Cartoonists of Color Work Around the Obstacles

Questionable Smokey Robinson Rant Now Animated

California enlisted Lalo Alcaraz to contribute to its health project “COVID Latino.” Alcaraz told Axios that he believes Latinos are underserved medically and educationally, adding that they are often “targeted for misinformation, and consequently have lower rates of vaccination.“

Cartoonists of Color Work Around the Obstacles

It was called historic. Inspiring. Revealing. “I felt like I was in the presence of cartoon royalty,” said one retired journalist.

“What an incredible gathering and conversation. I’ve never seen that kind of panel among comics of color ever,” said another, describing the discussion among multicultural cartoon artists — Black, white, Latino, Asian American and Native American. “As the person who tried to diversify our comics pages” at her newspaper, “I know the white gate-keeping battle is real.”

The bottom line, in another’s view, is that “despite greater acceptance, cartoonists of color are still marginalized by the white press.”

The Zoom gathering of the Journal-isms Roundtable was inspired by the National Cartoonists Society’s awarding of its highest honor, the Reuben award, to Ray Billingsley.

Why have so few cartoonists of color been able to crack that curtain? The society itself provides a clue.

Asked how many of color are in the society, the group’s president, Jason Chatfield, messaged Journal-isms Wednesday, “We do not make a practice of having members list their race, gender or sexual orientation when applying for membership to the NCS, nor do we keep a record of it. We do have a diverse and thriving membership of talented cartoonists, but we are not collecting that particular data set.

“We’re so proud of Ray for his win — and a historic one at that. Long overdue!”

By contrast, the News Leaders Association, previously the American Society of News Editors, began asking newspapers to record their newsroom diversity figures in 1978.

In the media business, you can’t fix what you don’t measure.

Some 90 people were on the Zoom call, with another 140 watching on Facebook. Still others are viewing the video on YouTube. You can watch here.

Among the highlights:

- The Roundtable took place three days after American University and Journal-isms Inc. announced a partnership that has been met with a cascade of praise and good wishes.

Sam Fulwood III, dean of the School of Communication, told the group, “We hope to be able to be the place where people will gather and have these conversations where we will expose all of this genius here with our students with our faculty, and using our multimedia capabilities to be able to have these roundtables so that they will reach from Washington to Los Angeles, from Miami to Seattle.”

- Walt Carr, at 89 the dean of the panel, said he might be ready to retire after 50 years of cartooning, primarily for the Black press.

- Rob King, on the other hand, is eyeing getting back in. King left cartooning for a career in the newsroom after he was advised that “there are too few of us in newsrooms for you to go into your office, draw your little cartoon and go home and not help anybody else, or affect anybody else.” So “I switched full time into sort of being a newsroom editor,” King told us. “I went into Sports. I was Stephen A. Smith’s boss in 1998,” at the Philadelphia Inquirer. “And that changed my career and since then I’ve gone on to do things with ESPN,” where he is senior vice president and editor-at-large, ESPN content. “That has been a lot of fun, and [I’ve done] things that you’ve seen, but I will never not be a cartoonist.”

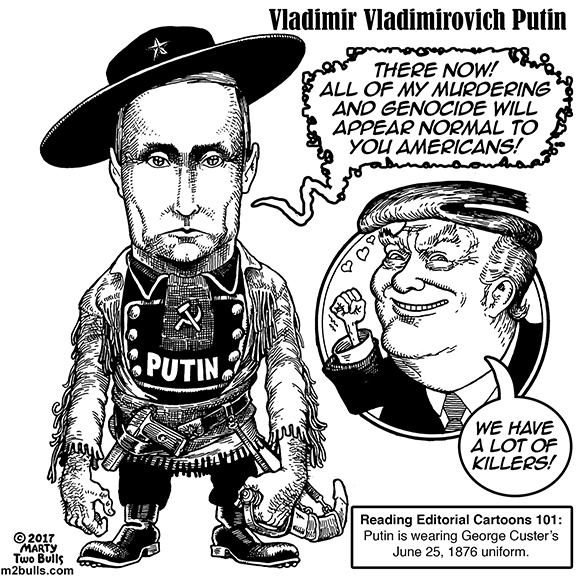

- For everyone on the panel, race or ethnic background has been a factor in their work. In South Dakota, for example, the COVID rate seems low, said Lakota cartoonist Marty Two Bulls, so much that authorities are “real, real arrogant about it.” But the pandemic is claiming older Native Americans, “so of course we lose all the culture, and all the language and the knowledge . . . with these people as well. . . . So it’s almost like a genocide,” he said.

