that we were not treated fairly and we could not relate to the experience of white younger reporters at the paper.’ The Missouri conference was important, they argued, because senior black journalists would be there, and they could share information on how to deal with their common problems.”

Current diversity figures were not immediately available, but last September, Managing Editor Rochell Sleets, a Black journalist, became Newsday’s top editor.

Laventhol said he would permit three of the group to go, but the Black reporters insisted on all nine because, they contended, the importance of the meeting was not what was said, but the interaction of Black journalists. Laventhol conceded the point.

“So nine black reporters and photographers from Newsday became the largest single group at the conference, which played a major role in the development of the National Association of Black Journalists,” which was founded in 1975. Payne became a co-founder and its fourth president.

“Laventhol’s decision didn’t please some of the white staff members who put a note on the bulletin board,” Keeler wrote. ” ‘It said there was going to be an Italian-American meeting somewhere, and they wanted to send all the Italian reporters,’ Payne said. ‘There was resentment.’ But Laventhol emerged from this awakening of the black caucus with a decent working relationship with them. In his first turbulent months, that was enough.”

Also in that summer of 1970, Moyers greenlit a suggestion for a project called “the Summer Journal of Morton Pennypacker,” an “experimental supplement that would take the younger journalists at Newsday, give them complete freedom, and allow them to publish things that no traditional newspaper would touch,” Keeler wrote.

“Moyers resigned before he had a chance to implement the idea, but Laventhol decided to go ahead with it. . . .

“Perhaps their most impressive effort was a serious, powerful piece about migrants, by Payne . . . To find out about conditions in the migrant camps on the East End, Payne went undercover, calling himself ‘Bubba;’ and living with the migrants. His story, ‘Waiting for the Eagle to Fly,’ captured brilliantly the rhythms of their speech and the shape of their lives. “

Moyers left Newsday in 1970.

As Janny Scott reported in her New York Times obituary, “Moyers had strengthened the paper’s Washington coverage, added international bureaus and hired Saul Bellow to cover the 1967 Mideast war. The paper won two Pulitzer Prizes during his tenure. But its conservative owner, Harry F. Guggenheim, said to be annoyed by the ‘left wingers’ running the paper, sold his majority share in 1970, having turned down a higher offer from Mr. Moyers, who resigned.”

Payne’s colleague and friend Peter Eisner later wrote, Payne became “national editor, assistant managing editor for foreign and national news, and, at various times on his watch, he was in charge – often concurrently – of health and science coverage, New York City, Washington, politics, foreign reporting and investigations.”

Payne wrote a column for 28 years.

Current diversity figures were not immediately available, but last September, Managing Editor Rochell Sleets, a Black journalist, became Newsday’s top editor. She succeeded Don Hudson, the first Black journalist in the role, who was named in 2022.

‘We Are, as Latinos, Quite African’

June 27, 2025

En espanol: ‘Somos, como latinos, bastante africanos’

Reporting on Black-Hispanic Ties Needs Work

Journal-isms Roundtable photos by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Donations are tax-deductible.

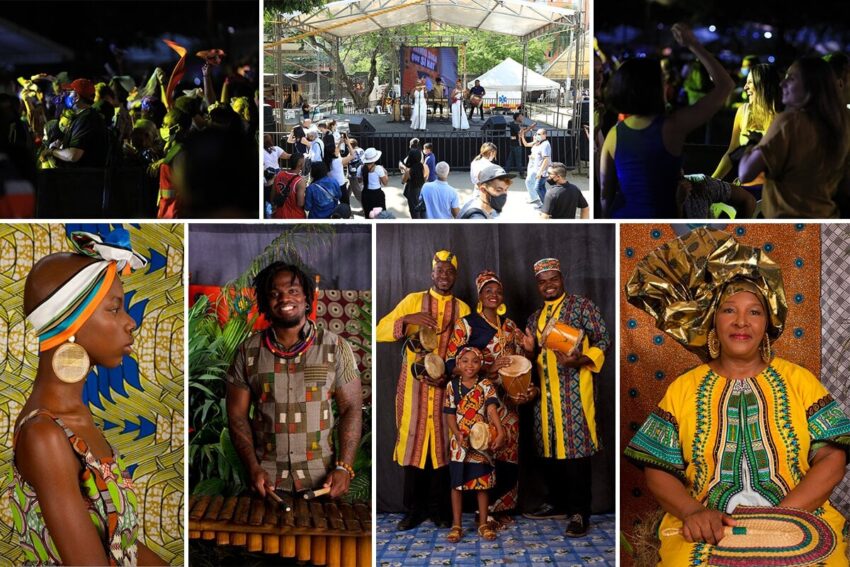

Each year, the city of Cali in Colombia celebrates the Petronio Álvarez Pacific Music Festival, a four-day tribute to Afro-Columbian traditions and culture. (Credit: Lisa Palomino/courtesy Ministry of Culture)

Reporting on Black-Hispanic Ties Needs Work

By Marcia Davis

“Should Black people care about ICE?”

