Updated Sept. 2.

A trailer for “Behind the Headlines.” The film was shown at the National Association of Black Journalists convention in Cleveland this month and is now on the festival circuit. (Credit: YouTube)

Inaccuracy Erases Others Who Fought

The National Association of Black Journalists, celebrating its 50th anniversary with a film chronicling its progress, is declining to correct a mistake that, aside from its inaccuracy, erases the efforts of those who fought to increase Black representation in newsrooms years before NABJ’s founding.

In the documentary, “Behind the Headlines,” now circulating at film festivals, NABJ co-founder DeWayne Wickham says there was “not a newspaper that had more than three or four” Black journalists when NABJ was founded in 1975.

Journalists who were at the Washington Post, Newsday, the New York Times, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, the Los Angeles Times, the Miami Herald, the Chicago Tribune and the old Washington Star disagree with that assertion, which also does not count those in the Black press.

Alma Robinson, one of those at the Washington Star who responded to an inquiry, messaged, “Since I left in 1972 to go to law school, I can’t contribute to this fact finding effort. But I’m shocked that they were so careless.”

The Washington Post Metro Seven at their March 23, 1972, news conference. From left: Michael B. Hodge, Ivan C. Brandon, Bobbi Bowman, Leon Dash, Penny Mickelbury, Ronald A. Taylor, Richard Prince and attorney Clifford Alexander. (Credit: Ellsworth Davis/Washington Post)

Among those fighting for more Black newsroom representation were the reporters at the Washington Post who became known as the Metro Seven, so named because all were assigned to the Metro desk. The seven, who included this columnist, filed a complaint with the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 1972 charging discrimination in hiring and promotions.

In responding to the Seven then, Executive Editor Benjamin C. Bradlee wrote that the Post had 21 Black editors, reporters and photographers, “more than any newspaper in America.”

Citing their own efforts and those elsewhere, the Seven wrote new NABJ President Errin Haines on Aug. 15, “We wonder whether NABJ’s leadership and co-founder DeWayne Wickham, one of those quoted, would agree to an alteration.”

Haines responded on Aug. 21, “I spoke to Founders Davis and Wickham. Both of them inform me they have no plans to change [the] documentary and asked me to pass their decision along to you.”

The reference was to NABJ co-founder Allison Davis, who spearheaded the film and has said she purposefully did not have a narrator so the story could be told from the memories of those who participated.

Haines added later, “I consider the documentary a good start that is not meant to be a definitive history of NABJ or Black journalism. It is an important part of what I hope will be ongoing storytelling about Black journalists’ contribution to our profession and our democracy.”

One reason cited for the reluctance to correct the mistake has been the cost of altering the film by editing out the quote in question. But others have offered less expensive, creative ways to address the problem. One suggestion has been to append a correction at the end of the film.

Another came from longtime diversity advocate Wanda Lloyd, who in 1973 was among at least eight Black journalists at the Miami Herald. “One solution might be to ask NABJ/Errin to publish a brief release acknowledging the incorrect information in the film, and NABJ suggesting that archival sites archive the release with the film in all places where it might reside, in perpetuity, so the statement follows stories about the film.

“Not perfect solutions, but certainly a rattling of the cages.”

[Others have since replied that with current technology, re-editing is easy and inexpensive. “There are so many editing systems that are used now…..if they don’t know which one to use….they shouldn’t be working on docs,” said Tom Jacobs, veteran of more than four decades in television news and information programming.]

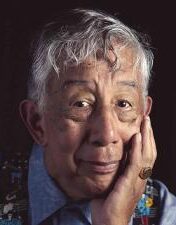

Earl Caldwell recalls early activism by Black journalists in this 2023 interview for the Journal-isms Roundtable. In those earlier years, Caldwell was writing for The New York Times (Credit: YouTube). This “Message to the Black Community” < 226687282_1 > [PDF] is from Black Perspective, a New York-based group of Black journalists, in 1968.