“We have that history, you know with smallpox and whatnot. . . So I just try to keep it on the forefront.” Two Bulls’ reference was to the devastation heaped on Native Americans when Europeans introduced smallpox to their populations, a disease for which the Native people lacked immunity.

- Cartoonist-producer Joe Young disclosed that he has converted a rant by the legendary singer-songwriter Smokey Robinson against the term “African American” into an animated short that is about to make the rounds of the film festivals. (See separate item, below.)

- For some, the mission is bigger than newspapers. “I am working right now with my production company with the state of California Department of Public Health, and also Arizona State University, and doing a campaign against COVID misinformation in the Latino community, primarily in the farmworker campesino community of the Central Valley of California. . . .,” Lalo Alcaraz said. “If you want to see how my background informs my artwork, there you go.”

- A decision by the Pulitzer Prize board last year not to award a cartooning prize for the first time in 48 years still rankles. Alcaraz and Two Bulls were finalists. The cartoonists, including those who were not panelists, said the Pulitzer board has a New York bias. Other cartoonists have joined in the outrage. Last week, the Pulitzer board downgraded the editorial cartooning category into “illustrated reporters and commentators.”

- The number of cartoonists of color at newspapers is kept down by the “we already have one of those” syndrome. Barbara Brandon-Croft, whose “Where I’m Coming From” offers a Black woman’s perspective, is no longer syndicated. Her strip has been “rejected because they already had a Black strip.” Or they already had “Cathy,” about a white woman struggling with modern life. Yet they would run multiple strips about animals, Brandon-Croft said, such as ‘‘Heathcliff” and ‘”Garfield.” “I mean, come on.”

- Hector Cantu, co-creator of “Baldo,” about a Latino family, said that one newspaper that had told him, “We already run a Hispanic strip,” had additional cartoons that ran only on its website. “I looked at those and almost all of them were non-minority comic strips . . . even when they have that digital space.”

Carr wrote, “I get the B’more Sun and the Washington Post — the Sun has 22 comic strips…only one Black strip. The Post has 41 strips…only 2 Black strips.”

- Rebecca Aguilar, president of the Society of Professional Journalists, said that “I have always thought as a journalist that political cartoonists, editorial cartoonists are really just journalists” — cartoons grab attention in ways that words alone do not — and that SPJ and other journalism organizations “need to make noise for you guys.” To her first point, Josh Neufeld explained the concept of “comics journalism” — reporting a story through artwork. Comics “don’t have to always be humorous or fanciful or about superheroes or funny animals; they really can be about anything.”

- Cartoonists of color are still driven by the desire to educate. A cartoon from Angelo Lopez, a Filipino American who draws for Philippine News Today, a weekly in the Bay Area, framed attacks on Asian Americans last year in the context of historical anti-Asian violence. In Watsonville Calif., for example, mobs of up to 500 white people roamed the city and its surroundings in 1930, attacking Filipino farmworkers and their property after Filipino men were seen dancing with white women at a newly opened local dance hall.

Race was the reason Carr switched from gag cartoons to more serious fare, he said, all those years ago. “I wanted to be a voice. I wanted to point out the hypocrisy that we’ve been dealing with all these years.” Carr joined others in praising the Black press for providing outlets for that perspective, like the “Strictly for Laughs” page in Ebony magazine, which featured his cartoons and Billingsley’s.

- Despite some progress in newspapers — the “Mark Trail” comic is now drawn by Jules Rivera, who is Latina — more advances are being made in other parts of the comics industry, Cantu said. Graphic novels by cartoonists of color are in demand.

- However, the award-winning “New Kid,” a graphic novel by cartoonist Jerry Craft, based on his experiences as the new Black 12-year-old in a majority white school — became the focus of a controversy in Katy, Texas. A mother falsely claimed it represented “critical race theory,” as the public radio show “This American Life” reported.

