For Journalists, Researching Family History Can Be Life-Changing

Homepage photo: Children of Lee Hawkins’ great-great grandfather, Private Isaac Blakey, on their family farm in Missouri, which the family purchased shortly after enslaved people were emancipated in the U.S. Blakey himself endured slavery for 16 years before joining to fight for the Union in the Civil War. (Photos courtesy Lee Hawkins)

Journal-isms Roundtable photos by Jeanine L. Cummins

[btnsx id=”5768″]

Novelist Amy Tan on set with “Finding Your Roots” host Henry Louis Gates Jr. Such television shows have normalized genealogy research. (Credit: PBS)

Researching Family History Can Be Life-Changing

By Tolu Olasoji

Want to boost your confidence, pride and sense of identity? Try digging into your family history, even if you’re African American and the trail leads back to slavery.

That’s the powerful message from four veteran Black journalists who discovered that researching their enslaved ancestors didn’t just fill gaps in family knowledge. It transformed how they see themselves, their work and how far they go back in America.

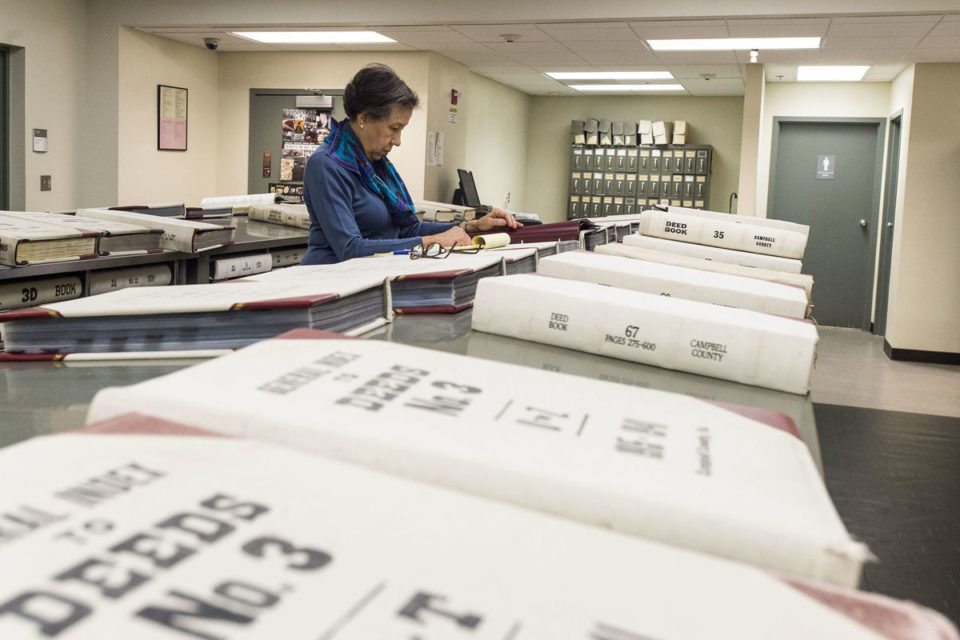

The moment still gives Bobbi Bowman chills. Standing in a Virginia courthouse in 2010, hunting for property deeds, the former Washington Post reporter stumbled across something impossible: her great-great-grandfather’s name in an 1871 land record. But William Williamson wasn’t supposed to own property. Her family stories said their ancestors “walked out of slavery with nothing but the clothes on their backs.”

“Why is Grandma Mariah’s name in a deed book?” Bowman said out loud in the empty document room of the Campbell County Courthouse. “Our family has never owned any land.”

What she discovered next defied everything she thought she knew about survival, choice and love under slavery. (Photo: Bowman searches through records at the Campbell County, Va., Courthouse in Rustburg on Feb. 7, 2018. [Credit: Jay Westcott/News & Advance] )

What she discovered next defied everything she thought she knew about survival, choice and love under slavery. (Photo: Bowman searches through records at the Campbell County, Va., Courthouse in Rustburg on Feb. 7, 2018. [Credit: Jay Westcott/News & Advance] )

In 1842, Williamson had bought his freedom. Then he voluntarily returned to slavery to stay near his wife and children. Virginia law gave freed Black people one year to leave the state or face re-enslavement. He chose love over liberty and 100 acres of land that would later return to his family after the Civil War.

