Pulitzer Winner Reports on Roots of Today’s Racism

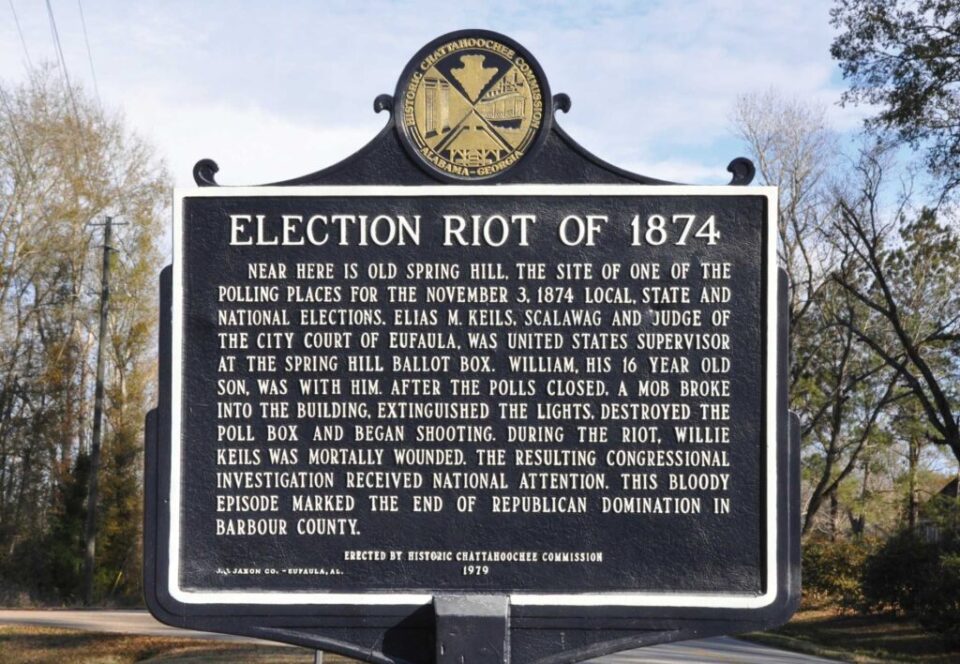

Homepage photo: A historical marker in Barbour County, Ala., erected in 1979, describes the 1874 Eufaula Massacre as a “riot.” (Credit: Jonathan Gibson/Equal Justice Initiative)

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

Pulitzer Winner Reports on Roots of Today’s Racism

- Mike Cason, AL.com: Supreme Court rules Alabama congressional map most likely violates Voting Rights Act

By Nichelle Smith

Kyle Whitmire, winner of the 2023 Pulitzer Prize in commentary, once wondered how much time he had left in the journalism business.

As the state political columnist at ALcom, he’d covered his share of scandals and scandalous lawmakers in Alabama. But Whitmire wanted to do something more meaningful.

A chance perusal of a list of race massacre sites revealed to him a little-known Reconstruction-era story: The Eufaula Election Massacre of 1874. Eufaula is a small town in southeast Alabama along the Chattahoochee River. It is known for its well-kept antebellum mansions and its memorials to everything from the Civil War to a fish named Leroy Brown. But nothing marks the intersection where on Nov. 3, 1874, seven to 10 Black men were killed and at least 80 injured when a white mob opened fire on hundreds of Black voters.

“I said, what the heck happened there?” Whitmire recalled. He intended to write only a few paragraphs about it. But the juxtaposition of this horrific story with the town’s nostalgia for an old Southern way of life inspired him to launch a series of columns examining how Alabama’s Confederate legacy haunts the state and its politics today.

In May, Whitmire (pictured) won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, “For measured and persuasive columns that document how Alabama’s Confederate heritage still colors the present with racism and exclusion, told through tours of its first capital, its mansions and monuments – and through the history that has been omitted.” Later in the month, the columnist joined others on a Journal-isms Roundtable Zoom to elaborate.

In May, Whitmire (pictured) won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, “For measured and persuasive columns that document how Alabama’s Confederate heritage still colors the present with racism and exclusion, told through tours of its first capital, its mansions and monuments – and through the history that has been omitted.” Later in the month, the columnist joined others on a Journal-isms Roundtable Zoom to elaborate.

Mainstream civil rights history lessons usually center on Birmingham, Montgomery and Selma, Alabama — landmarks made infamous because of the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Whitmire’s work centered on the roots of the movement nearly 100 years earlier: Reconstruction. Historians say this decade of U.S. history, from 1865 to roughly 1877, is largely ignored. It’s an important area for journalists to study given the “anti-woke” legislation enacted by lawmakers in Southern states, most visibly in Florida.