Signe Wilkinson, retired cartoonist for the Philadelphia Daily News, took the conversation to the nuts and bolts when she asked advice for “the paler among us.” She sought observations about “how white cartoonists draw Black people.”

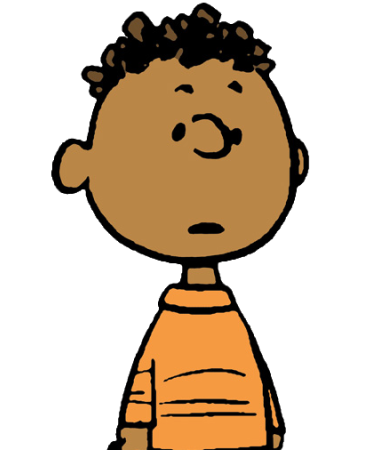

Replied Billingsley, “What I basically see from non-Blacks are almost like empty shells. Characters without personality.

“There’s a lot more into a Black character than they think. I have a favorite story with Charles Schulz. We were talking about Franklin (pictured),” Schulz’s Black character created in 1968, during the civil rights era. “We used to joke with each other a lot.

“There’s a lot more into a Black character than they think. I have a favorite story with Charles Schulz. We were talking about Franklin (pictured),” Schulz’s Black character created in 1968, during the civil rights era. “We used to joke with each other a lot.

“And he asked me what I thought of Franklin.

“And I said, ‘Well, you really haven’t given him enough personality’. And he looked at me, puzzledly. And I said, ‘Look, we know Lucy’s a loudmouth and Charlie Brown’s the loser and Schroeder plays the piano.

“What does Franklin do?

“And he just looked at me and he burst out laughing. And I know it was a little awkward silence behind that because if you’re going to do a character that is nonwhite, you have to research him a little bit.

“Give them a little bit also . . . the characteristics. Some of the hair, maybe lips. Most people feel like they’re afraid to . . . the representation of Blacks needs to be a little deeper.”

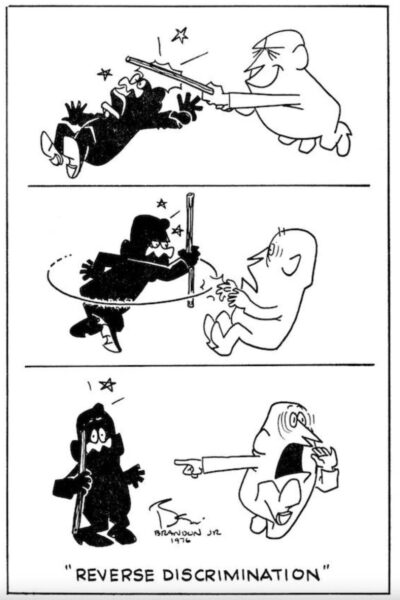

And ditch the urge to use the pen to darken skin. “You know, historically,” when “cartoonists were doing Black cartoon characters in white newspapers, they would just make us black, you know like my sweater,” Brandon-Croft said. “And it took the NAACP to make a stink about it, like ‘hey, you can’t keep doing this, this is ridiculous. . . .’ You couldn’t even distinguish women [from] men, it was just, it’s just blackface.”

Billingsley said he rarely even tries to draw white characters, “because I don’t know what it’s like to be white. I don’t know the little, little things about being white that makes a person one, so I don’t do them.”

After the session, Wilkinson said she was pleased. “It was a privilege to be with cartoonists whose work I admire and be able to hear them talk about their trials getting started. Having been told, ‘We already have a woman cartoonist’, I had a glimmer of what they’d been through,” she said.

“Usually panels on this subject rope in a few black cartoonists who have to explain things to audiences of mostly white cartoonists. I loved hearing the speakers talk so freely and with such generous humor about their work and the white world they operate in. I hope they didn’t mind my eavesdropping!”

