Excerpt: Having to Police Your Tongue, Attire, Voice

Homepage photo: Credit Donya Collins/Indiana Daily Student

Support Journal-isms

Excerpt: Having to Police Your Tongue, Attire, Voice

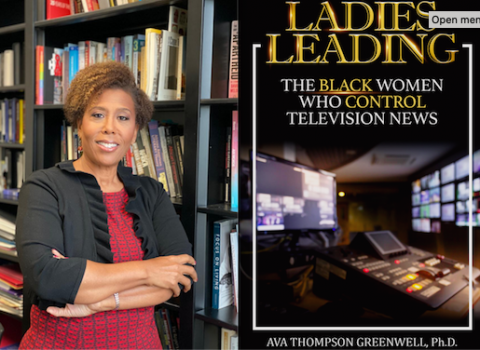

With the recent ascensions of Black women to top management roles in broadcast and print journalism, a new book by Ava Thompson Greenwell, Ph.D, “Ladies Leading: The Black Women Who Control Television News“ (Royston Publishing) assumes fresh relevance.

Greenwell teaches reporting classes at the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University. “This book brings Black women television news managers out of the shadows and accounts for both their race and gender, building a primary archive of interviews with 40 news leaders,” she writes in her introduction.

“Their stories document continued workplace bias and demonstrate the harmful inequities that exist, even when you’re the boss.”

In this excerpt from the book, as well as in the complete work, names of individuals, places and stations have been substituted with pseudonyms or generic identifiers. “I replaced most of the women’s names with flowers or gemstones. Flowers symbolized their ability to grow and bloom, despite sometimes poor nurturing conditions. Gemstones symbolized their strength and endurance to weather the storms of news,” Greenwell tells us.

This is the second of two parts of her chapter, “Suppressing Self: Hair, Body Parts and Tongue.” Part One is here.

By Ava Thompson Greenwell, Ph.D.

Participants said clothing was equally important in establishing their credibility and reputations as managers. A “politics of respectability” took over when women selected their daily work attire. Historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham detailed the concept in “Righteous Discontent” when she described the lengths to which Black Baptist women would go to make sure they dressed, spoke and acted properly.

The word “properly” aligned with white women’s definition of proper. The goal was to mimic white women, with the hope that Black womanhood would be as respected and revered as white womanhood. This often resulted in the policing of Black women’s attire, speech and behavior by other Black women and men.

During interviews with these women news managers, many said they had to dress up to be taken seriously while white men and some white women could dress down without their abilities being questioned. Violet said clothing mattered: “I’ll never forget I was in [Southville] and another producer asked me, ‘Why do you always come to work so dressed up?’ And I needed to be at work at three in the morning. I’ll never forget this. I wanted to look at her and say, ‘Because I can’t do what you do.’ I wanted to tell her that. You know it was a white woman.”

Violet said there was a double standard for Black women to dress professionally each day, while white women did not have the same burden. Violet decided that responding might make her appear angry, another stereotype of Black women, so she decided not to acknowledge the comment and to pretend as if it were never spoken. Yet, the comment remained with her for years and gnawed at her.

Tongue and Talk

Besides hair and clothing, the women were also attentive to their talk in the newsroom.

While it is common to take on a more professional persona at work, for African American women that persona sometimes felt unnatural, originating out of a history of oppression and discrimination. Fitting in with the majority sometimes leaves less room to be true to oneself. Political scientist Melissa Harris-Perry writes that American society routinely misrecognizes Black women. Even Black women sometimes misrecognize themselves. She describes the U.S. as a “crooked room” where African American women find their image distorted or off balance, making it difficult to stand upright.

Harris-Perry acknowledges that the practice of dissemblance, or hiding certain aspects of one’s being or essence, is a tool of agency for Black women to protect themselves from falling prey to the stereotypes in the “crooked room.”

Lavender said she restricted her body movements and self-censored her speech at times:

Checking it at the door, definitely. I was even aware of it when I drive into the city, I might be shaking my shoulders all the way into my music, but I’m aware when I’m getting into the city — even as big as the city is, you want to tone that down a little bit. I think that I do talk a little bit differently to my Black colleagues than my white colleagues. We’re just different with each other. The thing that is the most frustrating to me is that I always have to make the first effort, and that gets wearing. [wearying?] It really is. I find that there’s almost a veneer, that it’s almost difficult to penetrate. I think the assumption is, this is just a feeling and it’s not based on anything, but I often wonder when I come in Monday morning why is it nobody asks me what I did over the weekend like the white colleagues ask each other.