“I had never heard a story like this, much less in my own family,” Bowman reflected during June’s Journal-isms Roundtable, “Journalists Confronting Family Histories That Include Slavery.” “That’s when I knew the ancestors had finally come for me.”

Despite persistent myths about the impossibility of tracing African American ancestry, these journalists prove that such genealogical research is possible and transformative.

The barriers, they found, are real and systemic: Enslaved people were often recorded only by first names in estate inventories; census records before 1870 didn’t name them at all; families were deliberately separated and literacy was prohibited. This created what genealogists call the “1870 Wall,” a reference to the first census to name formerly enslaved individuals. It left researchers with little documentation to trace families further back.

However, creative research methods, oral histories and previously overlooked records can crack open even the most challenging ancestry puzzles.

Bowman joined Charles Fancher, former Philadelphia Inquirer and Detroit Free Press editor; Lee Hawkins, 2022 Pulitzer Prize finalist and former Wall Street Journal reporter; and Lonnae O’Neal, former Washington Post journalist and senior writer at Andscape. They spoke, along with other journalists and aspiring authors, at a Journal-isms Roundtable that left viewers utterly engaged.

Forty-seven people were on the call, and as of June 20, another 66 had taken it in on YouTube. Click to view.

The Roundtable also featured an update on the Fallen Journalists Memorial, planned for Washington, D.C., inspired by the 2018 shooting at the Capital Gazette office in Annapolis, Md., in which five staffers were killed. It was the largest shooting of journalists in the nation’s history. Plans are for an opening in June 2028, on the 10th anniversary of the shooting.

Weeknight anchor Lorenzo Hall of WUSA-TV in Washington shows the first images released of the proposed memorial, due to open (Credit: YouTube)

“The memorial design engages with themes of transparency and light,” said Barbara Cochran, president of the Fallen Journalists Memorial Foundation. “Issues important to the work of journalists and photojournalists. Solid glass elements are stacked horizontally to represent the fallen.” She was accompanied by John Yearwood , editorial director, diversity and culture at Politico and a supporter of the memorial.

The family discoveries by the author-journalists take on new urgency at a charged moment. The Trump administration’s April deadline for removing “radical indoctrination” from K-12 schools threatens federal funding for teaching systemic racism. The years-long family research of the panelists proves the very historical patterns lawmakers want erased and reveals the complex strategies their ancestors used to survive America’s original sin.

Fancher’s (pictured) revelation came when his 90-something mother, Evelyn P. Fancher, PhD., a retired chief librarian at Tennessee State University in Nashville, suddenly opened floodgates of family memory.

Fancher’s (pictured) revelation came when his 90-something mother, Evelyn P. Fancher, PhD., a retired chief librarian at Tennessee State University in Nashville, suddenly opened floodgates of family memory.

For decades, she’d been notoriously private. Then one day, “maybe the stars were aligned in some special fashion, she just started talking,” he said.

Out poured discrete memories about her grandfather that didn’t form complete history but “provided a thread I could pull to bring it all together.” His mother followed up with “page after page of handwritten anecdotes” that became the foundation for his novel, “Red Clay.”

The research revealed how “Black people have always found a way to survive and even thrive in adversity.” His great-great grandfather, Plessant, “survived by taking every advantage that he could from what he found in the condition that he was in, enslaved on a southern Alabama plantation.” His great-grandfather. Felix, “survived and prospered through Reconstruction and Jim Crow.”

This theme of inherited resilience inspired Hawkins’ research for “I Am Nobody’s Slave.” His memoir explores how his family navigated systemic racism across generations, tracing the ways trauma from slavery and segregation influenced their pursuit of success.

O’Neal (pictured) went beyond documentation to reclamation. Researching “Bibb Country,” she discovered her fourth great-grandmother, Keziah, was enslaved by Kentucky’s Bibb family, whose patriarch developed the lettuce strain still sold in grocery stores. But she rejected the dehumanizing “naming convention” used by “traffickers” who called her ancestor “Old Keziah.”

