‘National Hymn,’ but Not a ‘Black National Anthem’

April 7 Is Deadline to Nominate a J-Educator

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible.

‘National Hymn,’ but Not a ‘Black National Anthem’

By Isaiah J. Lewis Poole

Just as conservative culture warriors seem to be moving on from their anger over the Super Bowl performance of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often referred to as “the Black national anthem,” Rep. James Clyburn says he wants Blacks in media to help him relaunch his campaign to make the song “the national hymn of the United States.”

“I would say to all of you good writers: look at this and let’s start the campaign to make ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ our national hymn,” the assistant House Democratic leader told the Feb 19 Journal-isms Roundtable. Since then, his office confirmed that legislation to that effect is to be introduced by Clyburn, D-S.C., in the coming weeks. The bill will be essentially the same as one Clyburn introduced in the 117th Congress when he was Democratic whip, according to a spokesperson.

The song — written by James Weldon Johnson in 1900 and put to music by his brother John Rosamond Johnson — was declared the “Negro national anthem” by the NAACP in 1919, 12 years before President Herbert Hoover signed a bill making “The Star-Spangled Banner” the United States’ official national anthem after a years-long popular campaign.

The decision by the National Football League to present both “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” sung by Sheryl Lee Ralph, and “The Star-Spangled Banner,” performed by Chris Stapleton, at Super Bowl LVII in February drew condemnation from right-wing politicians and commentators. Rep. Lauren Boebert, R-Colo., tweeted, “America only has ONE NATIONAL ANTHEM. Why is the NFL trying to divide us by playing multiple!? Do football, not wokeness.”

This touches on one point on which Clyburn (pictured, by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks) does not disagree. ”One of my pet peeves — and I get in trouble for this as well but I’m gonna say it — is I don’t think we ought to have a Black national anthem,” Clyburn said. “I never liked that. We are one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all, e pluribus unum, [Latin for] out of many one. Let’s be one. Let’s have one national anthem.”

This touches on one point on which Clyburn (pictured, by Sharon Farmer/sfphotoworks) does not disagree. ”One of my pet peeves — and I get in trouble for this as well but I’m gonna say it — is I don’t think we ought to have a Black national anthem,” Clyburn said. “I never liked that. We are one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all, e pluribus unum, [Latin for] out of many one. Let’s be one. Let’s have one national anthem.”

“Lift Every Voice and Sing,” Clyburn said, is “not an anthem, but a hymn” — and he said the Johnson family agrees. (The granddaughter of John Rosamond Johnson, Melanie Edwards, testified in support of the legislation before a House Judiciary subcommittee in February 2022.)

Clyburn continued, “If you read the words, you will find they tell us more about Americans, irrespective of skin color, than anything else.” In an interview with CNN, Clyburn encouraged people to “read the words and think about the experiences that the Irish have had, when they came to this country and what they were running away from. Same thing with Italian Americans. That song can apply to them just as much as it applies to Black Americans.”

Seven years ago, Morgan State University, not far from the birthplace of the “Star Spangled Banner” at Baltimore’s Fort McHenry, produced a documentary on the anthem’s history “and the hidden truths about the third verse of the song” through the guidance of actor, director and producer Tim Reid, and under the direction of DeWayne Wickham, then dean of the School of Global Journalism & Communication.

The Star-Spangled Banner, on the other hand, contains what Clyburn called racist language in its rarely sung third verse, which includes the lines:

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave . . .

Francis Scott Key, author of the song, regarded Black people as “a distinct and inferior race of people, which all experience prove to be the greatest evil that afflicts a community,” wrote Jefferson Morley, author of “Snow-Storm in August: Washington City, Francis Scott Key, and the Forgotten Race Riot of 1835,” in The Washington Post.

The lines in the third verse were intended as a direct rebuke to enslaved Black people who sided with the British because of the promise of emancipation if the British prevailed. Key’s anti-abolitionist, pro-segregation views helped keep the song from winning consensus as the national anthem until a groundswell for the song, coinciding with the entrenchment of segregationist laws and practices throughout the country, finally swept the national anthem bill through Congress.

Morley notes that when the bill passed, its passage was celebrated in Baltimore, the site of the 1812 battle over Fort McHenry, with a parade led by a Confederate flag color guard.

Resistance to the song as national anthem has included a call by the California chapter of the NAACP in 2017 to end that status.

Forty-two people were on the Feb. 19 Zoom call with Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., and Dennis Brownlee, founder of the African American Irish Diaspora Network; 103 had watched on Facebook by March 28 and 130 more on YouTube.

While previous attempts to get other songs designated an official national hymn have floundered, Clyburn said he hopes that for his bill, “good writers like you can get it out of the political arena, where I now have it, and get it passed.”