By not including her in the Monday conversations, she was both hypervisible yet invisible. She was hypervisible because she was the only Black woman among the group. She was invisible because they treated her as if she did not exist, and as if her weekend endeavors did not matter. This type of microinvalidation ignored her weekend experience and therefore devalued her social choices, devaluing her. This type of small talk is an important bonding opportunity with colleagues. When one is not included, one can wonder whether the exclusion is an intentional way of marginalizing and even restricting upward mobility. In Lavender’s case, she felt diminished and excluded in overt and simultaneously covert ways.

Other women even tended to avoid Black vernacular talk in conversations. Such actions produced a fear of making a mistake (FOMM) in terms of grammar errors and could be interpreted as incompetence. The policing of their tongue and their tone of voice were other responses to the manifestations of microaggressions. For example, a few women said they avoided using profanity or a negative tone in their conversations, even casual ones, so as not to give supervisees or their bosses a reason to label them as unprofessional.

Their avoidance, however, was a double standard. After working in newsrooms for nearly a decade, I heard profanity-laced conversations and sometimes tirades, especially from white males, on a regular basis. Often the use of such language was blamed on working in a deadline-driven environment. Despite this tradition, however, some of the women felt there was a double standard when it came to their use of profanity.

Iris was taken aback when one of her supervisees yelled at her shortly after she arrived in a new job. “I don’t know if they ever had a Black EP (executive producer). I don’t know. I just know that, within two weeks of being there, I’d been cussed out by the producer.” The producer was someone she supervised. Dahlia also remembered being cursed out by a white male supervisee. “I don’t raise my voice in the newsroom, and I tend to not use foul language in the newsroom.” Both women said if they used profanity with employees, they would be labeled unprofessional. They both agreed that if the races of the individuals had been reversed, minimally a reprimand for insubordination would have been the outcome, perhaps even grounds for dismissal.

Linnea said even when she felt profanity was warranted, she avoided it. “I didn’t like how my general manager would talk to me,” she said. “He would try to talk to you any old kind of way. I was becoming that person who would just speak out and say whatever I was thinking. I didn’t cuss or anything like that, but sometimes I didn’t always say it at the most appropriate time.”

Linnea also avoided yelling, another common practice in some newsrooms. To be clear, sometimes yelling is needed to be heard in a loud, busy, deadline-driven environment. But other times, it is unnecessary. Some of the women found yelling a sure way to be labeled “angry and abrasive.”

As the women’s testimonies have already demonstrated, not all chose to avoid the use of profanity or yelling. However, it is significant that those who chose to eliminate certain words from their vocabulary or certain tones from their voices did so because they thought the practice would reflect poorly, not just on them, but on all African American women. Whether they knew it or not, they were practicing respectability politics and dissemblance when they chose not to share their true feelings about an issue. They did not want to negatively represent their race. This type of suppression, when not practiced by peers and bosses, is a self-imposed double standard. Their racial and gender identities prevented them from being fully themselves. The discrimination lay in their perceived inability to behave as unprofessionally as other station employees.