“This series,” Whitmire told the Roundtable, “as we tried to make very clear, was not about Alabama’s past.

“It is about Alabama’s present. It is about how we got to where we are right now. And all the things that we have not reckoned with. All the lies that still continue to be told in textbooks, in classrooms . . . the sort of things that we are seeing today, with people going into schools and trying to limit and restrict what is taught there, have happened before.”

In the Zoom chat room, journalist Roger Witherspoon asked, using lower-case letters, “is the current republican party with its open embrace of racism fostering those attitudes among Ala legislators?”

Whitmire responded, “It’s a racism much more deeply based in ignorance and indifference than outright hatred, I believe. There are GOP lawmakers who believe they are doing the right things for the right reasons, “but, at the same time, are not interested in having meaningful conversations about it with their Black colleagues.”

Thirty-six journalists joined the May 21 Roundtable by Zoom, with another 24 in person at the Washington bureau of The Wall Street Journal, roomier than it might be on a day other than Sunday.

They were there to hear from this year’s Pulitzer winners, journalists examining race and class strongly represented.

Toluse Olorunnipa (pictured), White House bureau chief for The Washington Post, was there. He and Post colleague Robert Samuels, now with the New Yorker, won the Pulitzer in general nonfiction for “His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” So was Ron Nixon, a Black journalist who is the Associated Press’ vice president of news, investigations, enterprise and initiatives. He helped guide the team that won the Pulitzer for public service for coverage of last year’s Russian attack on Mariupol, Ukraine.

Toluse Olorunnipa (pictured), White House bureau chief for The Washington Post, was there. He and Post colleague Robert Samuels, now with the New Yorker, won the Pulitzer in general nonfiction for “His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” So was Ron Nixon, a Black journalist who is the Associated Press’ vice president of news, investigations, enterprise and initiatives. He helped guide the team that won the Pulitzer for public service for coverage of last year’s Russian attack on Mariupol, Ukraine.

In addition, the group heard from Merrill Brown (pictured), editorial director at G/O Media, who will be hiring the next editor of The Root.com, and Hank Klibanoff, with an update on his Civil Rights Cold Case project.

In addition, the group heard from Merrill Brown (pictured), editorial director at G/O Media, who will be hiring the next editor of The Root.com, and Hank Klibanoff, with an update on his Civil Rights Cold Case project.

Brown, who supervises 10 websites, said “The Root is particularly important to me, quite frankly, because of its history, the legacy of people who have worked there, the ups and downs it’s had through multiple ownership situations/circumstances, and because of how critically important its mission is. And its mission is to cover a part of American life that is not always well-covered [12:00 in video].

“Its mission is to try to look under cracks where much of journalism doesn’t necessarily get to. Its mission is to cover culture in ways that some publications do rather well, but not that many; and it’s in a category where I think there’s lots of editorial opportunity.” The next Root editor also should have “the right journalism context, especially in this moment, and [an understanding of] the business model challenges that all of us on this call are familiar with. . . .”

Klibanoff (pictured) and law professor Margaret Burnham are co-chairs of the President Biden-appointed and 2019 Senate-confirmed Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board.

Klibanoff (pictured) and law professor Margaret Burnham are co-chairs of the President Biden-appointed and 2019 Senate-confirmed Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board.

“We were created to overcome longstanding problems that journalists, scholars and families have had accessing government-held records on civil rights cold cases. . . . We’re starting the process of hiring ten people — a chief of staff, an attorney, an executive assistant, a communications specialist and six researchers,” Klibanoff messaged, saying he was looking for candidates.

Pulitzer administrator Marjorie Miller (pictured) said she followed through on her organization’s commitment to take the Pulitzers on the road to demystify the awards among the public, and responded to criticism from editorial cartoonists about their category being absorbed into a larger one called “Illustrated, Commentary Reporting and Commentary.”

Pulitzer administrator Marjorie Miller (pictured) said she followed through on her organization’s commitment to take the Pulitzers on the road to demystify the awards among the public, and responded to criticism from editorial cartoonists about their category being absorbed into a larger one called “Illustrated, Commentary Reporting and Commentary.”

Miller said that decision was made before she arrived last year, but added, “Part of the issue was that the board felt that as the editorial cartoonist population diminished in the country or didn’t grow. . . . It was the same people entering and winning, for the same kind of work over and over.” And they wanted to expand the pool of people who were doing that work also. . . . We invited a lot of cartoonists to be on the jury,” although the prize ultimately went to illustrator Mona Chalabi, contributor to The New York Times, not to an editorial cartoonist.

For “Pulitzers on the Road,” Corey Johnson of ProPublica, who in 2022 won an investigative Pulitzer with two colleagues at the Tampa Bay (Fla.) Times, spoke to about 125 people in person and 400 virtually in Madison, Wis., last year. Johnson and his Tampa Bay colleagues wrote a series on how the last remaining lead factory in Florida was secretly and knowingly poisoning hundreds of workers and the surrounding community.