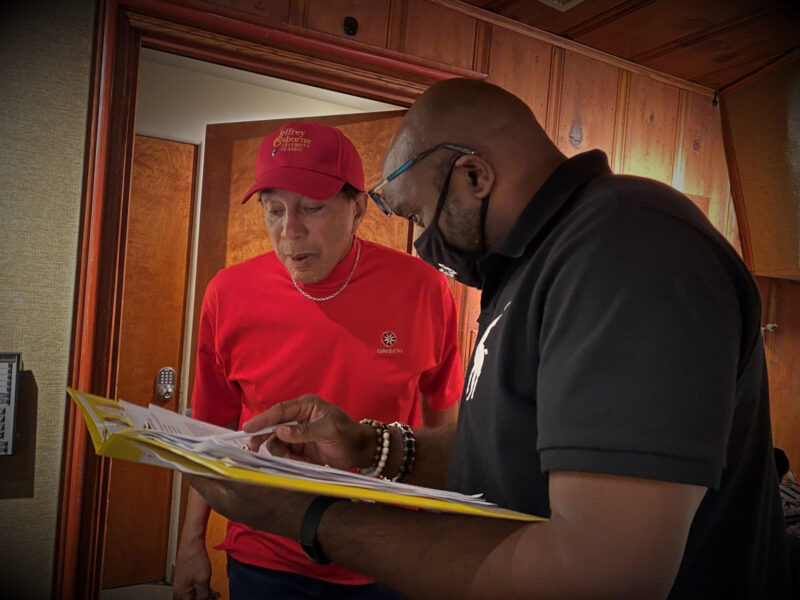

In addition to the cartoonist discussion, the Roundtable toasted Sandra M. Clark (pictured), formerly of the Philadelphia Inquirer, who is leaving public station WHYY. She has been named CEO of StoryCorps, effective in February.

In addition to the cartoonist discussion, the Roundtable toasted Sandra M. Clark (pictured), formerly of the Philadelphia Inquirer, who is leaving public station WHYY. She has been named CEO of StoryCorps, effective in February.

Clark said, “if you’re not in the NPR network, you might not know StoryCorps . . . . My goal is to really take it to, you know, to the people. . . . So I’m moving from local news for the first time in many, many years to a place where, you know, I hope we can continue to . . . forge all the stuff that we’re trying to do in journalism, but in a different, different kind of space.”

We raised a glass also to Michael Bolden (pictured), who has been named executive director and CEO of the American Press Institute (scroll down). API is “dedicated to helping news publishers navigate and adapt to organizational and industry change to sustain journalism.”

We raised a glass also to Michael Bolden (pictured), who has been named executive director and CEO of the American Press Institute (scroll down). API is “dedicated to helping news publishers navigate and adapt to organizational and industry change to sustain journalism.”

Bolden said, “We want our newsrooms to be places where people want to work, especially now when we’re experiencing the Great Resignation and so many people are questioning our institutions and what they’re doing. . . . you know I know API has been doing work to help on diversity, but diversity is not an adjunct to anything else. Diversity is part of the core, it is tied into operations. . . . I look forward to connecting with anybody who wants to join with us and helping make that change.”

We also heard from Frances Huntley-Cooper (pictured), former mayor of Fitchburg, Wis., part of a group planning a Center for Black Excellence and Culture in Madison, Wis. “Black folks are recruited for jobs here in the Madison area, or we attend the University [of Wisconsin], but we leave,” she said. “And we need to make sure people feel comfortable when they come and they have a place to assemble and gather and talk about issues and support each other from the economic leadership, youth, adults, services, all of those targets or areas would be included.”

We also heard from Frances Huntley-Cooper (pictured), former mayor of Fitchburg, Wis., part of a group planning a Center for Black Excellence and Culture in Madison, Wis. “Black folks are recruited for jobs here in the Madison area, or we attend the University [of Wisconsin], but we leave,” she said. “And we need to make sure people feel comfortable when they come and they have a place to assemble and gather and talk about issues and support each other from the economic leadership, youth, adults, services, all of those targets or areas would be included.”

It was suggested that the Center include training in journalism and news literacy, and perhaps a vehicle for storytelling.

The next day was the 70th birthday of Jim Asendio (pictured), a self-described “gleefully retired radio news broadcaster” who called into the Zoom from his new home in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

The next day was the 70th birthday of Jim Asendio (pictured), a self-described “gleefully retired radio news broadcaster” who called into the Zoom from his new home in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands.

