It’s a Must, Say George Floyd Biographers

Originally published June 18, 2022

Homepage photo: George Floyd statue in Newark, N.J. (photo credit: city of Newark)

Journal-isms Roundtable photos by Sharon Farmer, sfphotoworks

Support Journal-isms

A statue of George Floyd weighing nearly 700 pounds was unveiled in Newark, N.J. on June 16, 2021, just before Juneteenth. (Credit: City of Newark)

It’s a Must, Say George Floyd Biographers

On the “PBS NewsHour” Friday, host Amna Nawaz asked Washington Post associate editor Jonathan Capehart how he was reflecting on the meaning of Juneteenth, in its second year as a federal holiday.

“Well, I’m reflecting on the fact that there are school districts and states that would make it difficult to even teach what Juneteenth is about,” Capehart said, “simply because some parents [are] offended that the word ‘slavery’ is used, that people were enslaved and worked for free and were tortured and all sorts of other things in the creation and the building of this country.

“We just saw in Buffalo African Americans targeted by someone who was a believer in the Great Replacement conspiracy. Juneteenth gives us an opportunity to talk about this nation’s foundational wound that we still refuse to talk about, that we still refuse to confront.

“And so we’re in a moment in this country where Juneteenth, if a lot of these folks get their way, very well just might be a marker on the calendar with no explanation about what it means and why it’s important that we commemorate that holiday.”

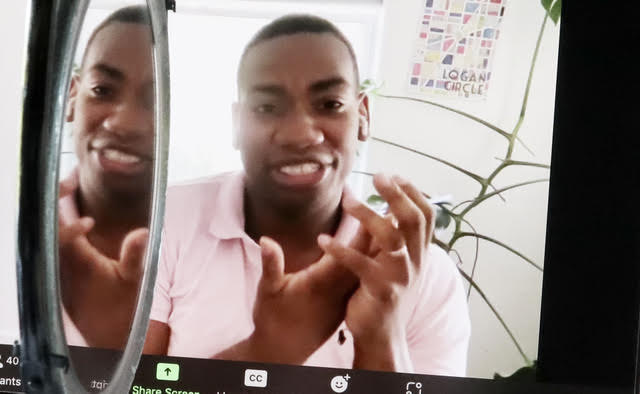

Earlier in the month, Capehart’s newsroom colleagues Robert Samuels (pictured) and Toluse

Olorunnipa (pictured, below) said with determination that journalists have a responsibility to explain

that history, adding that they had attempted to do just that in relating the story of George Floyd.

Juneteenth, celebrated Sunday, is intended to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States. Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was murdered by a white policeman in Minneapolis in 2020, prompting what was called a “racial reckoning,” however short-lived. Juneteenth and the Floyd killing are part of the same timeline.

Juneteenth, celebrated Sunday, is intended to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States. Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was murdered by a white policeman in Minneapolis in 2020, prompting what was called a “racial reckoning,” however short-lived. Juneteenth and the Floyd killing are part of the same timeline.

Today, “there is this backlash,” Olorunnipa told the Journal-isms Roundtable on June 5, as he appeared by Zoom with Samuels, fellow co-author of “His Name Is George Floyd.”

“There is this sense that maybe, you know, we talk too much about race or George Floyd’s death . . . but i think our role as journalists is to keep pushing forward, keep enlightening people, keep providing information and hoping that the more light is spread on an issue, the more information is put out there, the more people are able to grapple with these ideas, the more change happens over time, even though there are, you know, fits and starts. . . . “

“His Name Is George Floyd” is not just about Floyd’s death, but his life. Samuels said the authors wanted to illustrate “how systemic racism plays out in a real way. . . . The chance to tell this story and to talk about so many systemic failures really meant something to me.”

Said Olorunnipa, known as “Tolu,” “We as journalists have a role to play in not just letting the conversation move on . . . people . . . are still dealing with the issues that George Floyd dealt with in his life, and I think it’s our work as journalists to make sure that those individuals, those communities get coverage and get focused and get our attention, just the same way that, you know diners . . . in the Midwest get attention focused. . . . It’s important that we cover it all.’

The reference to diners harkens to the Trump presidency, when reporters sought out white Trump supporters to explain his appeal. Olorunnipa covered the Trump White House first for Bloomberg, then for the Post.