“We just got into the things that a lot of a lot of readers don’t get a chance to see about the journalistic process,” Johnson said. For the Madison panel, he included the wife of one of the poisoned victims as well as a government regulator who spoke about the actions taken in the wake of the reporting. “They took real tangible actions to correct this stuff as a result of the journalism. And so for people who are kind of in this ‘fake news’ energy, or ‘we don’t want to fool with journalists’ or ‘enemies of the people’, it was just a real tangible way, in plain language, to make what we do real.”

Whitmire’s columns for ALcom took readers on a historical tour of the places in which Alabamians take great pride, such as its museums, monuments and state capitol in Montgomery. In writing about Eufaula, Whitmire conferred often with historian Jefferson Cowie, who won the 2023 Pulitzer in history for “Freedom’s Dominion: A Saga of White Resistance to Federal Power” about pushback against change in Barbour County, where Eufaula is located and where former Gov. George Wallace was born.

“I really wanted to get to the heart of why this state that I’ve grown up in is so broken,” Whitmire said.

Kidada Williams, Wayne State University historian and author of “I Saw Death Coming: A History of Terror and Survival in the War Against Reconstruction,” noted in a recent lecture that Reconstruction is generally categorized as a failure with the unspoken implication that Black people were the ones who had failed to make the most of the rights and freedom they had been given.

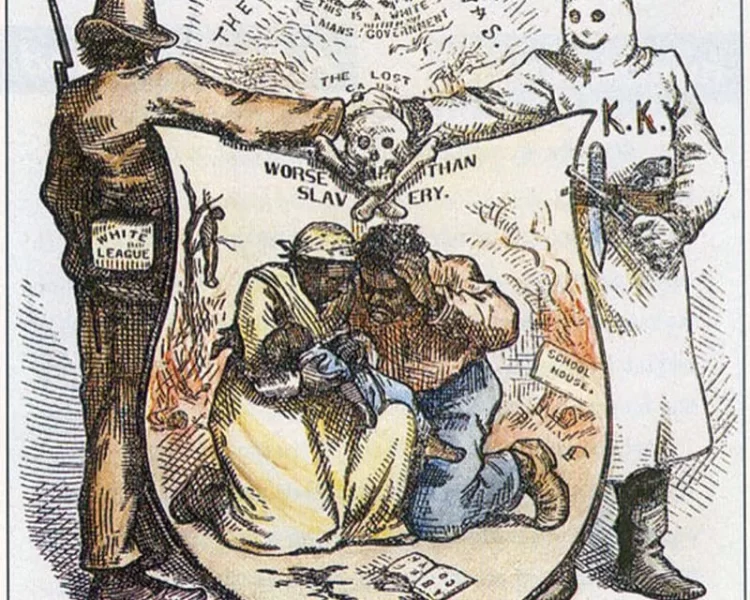

Little attention, Williams said, is given to the growth of the Ku Klux Klan and such groups as the White League, which terrorized and killed any of the formerly enslaved who showed any attempt to build new lives.

“Reconstruction didn’t fail,” Williams said. “White Southerners violently overthrew it and white Northerners and Westerners essentially let them.”

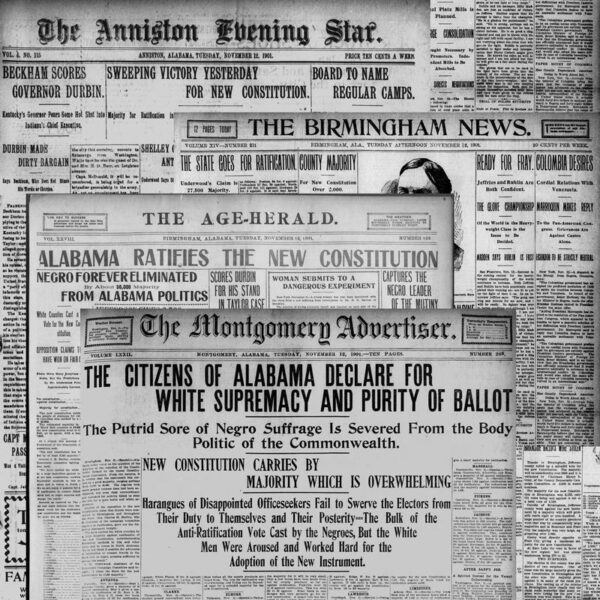

Also ignored is the creation of laws and constitutions throughout the South designed to strip away the rights of the formerly enslaved, including the right to vote. After Mississippi passed its Reconstruction rollback constitution, which in 1890 established poll taxes and literacy tests, other Southern states followed. Even today, they grapple with eradicating racist and sexist language.