It’s that kind of question that has some African Americans shaking their heads: “No, it’s not our fight.”

Others say, “Of course, we should care.” Many feel a natural instinct to support the underdog. They’ve been there.

Moreover, raids from ICE — U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement— have affected Black people from Haiti to Africa.

Those of Latino origins have varying views. Though many Latinos who voted for now-President Trump have said they approve of the president’s handling of illegal immigration, a coalition of national Latino and civil rights leaders held a virtual press conference this month to condemn the recent immigration raids in Los Angeles. They decried the federal government’s decision to deploy military force in local communities, despite opposition from local officials and residents.

And yet, the wide gap between Black and Latino voters in the presidential election had some wondering whether the coalition is fraying. “The election result of a week ago is evidence that the vision of a rainbow coalition as a political organizing principle is fading,” Charles M. Blow, who is Black, wrote in November for The New York Times.

“It’s evidence that many Americans are willing to subordinate racial and gender concerns when faced with unrelenting language about a lack of physical, economic and cultural security.”

In the 2024 presidential election, nearly half of Latinos (46%) voted for Trump. The percentage was even higher (55%) among Latino men. “That’s a bizarre turn of events for a constituency that was, just 20 years ago, considered a loyal part of the Democratic base,” wrote columnist Ruben Navarrette, who is Latino.

By contrast, about eight in 10 Black voters supported Democrat Kamala Harris, though that figure was down from the about nine in 10 in the last presidential election who went for Joe Biden, the winning Democrat.

According to some Latino observers, such as Navarrette and Democratic strategist Chuck Rocha, many Latinos felt the Democrats weren’t speaking their working-class language.

The similarities and differences between the two groups was the topic of February’s Journal-isms Roundtable, which posed the question, “Are the media accurately covering Black-Latino relations?”

The session took place at Syracuse University’s S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Newhouse DC, which co-sponsored the Washington event. Beverly Kirk, director of Washington programs, led the collaboration for Syracuse.

The Roundtable attracted 53 people in person or by Zoom. Another 175 watched on Facebook and 320 had seen the YouTube version by June 25. Click to view.

The panelists were:

Marie Arana, Peruvian American former editor of the Washington Post’s Book World section, inaugural literary director of the Library of Congress and author of three books on Latin America.

Marie Arana, Peruvian American former editor of the Washington Post’s Book World section, inaugural literary director of the Library of Congress and author of three books on Latin America.

Karen Juanita Carrillo, reporter for the New York Amsterdam News and author of the 2017 book, “African American–Latino Relations in the 21st Century: When Cultures Collide.”

Karen Juanita Carrillo, reporter for the New York Amsterdam News and author of the 2017 book, “African American–Latino Relations in the 21st Century: When Cultures Collide.”

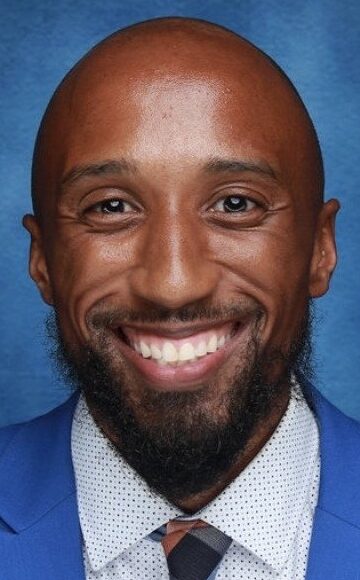

Torrance Latham, news editor at the Miami Herald, which is published in a city that is a locus for Latin American immigrants; its staff includes a race and culture writer, an immigration team and a Caribbean correspondent. Latham is also vice president of the South Florida chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists.

Torrance Latham, news editor at the Miami Herald, which is published in a city that is a locus for Latin American immigrants; its staff includes a race and culture writer, an immigration team and a Caribbean correspondent. Latham is also vice president of the South Florida chapter of the National Association of Black Journalists.