Jennifer Kho, incoming executive editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, wrote, “Congrats, Robert and Toluse, and thanks for doing all this important work and for this inspiring insight and bringing so much humanity into this story. I love this quote from Tolu: ‘George Floyd’s story was a compelling story before he met Derek Chauvin.’ I love the question of how we can tell these important and impactful stories about people before/not only when they die.”

The June 5 Roundtable drew 40 attendees on the Zoom, and another 892 on Facebook. You can watch the Roundtable on YouTube here or in the embedded version, above.

The Post reporters were questioned by panelists:

- Natalie Hopkinson, Ph.D., associate professor at Howard University, whose books include “Deconstructing Tyrone: A New Look at Black Masculinity in the Hip-Hop Generation,” co-authored with Natalie Y. Moore.

- Caroline Brewer, who has a new children’s book, “Say Their Names,” due Aug. 22. “It’s one of the few post-George Floyd books published for children, and one of even fewer written from a child’s perspective,” said Brewer.

- Ken Lemon, a reporter with WSOC-TV, Charlotte, N.C., vice president – broadcast of the National Association of Black Journalists and chair of the NABJ Black Male Media Project. Last year, the project reflected on how Floyd’s death “ignited renewed pleas for equity and a reawakening of social justice across a broad spectrum including the field of journalism.”

The Roundtable also toasted Terence Samuel, who last month was named vice president and executive editor at NPR, and Jennifer Kho (pictured), the new executive editor of the Chicago Sun-Times and the first woman and person of color in the job. (She’s of Indonesian background.)

Reminded of NPR’s efforts toward diversity, Samuel said of his own promotion, “May there be more progress to come.”

Kho said she would aim at “telling more stories beyond like crime, corruption,” and focus on “all the people who are trying to do great things as well. Trying to have more of a balance, more of a mix, and to reflect and to tell more stories that really matter to different parts of the community that haven’t really been included in the past.”

Attendees asked co-authors Samuels and Olorunnipa whether they could watch the video of Floyd’s death without being emotionally affected and whether, in their more than 400 interviews, they had observations on how the tragedy affected children in and out of the Floyd circle. The last question was posed particularly in light of suggestions that the bodies killed in the May 24 mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas, be displayed publicly to induce public revulsion, as did the beaten, swollen body of Emmett Till in 1955.

The Uvalde shooting claimed the lives of 19 children and two adults. An AR-15 rifle so mutilated most of the bodies that only DNA tests and fragments of clothing could identify them.

“I think mainstream culture often demands people of color show unambiguous examples of our oppression before they believe it happened,” said Eric Deggans, NPR television critic.

Samuels said he helped cover the December 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., where 20 small children and six adults died. He replied, “Journalism needs to rethink how mass shootings are covered. . . . After covering the Alton Sterling murder, I was done. I had no interest in doing it all over any more.”

Olorunnipa said, “I actually didn’t watch the [Floyd] video until I had to sit down and grapple with it in order to try to write that part of the book, in part because I knew enough about these experiences, these killings, to kind of get a sense for what happened from reading about it. . . .

“There is a certain trauma in watching Black death over and over and over again at the hands of a state agent and . . . whenever there’s a chance to watch . . . the latest killing I tend to, you know, turn away or scroll away . . . the actual process of going through watching someone lose their life on camera I think is something that as journalists we have to grapple with. Especially in the TV world, he said, where those images are “part of the story, it’s part of the power of the story.”

It’s an issue even in radio, NPR’s Samuel (pictured) said in response to a question.

“The discussion of how to portray trauma and death . . . takes different forms but the question is always the same,” he said. “Are we serving the audience? Are we re-traumatizing people? And are we shortchanging the story? . . . The questions get more and more urgent every time we have this.”

Samuel also said, “In some ways when you hear it without seeing it, it’s at least as gripping, and if you’ve seen it and then you hear it, you know what it is, so, yeah, we debate this all the time. The question now is, it is part of the story, it’s a powerful part of the story. Do we need . . . years later to be retelling it in the same way? And the answer is clearly no. But that is a powerful piece of life-changing tape and it’s hard to get around not using it.”

The authors did not mention Juneteenth, but they did note the importance of recognizing history as the antecedent to today’s issues.

“One of the people in the chat talked about the historical part of the book where we go back into George Floyd’s ancestry,” Olurunnipa said. “You know, it’s important for us to relive and tell those stories because they get lost to history so easily. People say slavery and sharecropping was such a long time ago and they can’t connect it to what’s happening today.