In Louisiana, NOLA.com columnist Will Sutton wrote in May that state Rep. Edmond Jordan’s efforts to update 1898 constitutional language to explicitly abolish slavery had stalled amid heated debate: Some white legislators demand changes that would reaffirm the use of prison labor, while some Black legislators say such changes are unnecessary and simply a wedge to dismantle the bill.

“The Alabama Constitution of 1901 was written to disfranchise Black Alabamians,” Whitmire said. Planters and plantation owners “wrote the source code for Alabama to benefit themselves and to take power away from not just Black Alabamians, but poor white Alabamians too,” he said, because they feared a populist uprising if former slaves and poor whites began working together to better their economic situations. Though race- and gender-targeting language has been removed over the years, with the most recent changes in 2022, “it’s still this nasty, racist document,” Whitmire said.

A state away in Florida, governor-turned-presidential candidate Ron DeSantis is banning diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and curbing mentions of systemic racism in the teaching of Black history.

The Washington Post noted in February that 18 states had restricted what can be taught about race, with the most recent legislative actions taken in 2021 and after.

In August, the National Association of Black Journalists convention will be held in Birmingham as the city marks 60 years since pivotal events in the civil rights movement – the Children’s Crusade, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the arrest of King and his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” — forced the nation to confront change.

In August, the National Association of Black Journalists convention will be held in Birmingham as the city marks 60 years since pivotal events in the civil rights movement – the Children’s Crusade, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, the arrest of King and his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” — forced the nation to confront change.

“Those of you who are planning on being there come find me,” Whitmire told the group. “I’ll be there. And maybe I’ll change a few minds about Alabama.”

Also at the session:

- Olorunnipa said that though his book covers Floyd’s life as a contemporary Black man, it is also rooted in Reconstruction. Floyd’s great-great-grandfather was born enslaved, but by 1901, he was able to amass wealth and some 500 acres of land that eventually slipped away due to racist systems. Olorunnipa and Samuels looked at the impact of the disappearance of generational wealth on the family and the arc of Floyd’s life.

“If he hadn’t died on camera, maybe none of us would ever know about him, but we tried to restore some of that humanity and restore the importance of his story,” Olorunnipa said.

- James V. Grimaldi, who hosted the Roundtable and was part of the team that won the investigative reporting Pulitzer for holding financial officials to account for ethical violations, described the accountability reporting that went into the winning effort. After Grimaldi’s description, Miller was asked whether only big news operations can win a Pulitzer. Not necessarily, said Miller. “You don’t have to be a big news organization. but you do have to have some resources because the journalists need to have time to do the work, and that’s the perpetual struggle, I think.” She added that she was happy to see a diverse group of news organizations represented in awards this year, including regional newspapers, local news outlets like AL.com and newer digital media.

Associated Press video journalist Mstyslav Chernov covered the first 20 days of the Russian invasion of the Ukrainian city of Mariupol. His experience is documented in “20 Days in Mariupol,” a joint project between the A.P. and PBS “Frontline,” which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival. (Credit: Associated Press/YouTube)

- Nixon told a chilling “how we got that story” in documenting the siege by Russian troops last year of the Ukrainian city of Mariupol, reporting while very often under assault, after all other news organizations had pulled out. [01:15:02.000 in the video]

The siege, which lasted more than two weeks, included smuggling out gigabytes of information past Russians by storing the data in a tampon, and journalists disguising themselves in medical scrubs given them by Ukrainian hospital workers.

Nixon began with a shout-out to two women of color who were instrumental in the project, Mary Rajkumar, international investigations editor, originally from Singapore, and Jeannie Ohm, an Asian American who is senior producer for investigations.

“In my 35 years of doing this, this is one of the things I’m most proud to be associated with,” Nixon said of the coverage, “because again, you know, everybody, Journal, Times, Post, everybody [was there] to cover this, right?

“But we just felt like we needed to really go deep into what was happening in Mariupol.”

- Mike Cason, AL.com: Supreme Court rules Alabama congressional map most likely violates Voting Rights Act

- Roy S. Johnson, AL.com: No red-flag law or Medicaid expansion; label 2023 Alabama legislative session ‘failing’

- Journal-isms: Tell It! Report the Story of Systemic Racism — It’s a Must, Say George Floyd Biographers (June 18, 2022)

- Journal-isms: Why Journalists Really Do Matter — To Regain Trust, Pulitzers May Go on the Road (May 26, 2022)

- William C. Rhoden, Andscape: The NBA’s Florida conundrum — Black players see what is happening in the state and must find a way to express their disapproval

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)