O’Neal (pictured) went beyond documentation to reclamation. Researching “Bibb Country,” she discovered her fourth great-grandmother, Keziah, was enslaved by Kentucky’s Bibb family, whose patriarch developed the lettuce strain still sold in grocery stores. But she rejected the dehumanizing “naming convention” used by “traffickers” who called her ancestor “Old Keziah.”

Instead, she honored her as “Mama Kaziah.”

“Once you can name something, you can tell it what to do,” O’Neal declared, explaining how this shift in perspective “opened up the story for me, because it changed my position in the story.”

Technology has transformed genealogical research, making it far more accessible than previous generations could imagine. Platforms such as FamilySearch.org and ancestry.com help researchers overcome brick walls that once seemed insurmountable for Black families.

Television shows like “Finding Your Roots,” with Henry Louis Gates Jr., have normalized genealogy research, while such celebrities as Issa Rae, Jordan Peele and Regina King publicly document their ancestral journeys. Recently, on a YouTube lifestyle show, Tina Knowles, matriarch of Beyoncé’s family, revealed how she traced her ancestors through a manifest on a ship sailing to Louisiana.

These high-profile discoveries are normalizing conversations about family history. When white smoke announced Pope Leo XIV’s election at the Vatican, social media exploded with ancestry speculation in the United States, about potential Louisiana family connections, sending curious netizens racing to genealogy databases to trace possible bloodlines to the new pontiff.

“I loved that somebody went to ancestry.com after hearing his last name and being from the South,” Bowman said, laughing, “and was like, ‘Yeah, that could be my uncle.’ “

A Room Full of Breakthroughs

The conversation expanded as other attendees and researchers told of their stunning family revelations.