Forty-two people were on the Feb. 19 Zoom call with Clyburn, D-S.C., and Dennis Brownlee, founder of the African American Irish Diaspora Network; 103 others had watched on Facebook by March 28 and 130 more on YouTube. You may watch the video embedded above or on the YouTube site.

Journal-isms previously reported Clyburn’s comments about former president Jimmy Carter and fellow South Carolinian Nikki Haley, now seeking the Republican presidential nomination.

Clyburn responded to a question about his stance on a federal reparations bill from Trahern Crews,(video), leader of Black Lives Matter Minnesota and member of the city council-created St. Paul Recovery Act Community Reparations Commission. The congressman had a question of his own: “Are you for reparations? Or are you for a soundbite?”

Clyburn said that he succeeded in getting into key portions of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act his “10-20-30” formula, which requires that at least 10 percent of funding in certain government programs be targeted to communities where at least 20 percent of the population has been below the poverty line over the past 30 years. He compared that to H.R. 40, legislation calling for a study and proposal for addressing the historical impact of slavery and systemic racism against Black Americans. For years, it has failed to get traction in Congress.

In late February, Lucy Bustamante of WCAU-TV, the NBC station in Philadelphia, reported on the disparities in benefits for Black and white World War II veterans. Lawrence Brooks, oldest known living U.S. veteran, was receiving $91 a month until his daughter’s intervention resulted in a boost to $2,000 monthly just before Brooks died Jan. 5, 2022, at age 112. (Credit: YouTube)

“Are we going to look at H.R. 40 and say, you got to have the word ‘reparations’? Or when I can do the same, to put 10-20-30, what was I doing? Was that reparations? Someone said to me when I talked about it, ‘So, that sounds like reparations to me.’ I said yeah, that’s what it is.”

The difference, Clyburn went on to say, is that his 10-20-30 plan was able to win some support from Republicans in Congress, but “if I put the word reparations on it, then they aren’t going to touch it.”

Clyburn said that he has reintroduced a bill that would undo the impact of racism in the post-World War II GI Bill, a package of benefits offered to returning soldiers. “Do you realize that [in] the first 3,000 grants [under the GI Bill] only two went to Black people? Not 2 percent. Two.”

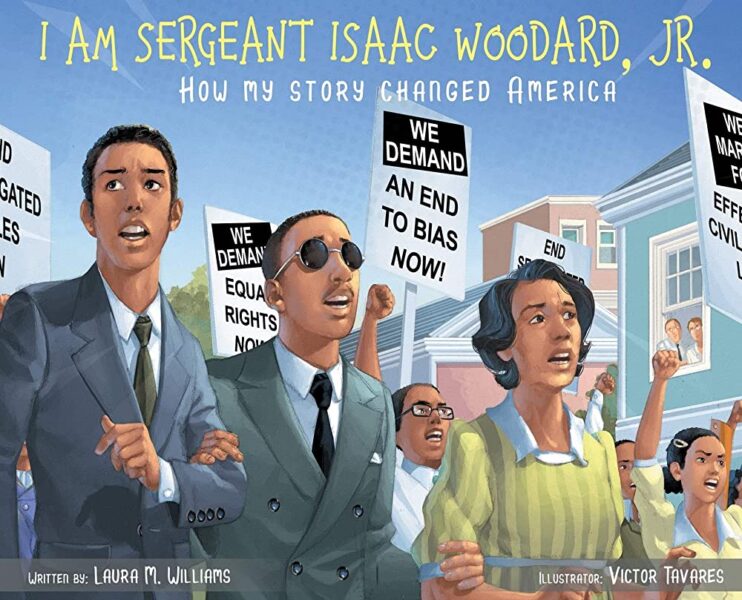

Clyburn’s bill would extend education benefits and loan guarantees to living spouses and direct descendants of Black armed forces personnel who fought in World War II. The legislation is named for Black sergeants Isaac Woodard Jr. and Joseph H. Maddox. In 1946, Woodard was beaten and blinded by a police officer in South Carolina while still in his Army uniform as he was returning home. Maddox was denied benefits to pursue a master’s degree at Harvard by a Veterans Administration official who said at the time he wanted “to avoid setting a precedent.”

“They didn’t get the GI bill, so this will be reparations if we passed a bill,” the congressman said. “But for some strange reason people say, ‘I want the word reparation to be there.’ Well, if you are waiting on that, keep waiting; it ain’t gonna happen. But if you want to get the benefits, let’s come together and put that in the legislation.”

Hazel Trice Edney, editor-in-chief of Trice Edney News Wire, asked Clyburn how he felt about attacks on members of Congress and about his personal safety. Clyburn laid part of the blame on deregulation of broadcast media in the 1980s —- particularly the end of the Federal Communication Commission’s Fairness Doctrine in 1987.