Asendio wrote on Facebook, “It is especially important to have islands of calm, support and inspiration in times such as these. This Roundtable group is one of those islands. We share a love of communication that informs whether it be written, spoken or visual. We each strive to make today and tomorrow better. Knowing you are there is both comforting and inspiring. ❤️ to you all.”

- Sandra Bookman, WABC-TV, New York: Barbara Brandon-Croft reveals what to expect at her latest exhibit “STILL: Racism in America – A Retrospective in Cartoons” (March 30, 2020)

- Japanese American National Museum: Exhibit: Mine Okubo’s Masterpiece — The Art of Citizen 13660 (A comic journalist chronicling the Japanese American camp experience)

- Lyanne Melendez, KGO-TV, San Francisco: Political cartoonist uses storytelling to help dispel COVID misinformation in Latino community (Dec. 20)

- Norah O’Donnell, “60 Minutes,” CBS: Bridging America’s political divide with conversations, “One Small Step” at a time (Jan. 9) (Segment on Story Corps)

- Richard Prince, National Conference of Editorial Writers: Black cartoonists missing from pages. (1996)

- Yacob Reyes, Axios: Fighting COVID misinformation with cartoons (Dec. 14)

- Edward A. Rueda, NBCU Academy: Marty Two Bulls and Lalo Alcaraz didn’t win the Pulitzer. But they don’t draw for the judges. (July 1)

- Ronald Wimberly, The Nib: Lighten Up: A cartoonist reflects on the subtle racism of shifting skin tones in a Marvel comic (2015)

Questionable Smokey Robinson Rant Now Animated

You wouldn’t mistake Smokey Robinson for a scholar or a journalist who carefully checks his facts. Regardless, a rant by the legendary singer-songwriter against the term “African American” (video) has been made into an animated short that is about to make the rounds of the film festivals.

The rant dates at least to 2004 and contains errors of fact that today would be called misinformation.

Cartoonist Joe Young told the Journal-isms Roundtable Sunday that he was working on the animation project with Robinson, and later told Journal-isms that, “In February we will be scheduled to do a private screening for NBCUniversal executives.” He said they are entering the project in film festivals such as Tribeca, and that they are hoping to be on television’s “The View.”

In the rant, Robinson asserts that “every few years we get a change of name” and that he remains proudly Black and proudly American, as if “American” were not part of “African American.” Besides, he added, since humanity originated in Africa, everyone can claim African heritage. “Everybody in the Orient is an African Asian,” he said by way of example, using an “O” word that Asians have discredited, as has the Associated Press stylebook.

In one section of the rant, which has slight variations with each retelling, Robinson, who turns 82 on Feb. 19, says, “In the 1960s, when we struggled and died to be called equal and Black and we walked with pride with our heads held high and our shoulders pushed back, Black was beautiful. But I guess that wasn’t good enough, ’cause now here they come with some other stuff.

In one section of the rant, which has slight variations with each retelling, Robinson, who turns 82 on Feb. 19, says, “In the 1960s, when we struggled and died to be called equal and Black and we walked with pride with our heads held high and our shoulders pushed back, Black was beautiful. But I guess that wasn’t good enough, ’cause now here they come with some other stuff.

“Who comes up with this s— anyway? Was it one or a group of n—–s just sitting around one day, feeling a little insecure again about being called Black and decided that African American sounded a little more exotic. Well, I think you were being a little more neurotic. It’s that same mentality they got ‘Amos and Andy’ put off the air because they were embarrassed about the way the characters spoke and as a result of that, actually, a lot of wonderful Black actors ended up broke. We were just laughin’ and having fun about ourselves.

“So I say, f— you if you can’t take a joke. You didn’t see ‘The Beverly Hillbillies’ being protested by white folks. . . . How come I didn’t get a chance to vote on who I’d like to be? Who gave you the right to make that decision for me? I ain’t under your rule or in your dominion and I’m entitled to my own opinion.”

Actually, the “Amos ‘n’ Andy” sitcom was written by white writers Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll, first on radio, where whites shamelessly played the roles; “African American” exists alongside “Black”; no one issued any decree; and choice of the term had nothing to do with sounding exotic.

As reported in this space, “In 1984, the National Alliance of Black School Educators, an organization of school superintendents, named a task force on the future of black children.” They used the term ‘African American.’