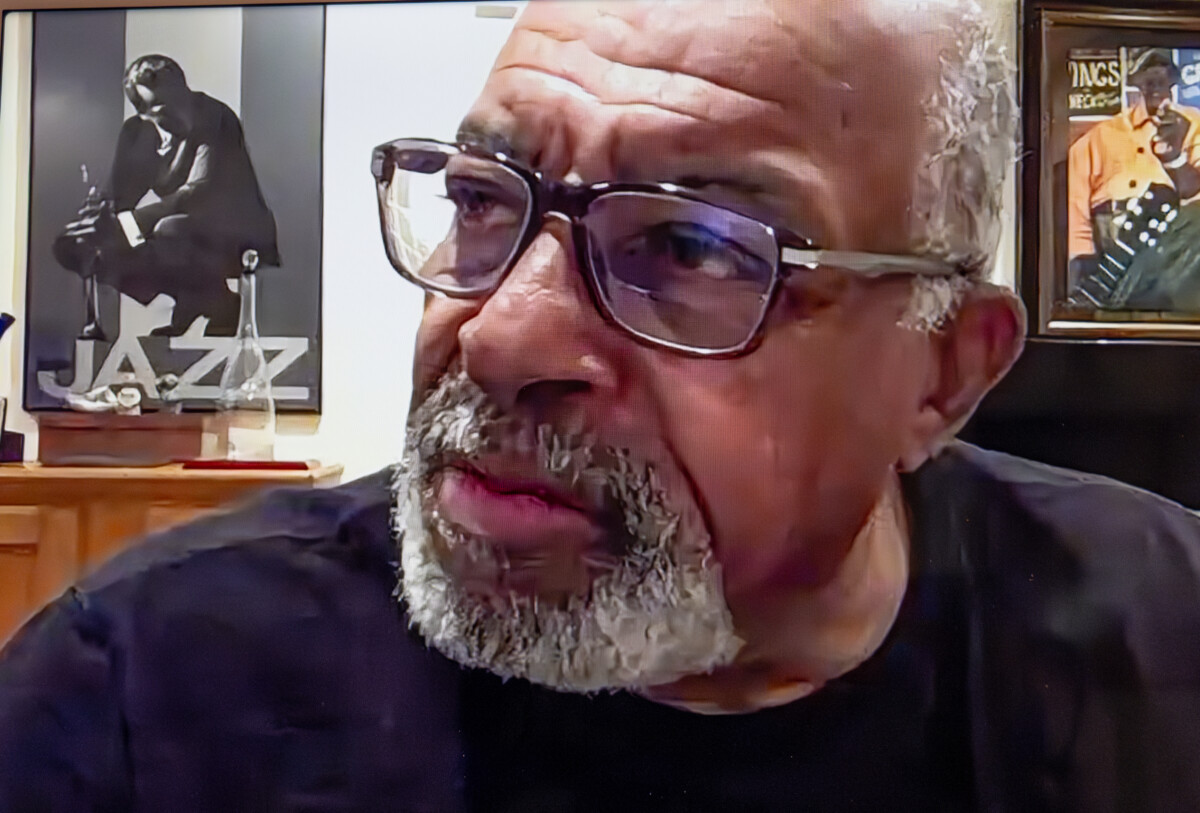

Rodney Brooks (pictured), veteran business journalist and author on Black financial topics, traced his ancestry to John Butler, born in Nigeria in 1650 [PDF] and enslaved in Maryland just an hour from where Brooks lives today. Walking the cemetery where his great-great-grandfather David was buried, even without finding the gravestone, gave him “this great feeling to know that my ancestors were there,” he told the group.

Rodney Brooks (pictured), veteran business journalist and author on Black financial topics, traced his ancestry to John Butler, born in Nigeria in 1650 [PDF] and enslaved in Maryland just an hour from where Brooks lives today. Walking the cemetery where his great-great-grandfather David was buried, even without finding the gravestone, gave him “this great feeling to know that my ancestors were there,” he told the group.