“I think that when we threw out fair comment, when we threw out equal time, when all of that stuff went out the wayside and people felt free under the First Amendment to say anything they want to say, tell any lie they want to tell, say anything about you and you have no recourse — I just think the Fairness Doctrine never should have been gotten rid of.”

The Fairness Doctrine, implemented in 1949, required that TV and radio stations holding FCC-issued broadcast licenses to (a) devote some of their programming to controversial issues of public importance and (b) allow the airing of opposing views on those issues.

Clyburn condemned a “tolerance that people seem to have of certain things that we were intolerable of in years past. We tolerate lying [and] misrepresentation,” specifically citing Rep. George Santos, the New York Republican who admitted to major fabrications in his resumé.

The assistant House Democratic leader also disclosed, in response to a question from author and journalist Barbara Reynolds, that he is working on a book about the first Black members of Congress elected in South Carolina during Reconstruction.

Clyburn said the working title of the book is “Before I was first, there were 8.” He said the title is a reaction to being incorrectly referred to at times as the first Black person to be elected to the House from South Carolina. “That’s not true. I am the ninth black person to represent South Carolina in the United States Congress.”

The first Black person to represent South Carolina in the House — and the first Black person to be elected to Congress from any state — was actually Joseph Rainey, who served from 1870 to 1879. The eighth South Carolinian, George Washington Murray, served two terms, ending in 1897. No other Black person would be elected in a House race in South Carolina until Clyburn in 1993.

- Christina Armeni, The Howard Center For Investigative Journalism, University of Maryland: James Weldon Johnson gave voice to Black people’s dignity and creativity (Jan. 17, 2022)

- Eryn Mathewson and Zoë Saunders, CNN: Why Rep. James Clyburn is pushing to make ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ the US national hymn (Feb. 11, 2021)

- Dominick Mastrangelo, The Hill: CNN’s Don Lemon sings song known as Black national anthem on air ahead of Super Bowl (Feb. 10)

- Holly Honderich and Eloise Alanna, BBC: Why singer Jully Black changed one word in Canada’s national anthem (Feb. 21)

- Cedric Thornton, Black Enterprise: Sheryl Lee Ralph Laughs at Megyn Kelly and Claps Back at Criticism Over Singing Black National Anthem at Super Bowl (March 9)

- Skylar Baker-Jordan, The Independent: Super Bowl 2023: The Conservative outrage over the ‘Black National Anthem’ is predictable and telling (Feb. 14)

- Jeremy Cluff, Arizona Republic: Criticism of Brittney Griner’s national anthem stance renewed after Russia drug sentencing (Aug. 10, 2022)

- Armstrong Williams, The Hill: The NFL’s decision to play ‘Lift Every Voice and Sing’ is a false start (July 30, 2021)

April 7 Is Deadline to Nominate a J-Educator

Beginning in 1990, the Association of Opinion Journalists, now part of the News Leaders Association, annually granted a Barry Bingham Sr. Fellowship — actually an award — “in recognition of an educator’s outstanding efforts to encourage minority students in the field of journalism.”

Since 2000, the recipient has been awarded an honorarium of $1,000 to be used to “further work in progress or begin a new project.”

Past winners include James Hawkins, Florida A&M University (1990); Larry Kaggwa, Howard University (1992); Ben Holman, University of Maryland (1996); Linda Jones, Roosevelt University, Chicago (1998); Ramon Chavez, University of Colorado, Boulder (1999); Erna Smith, San Francisco State (2000); Joseph Selden, Penn State University (2001); Cheryl Smith, Paul Quinn College (2002); Rose Richard, Marquette University (2003).

Also, Leara D. Rhodes, University of Georgia (2004); Denny McAuliffe, University of Montana (2005); Pearl Stewart, Black College Wire (2006); Valerie White, Florida A&M University (2007); Phillip Dixon, Howard University (2008); Bruce DePyssler, North Carolina Central University (2009); Sree Sreenivasan, Columbia University (2010); Yvonne Latty, New York University (2011); Michelle Johnson, Boston University (2012); Vanessa Shelton, University of Iowa (2013); William Drummond, University of California at Berkeley (2014); Julian Rodriguez of the University of Texas at Arlington (2015); David G. Armstrong, Georgia State University (2016); Gerald Jordan, University of Arkansas (2017), Bill Celis, University of Southern California (2018); Laura Castañeda, University of Southern California (2019); Mei-Ling Hopgood, Northwestern University (2020); Wayne Dawkins, Morgan State University (2021); and Marquita Smith of the University of Mississippi (2022).

Nominations may be emailed to Richard Prince, Opinion Journalism Committee, richardprince (at) hotmail.com. The deadline is April 7. Please use that address only for NLA matters.

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)