The early 1970s were part of the Nixon years, with the Watergate burglary and Richard Nixon’s 1974 resignation as president among the journalistic and historical highlights.

But they were also years of Black political activism, following the urban uprisings of the 1960s, the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, known as the Kerner Commission, which declared in 1968 that “the journalistic profession has been shockingly backward in seeking out, hiring, training and promoting Negroes.”

In his 2023 book “The Times: How the Newspaper of Record Survived Scandal, Scorn, and the Transformation of Journalism,” Times reporter Adam Nagourney writes that in 1969, a year after the King assassination, Publisher Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger assembled his top editors and managers to say that the low numbers of staffers of color “just isn’t good enough — not good enough for me personally, and not even good enough to meet the legal standards set down by the government.” Two months later, the Times reached out to Paul Delaney of the Washington Star, hiring him as the first African American reporter in the Times’ Washington bureau. He would become an NABJ co-founder.

By 1972, Gary, Ind., hosted the National Black Political Convention. With more than 10,000 attendees, it was the largest independent Black political gathering in U.S. history.

“I remember covering the black conventions with four or more blacks from the Times,” messaged Joel Dreyfuss, another NABJ co-founder. “Tom Johnson. Charlayne [Hunter-Gault], Gerald Fraser and Earl Caldwell. Barbara Campbell was on metro. And don’t forget the critic who was passing: Anatole Broyard.”

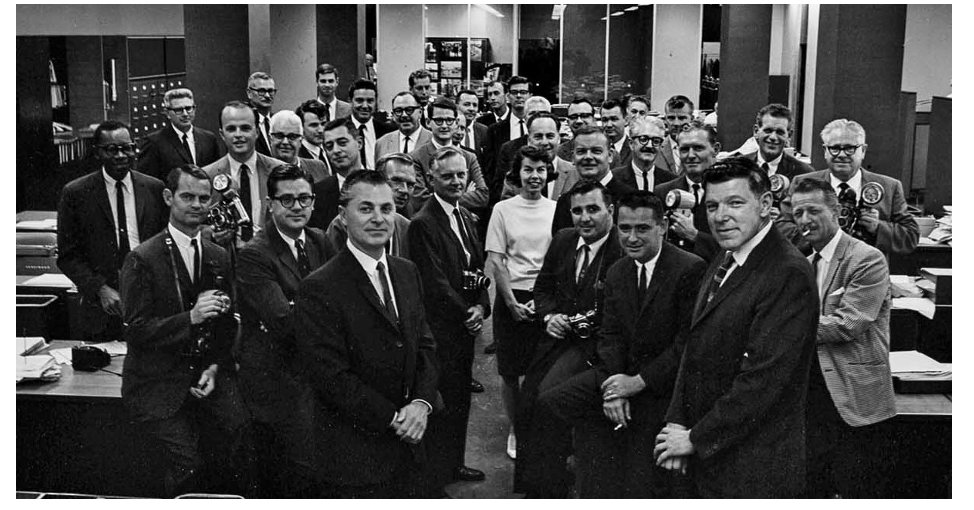

Bill Moyers, in dark suit, with his very white newsroom in his role as publisher. (Credit: Newsday)

Meanwhile, Bill Moyers, longtime aide to President Lyndon Johnson, became publisher at Newsday on Long Island, N.Y., in 1969, and was astonished that there were so few Black journalists on staff. “In 1969, Moyers had made a push to hire six minority reporters outside the normal budget,” including Les Payne, Robert E. Keeler wrote in his 1990 book, “Newsday: A Candid History of the Respectable Tabloid.” The six included Payne, who became one of NABJ’s 44 co-founders and its fourth president.

In 1970, some 50 Black journalists assembled at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Mo. “Nine black reporters and photographers from Newsday became the largest single group at the conference, which played a major role in the development of the National Association of Black Journalists,” Keeler wrote.