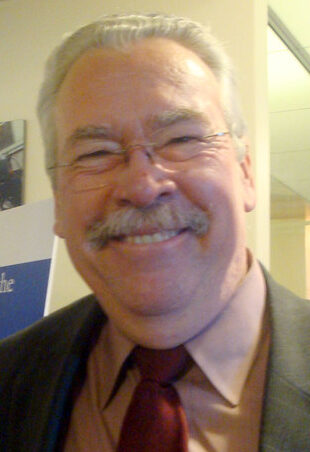

Don Podesta, retired editor and Latin American correspondent for The Washington Post, who was born in Chile and spent much of his childhood in Colombia before coming to the United States as a teenager. Podesta has lived or worked in almost every Latin American country.

Don Podesta, retired editor and Latin American correspondent for The Washington Post, who was born in Chile and spent much of his childhood in Colombia before coming to the United States as a teenager. Podesta has lived or worked in almost every Latin American country.

Roland E. Roebuck, president of the D.C.-based Afro Latino Institute and a native of Puerto Rico.

Roland E. Roebuck, president of the D.C.-based Afro Latino Institute and a native of Puerto Rico.

The conversation covered everything from colorism to genocide to education. To the question at hand — “Are the media accurately covering Black-Latino relations?” — for the most part, the answer was no. Some exception was given to the Miami Herald.

The “no” was particularly true about Afro-Latinos, a group for which coverage has been nearly nonexistent, they said.

According to the World Bank, one in four Latin Americans identifies as being of African descent. They are one of the largest, yet least visible minorities in the region, comprising more than 133 million people, the majority living in Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico and Venezuela.

At root of the Afro-Latino issue is the villainous hegemony of white supremacy.

“It’s remarkable to me that we would talk about Afro-Latino relations because we are, as Latinos, quite African,” said Arana. “We are actually — a good half of us — can trace a blood quantum of African blood. I can. I’m 8 percent African American, which means that I have a great grandparent who is Black.”

Refining the point, Arana said, “it’s not a binary thing. It’s a colorism, if you will, more than it is a racism.

“This is very much a part of my family, where you suddenly have a Black baby be born or a Chinese Asian-looking baby be born. . . .

“This very strong sense of colorism. The whole business of whitening the races is something that has come, you know, furiously down the generations from the colonial days. And still today, there is this sense that if you are slightly lighter you are better off. . . .

“The ethnicity that most intermarries in this country, in the United States of America, is the Latino. Because we’ve been doing it for 500 years and we do it here.”

Twenty-six people were in person at the Roundtable at Syracuse University’s Washington, D.C., campus, while another 27 were on Zoom. They were welcomed by Beverly Kirk, director of Washington programs, and Margaret Talev, director of the Syracuse University Institute for Democracy, Journalism and Citizenship.

“So when you talk about race relations, it’s a very, very different quantity for us. Very different. . . .”

Roebuck said, “Hispanic migrants that come to the United States suffer a high level of frustration. Because in their particular country, they were considered white.

“And now they are in the United States. . . . So many of these individuals may require a lot of psychological help to adjust themselves . . . .”

Moreover, as Arana said, in the old country, they were classified by nationality. “We come to this country, we’re all called Latinos, we’re all called Hispanics for the first time in our lives, because we were, you know, Mexican Americans or Salvadoran-Americans or or Cuban Americans . . . we were not Hispanics or Latinos. And now we are forced into that group.”

Afro-Latinos might be the exception. In fact, Arana said, during slavery, “more than 10 million, almost 11 million, all went to Latin American countries in the Caribbean. And to the United States, what, 350,000 only came to the United States. So we are very, very infused with [the] African American population.”

Added Roebuck, “There is sort of a conspiracy of attempting to deny the Afro-Latino presence, because many institutions or organizations, etc., are pushing what I call genetic purity. Let us be clear that all of the Spanish-speaking countries express a high level of racism. And when they come here, they can’t express it openly, but that particular cancer and sickness is there.”

“When you say that [Latinos] voted for Trump, exclude Afro-Latinos,” he continued. “Because many of us did not engage in that craziness.”

The Miami Herald’s Latham said that Trump found a way to exploit divisions among Latinos and African Americans.

“Trump’s campaign kind of locked in on that division,” said Latham. “You know, Democrats kind of use the ‘people of color’ as a unifying term. And Trump, I think, kind of exposed that that’s really kind of like a fallacy … I don’t believe that everybody looks at Black and Latino voters as kind of this unifying force. I think in theory, it sounds great. But when I talk to people in South Florida, I think it’s very much divided.”