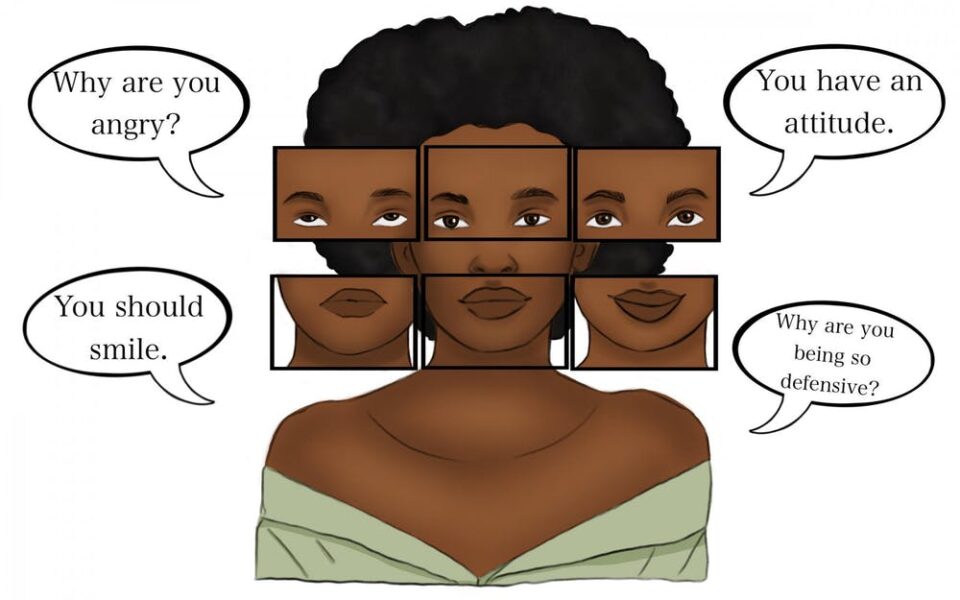

Unprofessional behavior is not the only area where the women experienced inequity. These women’s assumptions of perceived incompetency, scenarios with peers and bosses that rendered them invisible and/or unable to be heard and the suppression of their speech, hair, clothing and conversations were enough to make anyone angry. However, on top of the various microaggressions, African American women must also negotiate the “angry Black woman” stereotype.

Scholars have traced this stereotype to “Sapphire,” the loud, brash-talking Black female character of the Amos ‘n’ Andy Show that aired on the radio starting in 1928 and continued on television through the 1950s.

Although other scholars have tried to debunk this stereotype with empirical data, the idea persists that Black women are angrier or more abrasive than other women. For instance, the presence of an African American First Lady from 2009 to 2017 raised the stereotype to a new level of public discourse. The stereotype became the subject of several personal websites and news articles questioning whether former First Lady Michelle Obama warranted the label. The topic was a daily struggle for nearly all the women interviewed, who stated they tried to avoid showing anger because they did not want to be labeled “the angry Black woman,” even when they sometimes felt angry.

Lily considered “not being the angry Black woman” one of her daily pressures: “But the reality is — and I can only speak for my own personal experience – I have found that I have to work a lot harder to make people comfortable with me. I don’t get the same license to mouth off. For whatever reason, if I am angry or frustrated it comes off in a completely different way.”

To avoid being stereotyped as the angry Black woman, a few women said they often stopped to think about what they were going to say to an employee longer than they probably should have. So, in addition to double, triple and sometimes quadruple checking their work and the work of others, they spent valuable time composing themselves so they did not come off as unhinged. They knew their anger was not perceived the same way as whites in the newsroom.

This stereotype is particularly tricky to negotiate when you are an African American woman manager. When you are the boss, your job is to instruct people on what to do. Yet Black women’s roles since slavery have been largely about carrying out orders, not giving them. How can you be in charge without speaking up loudly and forcefully during assignment meetings? Some of the women recounted being told they were too “bossy” or “intimidating.” Cassia said her mother’s life lessons helped her navigate the workplace in this regard:

The key thing my mother has said to me all my life is it’s never what you say, it’s how you say it. So, somewhere in there, learning how to say what you need to say to get what you want. To politicians, it can make you a manipulator, it can make you a whole bunch of things; it can also make you successful. And so, I think that angry Black woman, that part of that is tough in the newsroom. Everybody’s angry.

Dove, on the other hand, said she had a temper and it often showed up in the newsroom in her interactions with others:

I do feel that I did, in some ways, hinder some progress because I always spoke my mind … I’ve been looked at in a certain way because they say, “Ooh, we can’t deal with Dove. She’s too strong. She’s too whatever, she’s going to speak out about some stuff.” And so, I do think I’ve paid a price for that. I did bring a different voice to the table and a different set of ideas. Did I get mad a lot sometimes? Yes. Did I lose my temper sometimes? Yes, because I felt like they didn’t appreciate what I was offering. They would go off on a story that I knew was the wrong way for them to go until finally, I guess as I got older, I got more mature and I picked my battles and understood that this is their problem, not mine, in terms of them not understanding.

Some women said “speaking up” with authority and passion could also get them labeled “angry” even when they were not. Somehow their white colleagues’ similar behavior was not perceived the same way, as Ruby explains:

The African American producer that I hired here had a rough couple of months. People were kind of attacking her ability to do her work. And so, I had to have some conversations with her, not just about the work, but not shaking her confidence. And I think she was having trouble kind of blending in and working with people. Is it because she’s Black? I don’t know. But it was touch and go, a couple of months. She’s kind of found her groove now, but I had never heard a complaint about her, until my news director said, “Well, you know, I’ve heard from some people that she can be a little abrasive.” And I’m thinking, “What is abrasive? Like what does that mean? Like is she cursing people out? Or is she being very direct in telling somebody.”