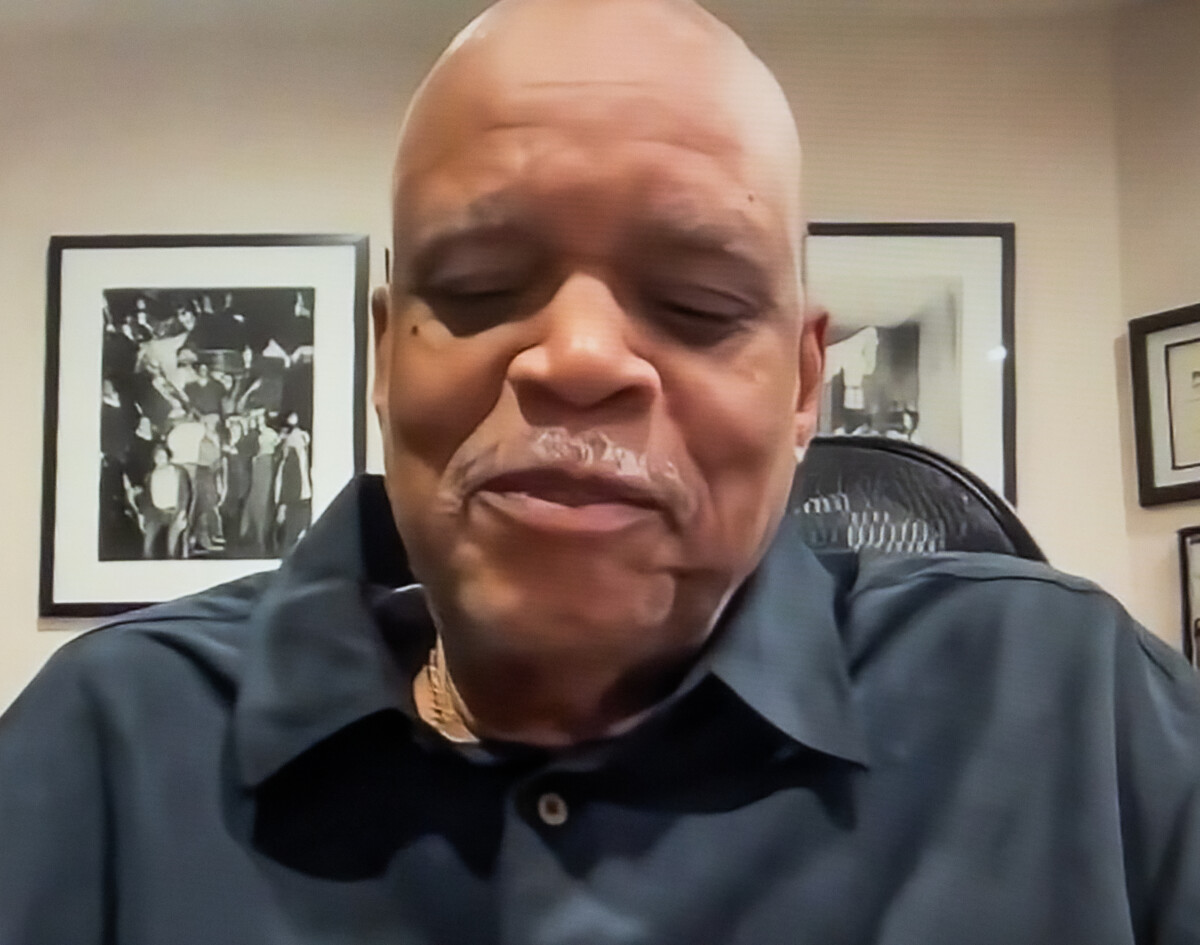

Pulitzer Prize winner Kenneth J. Cooper (pictured) discovered his maternal ancestors were enslaved by Cherokee Indians in Georgia and later Oklahoma. His book, “On Lightning: A Rainbow Family in the Cherokee Nation,” is due in September. It documents how Black men in his family adopted survival strategies during slavery and Jim Crow, including relatives who passed for white during World War I to fight as soldiers rather than laborers.

Pulitzer Prize winner Kenneth J. Cooper (pictured) discovered his maternal ancestors were enslaved by Cherokee Indians in Georgia and later Oklahoma. His book, “On Lightning: A Rainbow Family in the Cherokee Nation,” is due in September. It documents how Black men in his family adopted survival strategies during slavery and Jim Crow, including relatives who passed for white during World War I to fight as soldiers rather than laborers.

Author and journalist Angela Dodson befriended a white descendant of the Hairston family, possibly “the largest slave holding family in America,” and they are collaborating on a book about their shared but vastly different inheritance.

In his newly published “Descended,” Keith Rushing (pictured) documented his Gullah heritage on Hilton Head, S.C., celebrating ancestors who “chose to live separately” after emancipation, building self-sufficient communities where “they fished, farmed, built their homes, raised their children and churches.”

In his newly published “Descended,” Keith Rushing (pictured) documented his Gullah heritage on Hilton Head, S.C., celebrating ancestors who “chose to live separately” after emancipation, building self-sufficient communities where “they fished, farmed, built their homes, raised their children and churches.”

The research fuels action. Roger Witherspoon came of age in the 1960s and spent nine years on the board of the Society of Environmental Journalists. He grew up hearing his grandfather’s stories about ancestors fighting the Ku Klux Klan and used those lessons when facing neo-Nazis at the University of Michigan. “It was so personally invigorating,” he reflected after the Roundtable, crediting family stories with “putting the lie to the white myth of docile Negroes.”

The panelists stressed fierce urgency about collecting stories. O’Neal lost four relatives during her book research; one died a month before she could interview her. “You have to talk to the oldest people in your family first,” she advised. “The documents will be there.”

“You have to get it while you can, because those people aren’t going to be on the scene forever,” Fancher added.

The mother of Hazel Edney (pictured), founder of the Trice Edney Wire, a news service for the Black press, has Alzheimer’s dementia. Edney expressed a personal note of regret: “There’s so much that I wish I had asked her. And so if you’re going to talk to them, if you’re going to do it, do it now before anything like that kicks in.”

The mother of Hazel Edney (pictured), founder of the Trice Edney Wire, a news service for the Black press, has Alzheimer’s dementia. Edney expressed a personal note of regret: “There’s so much that I wish I had asked her. And so if you’re going to talk to them, if you’re going to do it, do it now before anything like that kicks in.”

Confronting Uncomfortable Truths

Not all discoveries bring comfort. Haitian-American journalist Joel Dreyfuss (pictured) found Black ancestors who owned slaves, a reality that shatters simple narratives about oppression and resistance. “In Haiti, one-third of all the slaves were owned by free people of color,” Dreyfuss explained, referring to the complex colonial system in Saint-Domingue where mixed-race free people accumulated significant plantation wealth.