According to Latham, some Latin-origin voters said, “ ‘I’m going to vote off of my conservative interest,’ but now they realize somebody in their household might be married to a Venezuelan, their cousin could have Venezuelan or Nicaraguan ties and the fact that they’re going to get deported, it hits home a little differently . . . . feel like now that they’re going to kind of see how they voted directly impacts them. . . . And I think we [the media] can do a much better job of peeling back the layers because this is a very complicated issue.”

Latham was talking especially about Cuban Americans, who have made an economic impact in Florida and nationally, from Secretary of State Marco Rubio to musician Gloria Estefan.

Like Black Americans, those of Latin origins complain of being misunderstood and, too often, considered monolithic.

“Much like we had conversations in the past with white women voters voting against their self-interest, I think that’s going to be the same conversation we have for Latino voters in 2025 and beyond,” Latham said.

Podesta and Arana cited the wars of independence in Latin America as, Podesta said, “the one . . . point where we might have come together as a unified group, Latinos, whatever color we are. “And what happened in the wars of independence is that the white elites took over, right over from the Spanish and they promoted the same hierarchy that was there before.”

The Roundtable audience, both in person and on Zoom, peppered the panelists with questions and comments.

Journalist E.R. Shipp (pictured), who teaches at Morgan State University, said journalists should be better informed — “educating ourselves so that we don’t fall so easily into certain kinds of traps. . . . Only recently did I really start thinking about some of these issues we’re raising and how these various ethnic and even tribal differences exist out there.

Journalist E.R. Shipp (pictured), who teaches at Morgan State University, said journalists should be better informed — “educating ourselves so that we don’t fall so easily into certain kinds of traps. . . . Only recently did I really start thinking about some of these issues we’re raising and how these various ethnic and even tribal differences exist out there.

“So that’s what we can do as journalists. . . . do a better job of educating ourselves so we can produce better stories, and then we’ll leave it to the activists to do some of the other things that need to be done.”

In the book, “Racial Innocence: Unmasking Latino Anti-Black Bias and the Struggle for Equality,” Tanya Kateri Hernández, a law professor at Fordham University, said the family is the scene of the initial anti-Black crime.

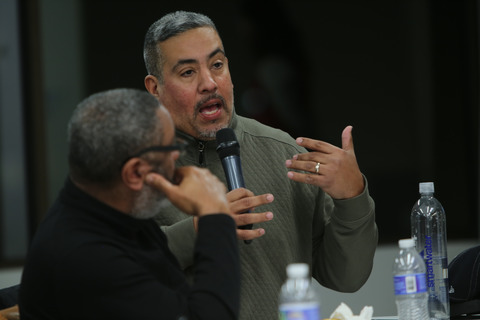

“I know that was true in my household,” Joseph Torres (pictured, with Sowande Tichawonna), senior adviser at the advocacy group Free Press, said from his front-row seat at Newhouse D.C.

“I know that was true in my household,” Joseph Torres (pictured, with Sowande Tichawonna), senior adviser at the advocacy group Free Press, said from his front-row seat at Newhouse D.C.

Family members would give such advice as “stay out of the sun because you’ll get darker.”

Torres introduced the issue of Spanish language media responsibility. “Our own media . . . we’re not addressing race in hierarchy at all.”

Unity is a challenge, Arana said.

“We do our best when we try to find our common experiences,” said the journalist and author. “And I think, you know, at this point in time that very thing is being tested. Not just for Latinos, not just for Latino relations, but generally.

“And I think if we could come to some sort of sense that even . . . with these very vastly different histories that we have — Latinos, African Americans, Anglo-Americans — that there is some sense I don’t see this being covered in the media at all. I don’t see the actual tensions that we are dealing with right now.”

John Yearwood, editorial director for diversity and culture at Politico and a former board member of the Vienna-based International Press Institute, said a good story can be had with a look at Francia Márquez (pictured), the first Black vice president of Colombia, and the second woman. She says she has endured racial abuse while in office.

John Yearwood, editorial director for diversity and culture at Politico and a former board member of the Vienna-based International Press Institute, said a good story can be had with a look at Francia Márquez (pictured), the first Black vice president of Colombia, and the second woman. She says she has endured racial abuse while in office.