Being direct in dealing with employees was another way to get labeled as angry or intimidating. When a Black woman does not smile all the time or engage in idle chit-chat she can be labeled “too serious.” Lily’s style was to be direct because that’s how she wanted to be treated:

I remember a news director told me I need to find the softer side of myself. And I totally get you don’t want to hurt people’s feelings, but sometimes I can just be very direct. Now that doesn’t mean that I am abrasive. It just means this is what I need done, and I need it done now. And I think some people take it a different way.

A retired white male news executive, who had mentored some of the women, acknowledged that being Black and female is a delicate balance in most newsrooms:

There’s a disproportionate responsibility about being Black in a mostly white environment, in terms of how much impact you can bring, without becoming a disproportionate advocate for being African American. Frankly, it’s a very tough balance. Because what you want to do is you want to be part of the whole. You don’t want to be an angry African American journalist. You want to be constructive. You have to be part of the process. You have to move with the majority of the process, and you have to pick your spots in terms of influencing the way you conduct yourself.

The extra thought given to microaggressions, perceptions of hair, dress, tone, profanity and conversation is extra mental labor. This is all before they can think about the actual job of running a television newsroom. No wonder Black women can feel as though they are carrying an extra backpack. Some of the women said they even considered their physical stature when deciding whether and how to address a particular topic or person.

For example, Dahlia said she considered her height before she engaged in a serious conversation. “I’m usually the tallest person in the room and my mother even told me once . . . ‘By your appearance alone, it’s intimidating. So, if you walk into a room and you’re yelling and screaming, think of how that makes you look.’ ” Dahlia reported she rarely raised her voice in the newsroom, yet she had been told she was too aggressive and needed to “pull it back.”

Aggressiveness is normally a desirable characteristic of newsroom employees. Anger is not. However, “angry” could mean just challenging the way things have been done in the past, which most leaders are expected to do. This damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t dichotomy at times was frustrating for Black women news managers. Daisy once made a reporter . . . redo a story because it stereotyped African Americans. She said she felt like her colleagues thought she was angry. She said she was demonstrating excellence:

I was thinking let’s show our market what our community looks like. It wasn’t about being an angry Black woman, but I think anytime you try to raise any concern about an issue where you want to show fairness or you want to show real diversity or you want to avoid any type of stereotype then that’s immediately the way they want to paint you.

Blossom agreed that aggressiveness is encouraged in most newsrooms, but not always if you are a woman, especially a woman of African descent. “They perceived sticking up for yourself as aggression and that there’s a problem with you and they just want you to take it.” Wren explained that passion in African American women is often mischaracterized as a negative quality, “Sometimes being passionate about something is characterized as being angry. Sometimes, I think it’s a stereotype that I think female leaders must be aware of.”

Topaz agreed, indicating that she often held back to avoid the stereotype that Black women are loud and brash:

I make sure I think before I speak at all times. Because I could be pissed off about something and I can’t just go off. I have to think about how am I going to say this? Or what’s a better way to present this? A lot of times I write, I type out what I want to say to someone first and I read it and I may have someone else read it to make sure it doesn’t seem like I’m coming off as the angry Black woman. But I feel like that’s every day, all day, when I’m at work whether it’s here or any other job — that I’m trying to make sure that I don’t give that perception because I don’t want to be that.

Even though all newsroom managers get angry from time to time, anger from African Americans is sometimes less tolerated. Opal said a softer, yet serious approach generally worked better for her:

I said if I’m sitting there and screaming and hollering every day, then it loses its impact. So, if I’m in a meeting and when everybody’s sitting there and applauding our five new promos for the station, and I finally sit there and say, “Hey, did anyone else notice that of those five promos we had no one of color?” And the response from one manager was, “Well, there was that one woman in there. She was just light skinned.” And I said, “You know, that’s not good enough.” And in that exact tone of voice. There was no screaming, hollering, whatever. It just was we have to be better. And was it easy? No. Because there were times when I definitely wanted to go off. But at the same time, I knew that that probably wouldn’t be the best way to do it.

We have already established that a fear of making a mistake or FOMM and a double standard of comportment for these women can lead to extra work in terms of brain energy. In the next chapters, we see how the women disrupt stereotypes in news coverage. Not surprisingly, this too, requires extra work.

Support Journal-isms

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018