Here are other recollections from Black journalists about 1975:

Chicago Tribune

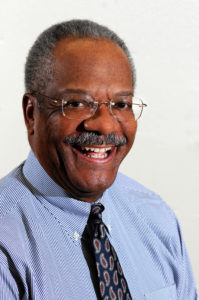

From Clarence Page (pictured)

“As my fuzzy memory recalls offhand, we had my late wife Leanita McClain, Barbara Reynolds . . . and photographers Ernie Cox and Jerry West at that time. Roi Ottley was first and only before Angela Parker and I arrived in 1969.

“I know I am leaving somebody out and I’m sure Barbara remembers better than I do. . . . I do remember that our surge in Black staffers seemed to coincide with the overdue promotions of female staffers in the early 70s after the groundbreaking lawsuit by NYT women.” . . .

“I’ll add that Joe Boyce had been there, but that he had moved on by the mid- 70’s.

“Did I Ieave out Pulitzer-winning photographer Ovie Carter?”

Dallas Morning News

From Norma Adams-Wade (pictured; NABJ co-founder)

The original history of Blacks in the newsroom at The Dallas Morning News.

In 1967, during the “long hot summer” of national racial revolts mentioned in the Kerner Commission Report, The News hired my predecessor, Julia Scott Reed from the Black press. At The News, Reed exclusively covered the Black community in her thrice-weekly column, “The Open Line.” She was very savvy and had mainly educated herself in journalism and photography.

I was hired at The News in 1974 after earning a Journalism degree from the University of Texas at Austin. I was the first African-American at The News to cover news of all ethnic groups citywide.

Therefore, there were two African-Americans on The Dallas Morning News newsroom staff when NABJ was founded in 1975.

I agree with the suggestion that the best – and far-less costly – way to correct the misinformation is to add some kind of note at the beginning or end of the documentary correcting the statement. [Added Sept. 2]

Detroit News and Detroit Free Press

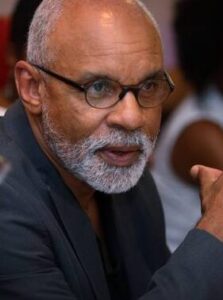

From Vincent McCraw (pictured)

“After checking around, a couple of folks say: Luther Keith, Barbara Young and Henri Wittenberg at the Detroit News. At the Detroit Free Press: Toni Jones, an NABJ co-founder, Susan Watson and Betty DeRamus, as a reporter, Jim Crutchfield and Photographer Hugh Grannum.

“Charlotte Roy, another NABJ co-founder, was also at the Free Press in 1975.”

Kansas City Star

From Gerald B. Jordan (pictured)

I was in the audience for the premier of that documentary and I was jarred by DeWayne’s assertion, but I wrote it off as hyperbole.

The Kansas City Star was an afternoon paper that published a morning edition titled The Kansas City Times, which is where about five reporters and one photographer worked. I worked on Sports, which served morning and afternoon newspapers. The Star staff had three black reporters (that I can recall) and a sister who was religion editor.

Again, this comes from foggy memory, with my sincere apologies for omissions. This memory lane roll call also does not include news interns and Black administrative and professional staff. There were no Black editors who ran a desk or a team of reporters. [Added Sept. 2]

Los Angeles Times

(Courtesy William Drummond)

(Courtesy William Drummond)

From William Drummond (pictured below)

“Brother DeWayne’s information is a bit dated. The [above] photo is the LA Times newsroom in LA around 1967 when I joined. Ray Rogers was the only Black person. If he referenced the late 1960s, he would have been correct. Ray had departed by the early 1970s.

“By 1975 I was in Jerusalem, but a handful of Blacks had joined the paper in LA and in national bureaus. Two Africans were among them, Larry Kaggwa and Tendayi John Kumbula. Stanley O. Williford was on the staff, and there was one Black photographer. Francis Ward was in Chicago. And there was a Brother in the Washington Bureau by then,” since identified as Lee May.