“The term had been in use for at least 20 years among intellectuals, black nationalists and others, but this was believed to be the first time an organization had called for use of the term, the organization’s leaders told a reporter then. The next year, the Dallas Independent School District started using ‘African American’ along with ‘black.’

“On Dec. 19, 1988, the term truly entered the mainstream, as about 75 black leaders met in Chicago to discuss an ‘African American agenda.’ Using the term was part of a broad ‘cultural offensive,’ but the efforts of one reporter — Lillian Williams of the Chicago Sun-Times — made the so-called ‘name change’ the news story from the meeting. . . .”

In the cultural offensive, Ramona Edelin (pictured), then of the National Urban Coalition, Jesse Jackson and others decided that like other ethnicities, Black Americans could tie their identity to a land mass and reach back to pre-slavery days to African achievements as a way of inspiring Black American children to learn.

In the cultural offensive, Ramona Edelin (pictured), then of the National Urban Coalition, Jesse Jackson and others decided that like other ethnicities, Black Americans could tie their identity to a land mass and reach back to pre-slavery days to African achievements as a way of inspiring Black American children to learn.

Journal-isms asked Edelin what she made of Robinson’s speech.

She messaged, “In 1988 when I urged the leadership group convened by Rev. Jesse Jackson to consider consistently referring to ourselves as African American as a way of launching a cultural offensive as the foundation of agenda-setting, and the approach was agreed-to by our group, the designation was meant to be inclusive and to apply to all African-descended people living in the Americas.

“However, even at the very beginning, some West Indian and more recently immigrated African ethnicities within the race did not relate to the designation. We explicitly wanted to avoid the divisive ‘Blacker than thou’ hostilities that emerged when we made the change from Negro to Black, and simply said: if you find this useful, use it – if not, don’t.

“The point is the cultural offensive, the geopolitical muscle, the unity, the uplift. We did not trivialize the effort into a ‘name change debate’ as some in the white press did. When the New York Times interviewed me early in 1989, the reporter pointedly said they would not use African American until most of us were using it. It was gratifying to see the designation in the NYT within months of Rev. Jackson’s announcement. It was an idea whose time had come.

“Now that Black Lives Matter is a global brand, and now that our decades-long push for reparations has moved from the fringes to the mainstream of policy discussions, there are new implications to consider. Can we afford to speak only for the descendants of Africans who were enslaved in the United States on the one hand; and can we afford not to, on the other?”

Journal-isms also asked Zadi Zokou (pictured), a filmmaker from the Ivory Coast living in Natick, Mass., for his view. Zokou’s film, “Black N Black,” (trailer) examines Africans’ views of African Americans and vice versa.

Journal-isms also asked Zadi Zokou (pictured), a filmmaker from the Ivory Coast living in Natick, Mass., for his view. Zokou’s film, “Black N Black,” (trailer) examines Africans’ views of African Americans and vice versa.

“There is some truth in what he said,” Zokou messaged. “Refusing being called African American or not being acknowledged as African are topics that I developed in my movie.

“However, I would like to focus on what he said about Africa. For someone who has never lived . . . there, he has some pretty harsh statements about the continent and its people, and no nuance at all. I’m not going into too many details. Just a couple of things:

- “Whatever Smokey wants to call himself, his African origin is obvious and there is nothing he can do about that.

- “When an African American (or any member of the African Diaspora) genuinely acknowledges themselves as African and [has] real respect for their African origin, they don’t need any permission or validation from anyone to be and feel who they are.

“So, Smokey can prefer to be called Black, it is his choice and I respect that. But for a continental African like me who tries to bridge the gap and create a bond, I don’t think a rant like this one is very helpful.”

(Illustration by Joe Young)

- Siegfried Forster, 9th International Film Festival of the African Diaspora (Fifda): “Black N Black”, the difficult relationship between African-Americans and Africans (Sept. 7, 2019, updated Feb. 6, 2020) (Interview with Zadi Zokou)

- Taiyler Simone Mitchell, Business Insider: Joe Rogan said it’s ‘very strange’ for anyone to call themselves Black unless they’re from the ‘darkest place’ of Africa

- Christine Tamir, Pew Research Center: Key findings about Black immigrants in the U.S.

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018