As Podesta recounted, when Colombia’s president this year criticized some of the cabinet members, including her, “she came out afterwards and said, ‘You know, ever since I took over this ministry, I’ve been pilloried, I’ve been abused, I’ve been called every name in the book. I bet you, the ministry is only a year plus a few months old. So I bet you if some white guy or some mestizo from the elite had started this ministry, everybody would be saying, well, what a beast he is you can do it.’ “

Roebuck, the Puerto Rican-born activist, said Afro-Latinos in the United States can help mend any divide. First, he said, white Latinos can start by talking with Afro-Latinos, who can then serve as a bridge to African Americans.

In addition, he said, journalists must assume more responsibility to cover Latin-origin Latinos, be they white or Afro-Latinos. Accuracy is key. Journalists must report the full story.

“The role of the journalist needs to be redefined,” he said. “Especially under this special current presidential dictatorship. What is it that you’re going to do?”

Joe Davidson (pictured), columnist at The Washington Post, politely took issue with redefining the journalists’ role.

Joe Davidson (pictured), columnist at The Washington Post, politely took issue with redefining the journalists’ role.

“We can investigate. We can report; we can expose. Without necessarily labeling ourselves as an advocate,” said Davidson.

“And so you can report, you know, you can report honestly. . . . It’s a matter of your journalism exposing everything that needs to be closed or to the extent that you can. …

“The point is that you report the truth about the way this country deals with Black people and Latino people. You don’t have to be an advocate. You just have to be a very aggressive journalist.”

Marcia Davis is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist.

- Pam Avila, USA Today: 13 books to break down the immigration debate amid Trump’s return to power (Nov. 21, 2024, updated June 8)

- Mary Bruce, ABC News: Obama, Shakira Join Forces at Colombian Cultural Event (April 16, 2012)

- Ilia Calderón, Atria Books: My Time to Speak: Reclaiming Ancestry and Confronting Race (book by “the first Afro-Latina to anchor a high-profile newscast for a major Hispanic broadcast network in the United States.”) ( Aug. 4, 2020)

- Jasmyne A. Cannick, Black Press USA: FAFO Ain’t a Forcefield: Why Black Silence on Immigration Won’t Save Us (June 10)

- Adrian Carrasquillo, The Bulwark: Exclusive: Trump’s Losing the Latino Voters He Won in ’24 (May 16)

- Geraldo Cadava, the New Yorker: What America Means to Latin Americans (April 23)

- Jerel Ezell. Politico Magazine: Democrats: It’s Time to Retire the Term ‘People of Color’ Democrats’ multiracial coalition is in tatters. Mending it requires a new way of thinking about race and voting. (Feb. 21)

- Henry Louis Gates Jr., PBS: Black in Latin America (2011 series)

- Lelia Gowland, Forbes: How Your Racial And Gender Identities Can Overlap And Affect Your Career (June 27, 2018)

- Human Rights Watch: Africans and People of African Descent Call on Europe to Reckon with Their Colonial Legacies (Nov. 18, 2024)

- Institute on Race, Equality and Human Rights: In Cuba, Extreme Poverty Mainly Affects People of African Descent on the Island (Oct. 30, 2024)

- Megan Janetsky, Associated Press: Afro-Mexican communities devastated by Hurricane Erick call for emergency aid

- Journal-isms: Colorism a Troublesome Relic Affecting Newsrooms (July 15, 2023) (scroll down)

- Journal-isms: Worldwide, Do Media Have a Racism Problem? (Aug. 10, 2021)

- Journal-isms: Race, Colorism on Latino Journalists’ Agenda (July 18, 2021)

- Journal-isms: The Black Press to Our South (Oct. 10, 2022)

- Maulana Karenga, Los Angeles Sentinel: Black Interests in Resisting ICE Raids: Defending Black Immigrants, Others and Ourselves

- National Association of Hispanic Journalists: Afro-Latino Task Force

- John Nichols, The Nation: Democrats Should Listen to What Chuck Rocha’s Saying About Their Party (Dec. 6, 2024)

- Eugene Robinson, Free Press: Coal to Cream: A Black Man’s Journey Beyond Color to an Affirmation of Race (1999 book written after Robinson covered Brazil for the Washington Post)

- Edward Rueda, NBC Latino: They’re uncovering their ancestry — and questioning their families’ racial narratives (Sept. 29, 2024)

- Nour Saudi, Latino USA: Hombre: Understanding Latino Men ft. Chuck Rocha (Jan. 12)

- Lauren Villagran, USA Today: He voted for Trump. Now his wife sits in an ICE detention center.

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- “Black Journalists Will Figure in Jimmy Carter’s Legacy” on Sirius XM’s “Urban View Mornings.” (video) (Jan. 3, 2025)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World