“One of the things we wanted to do in the book was . . . make that clear connection between George Floyd, who came into the world in 1973, and his ancestors who came to the world in 1820 in 1857, and all the way up and through . . . racial terror that they experienced during the time of slavery and Jim Crow impacted George Floyd in a very real way. And that’s one of the things we wanted to do in showing . . . how the American Dream plays out in different families with different perspectives. . . .

“There’s a sense of you know, let’s forget that history, let’s not talk about it, let’s not teach it, but I think as journalists it’s important for us to grapple with that history to make sure that it’s in front of people and make sure people know about it as well.”

Given that history and today’s backlashes, Samuels was asked what he made of the status of African Americans today.

“We talked to Jesse Jackson and we asked him . . . what he makes of it and he told us that you really have to consider like the long arc of history to make the case. Like, you cannot just say this happened in 2020; it’s 2022, nothing has changed. You have to look at 1619 to 2022.

Al Sharpton reminded Robert Samuels that less than a month after the March on Washington in August 1963, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke, above, white supremacists bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., killing four girls. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

“And when you look at it from that sort of larger perspective, you see things in a way that’s a bit more positive.

“And the other thing that Al Sharpton said to me that it was really important to recall was that after the March on Washington [in August 1963], the church got bombed in Birmingham [in September 1963], you had the four girls who died in the church and that it had taken nine years between Rosa Parks and the actual passing of the Civil Rights Act [in 1964].

“And so I think sometimes in the midst of it you could lose kind of the more grandiose picture about what’s happening. . . .

“The pride that we have as journalists is to be able to put things in the proper context, to be able to do all the accountability stuff and all the recognition that we need to do, in hopes that you can help to dismantle some of these systems, but fundamentally, I walked out of this feeling more hopeful about the way the country is heading than less hopeful.”

- Gillian Brockell, Kate Rabinowitz and Frank Hulley-Jones, Washington Post: Juneteenth (Interactive)

- Samantha Chery, Washington Post: Juneteenth is growing. Some Texans worry it’s losing meaning.

- Maxine Beneba Clarke, Sydney Morning Herald, Australia: ‘An absolute triumph’: This vital George Floyd biography is not to be missed (May 31)

- Editorial, Boston Globe: A joyous celebration of freedom — and a path to a reckoning.

- ESPN: ESPN Juneteenth Special Omitted: The Black Cowboy Explores Largely Unreported History

- Gary Estwick, Tennessean: America is still trying to figure out how to frame the journey of descendants of its enslaved

- Tom Foreman Jr., Associated Press: Freedom riders’ 1947 convictions vacated in North Carolina

- Okla Jones, Essence: What To Watch For Juneteenth: Shows, Documentaries And Streaming Events

- Peniel E. Joseph, New York Times: Who Was George Floyd? (May 17)

- Journal-isms: Media Version of Juneteenth’s Origin Is a Myth (June 19, 2021)

- KHOU-TV, Houston: Emancipation Park gearing up for its sold-out, two-day Juneteenth celebration (includes Houston Association of Black Journalists)

- Kimberlee Kruesi and Cheyanne Mumphrey, Associated Press: Despite push, states slow to make Juneteenth a paid holiday

- Dana McPhall and Miko Brown, Daily News, New York: The real message of Juneteenth

- News Guild: Abortion as a healthcare right and collective action (Some Guild units secure Juneteenth as contract-recognized holiday)

- Darryl Roberston, Esquire: I Was George Floyd (June 3)

- Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa, Washington Post: Telling George Floyd’s story gave us a deeper understanding of racism (May 20)

- Savannah Taylor, Ebony: Tribeca Film Festival Returns With a Juneteenth-Centric Slate of Programming (June 10)

- Texas Historical Commission: Juneteenth: Freedom Comes to Texas (video)

- Vox Communications: Vox and Capital B announce partnership for a new editorial initiative examining Juneteenth

- Washington Post: How Post journalists reported on George Floyd’s life and legacy (May 9, updated May 16)

- WNYC, New York: WNYC Studios’ Kai Wright Hosts National Juneteenth Special in Collaboration With Local Texas Public Radio Stations

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018

Page views as of Sept. 17, 2022: 442