“By 1975 I was in Jerusalem, but a handful of Blacks had joined the paper in LA and in national bureaus. Two Africans were among them, Larry Kaggwa and Tendayi John Kumbula. Stanley O. Williford was on the staff, and there was one Black photographer. Francis Ward was in Chicago. And there was a Brother in the Washington Bureau by then,” since identified as Lee May.

Drummond added:

How could I forget the name of my old friend Mr. Fitz?

New York Times

From Paul Delaney (pictured; NABJ co-founder)

“dewayne is way off re nyt nrs. our newsroom had more than 4/5 blacks. i’ll now name a few — besides me, there were Charlayne [Hunter-Gault], tom johnson, gerald fraser, daryl alexander, tom morgan, barbara campbell, earl caldwell, don hogan charles, ernie holsendolph, fletcher robinson, bill rhoden, reg stuart, roger wilkins, lee daniels, angela dodson, rudy johnson, nancy hicks, mary curtis, howard french, ken noble, al harvin, dwayne draffin, michel marriott, chet higgins, john hicks, diane camper, & a few others i cant recall at the moment. only the post really surpassed us once we started to really recruit [everybody – and i mean everybody – wanted to work for nyt.”]

Delaney acknowledged that those journalists were not all there at the same time.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

From Fred Sweets (pictured)

“I’m testing my memory cells on how many folks were on staff in 1975.

“I’ll call the roll — Fred Sweets, Ellen Sweets, Bob Joiner, Sheila Rule, Gerald Boyd, Linda Lockhart, George Curry, Don Franklin, D.D. Obika, Ted Dargan, Tony Glover and Tommy Robertson. Under Pulitzer we were playing catch-up.”

Washington Star

From Lurma Rackley (pictured)

We definitely had more than three or four. . . .

John White [NABJ co-founder] was there.

Kenny [Walker] was there, for sure.

Adrienne Washington

Mary Ellen Perry (Butler) was there in 1975.

Warren [Howard]

Rudy Pyatt in the business section.

We had two photographers:

Bernie [Boston] and Brig Cabe

From Corrie M. Anders (pictured)

“(I left in the summer of 1975)”

Leon Coates (search link for his name)

Charles Hardy

Kenneth Walker

Jacqueline Trescott

Lurma Rackley

From Jacqueline Trescott (pictured)

Lynn Dunson

“I hope they correct these errors and omissions.”

Bobbi Bowman, veteran journalist, lifetime NABJ member and one of the Metro Seven, said of the need to correct the record, “This is not about us and them. This is about our NABJ’s reputation for accurate reporting.

“I went to two lectures” at this month’s NABJ 50th anniversary convention. “I was so impressed by the young journalists who talked about how they check everything — twice.

“That lesson has been drummed into them, Thank God.”

- Mya Caleb, WVTM, Birmingham, Ala.: History of the National Association of Black Journalists highlighted at Sidewalk Film Festival

Further comments:

Sam Ford, NABJ co-founder, retired reporter at WJLA-TV in Washington, D.C.

Sam Ford, NABJ co-founder, retired reporter at WJLA-TV in Washington, D.C.

Richard, having read your article, I disagree with you and agree with Allison Davis that an inaccurate number by an interviewee in the film is not that significant. It was his recollection of the era, in other words his opinion.

Basically DeWayne Wickham was saying there weren’t a lot of Blacks working in newsrooms at the time. Now had there been a narration of the film, then I would say the number should be exact. That’s supposed to represent facts.

But if there’s an overwhelming insistence that interviewees be accurate to precision in numbers, then I would say make an addition to the credits at the end to say a few newspapers reported more than four Black journalists. And list the numbers as you do in this article, but whether it was four or 21, in the scheme of things the number was relatively small.

Having worked in TV and Radio of that era there were not that many of us. Jet magazine still ran its column to tell its readers where they could see Blacks on TV in a given week because there were so few on TV. [Added Sept. 2]

1 comment

Editor #1 — “Oops! There’s a factual error in the copy.”

Editor #2: “Well, just leave it. It’s too much trouble to be right.”