Not all discoveries bring comfort. Haitian-American journalist Joel Dreyfuss (pictured) found Black ancestors who owned slaves, a reality that shatters simple narratives about oppression and resistance. “In Haiti, one-third of all the slaves were owned by free people of color,” Dreyfuss explained, referring to the complex colonial system in Saint-Domingue where mixed-race free people accumulated significant plantation wealth.

The pattern emerged in American South. In Louisiana, 40 percent of free Black families owned slaves. In South Carolina, the figure hit 43 percent. These statistics reveal the brutal economic pressures that led some formerly enslaved people to participate in the system that had brutalized them.

“I’m less judgmental about people who were slave owners,” Dreyfuss reflected, “because it was a prevailing economic system, and even free Black people wanted to build wealth.” His research also revealed that French colonial record-keeping gives researchers advantages that American genealogists often lack. In “some countries, the documentation is better. The French kept very good records,” Dreyfuss explained, noting that Haiti’s colonial records were preserved in Europe while American documents were frequently lost.

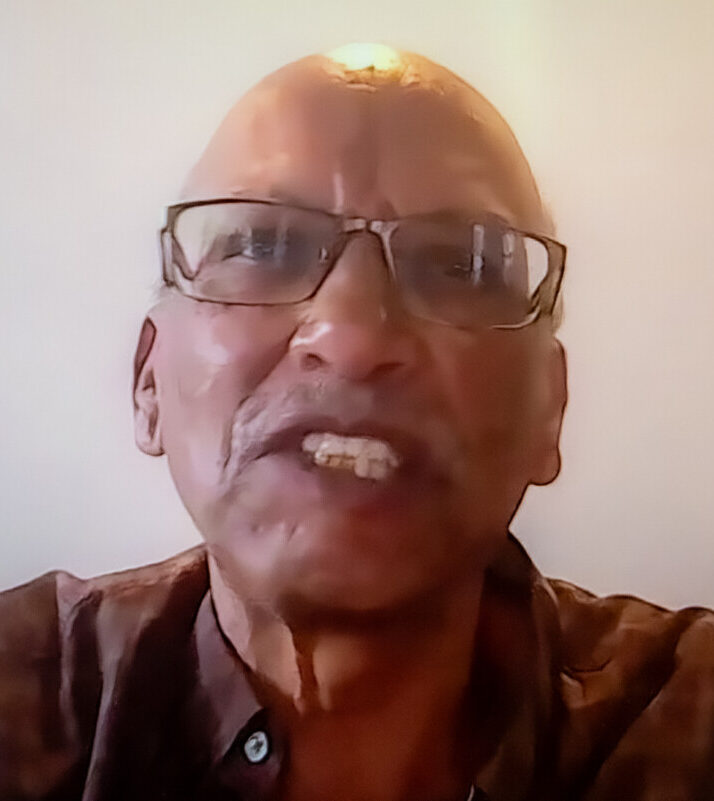

Leon Dash’s (pictured) experience shows how families themselves sometimes participate in historical erasure. The retiring University of Illinois journalism professor, who researched his family from 1994 to 1998, discovered that much of what he’d been told was false. His investigation revealed that two great-great-grandfathers born in slavery were full brothers whose children married each other, first cousins whose union his family had tried to cover up for generations.

Leon Dash’s (pictured) experience shows how families themselves sometimes participate in historical erasure. The retiring University of Illinois journalism professor, who researched his family from 1994 to 1998, discovered that much of what he’d been told was false. His investigation revealed that two great-great-grandfathers born in slavery were full brothers whose children married each other, first cousins whose union his family had tried to cover up for generations.

“I’ve been given a lot of misinformation,” Dash said, noting how the research made him “very introspective” despite his family’s disapproval of his discoveries”

How Genealogical Discoveries Shape Their Journalism

For these journalists, the genealogical research doubles as professional resistance. As Hawkins (pictured) warned, mainstream outlets showed less commitment to racial justice stories after the 2020 police murder of George Floyd sparked temporary interest. “I now realize it was a trendy time,” Hawkins said, noting that “people who describe themselves as allies have thrown in the towel very quickly” after President Trump’s sweeping directives.

For these journalists, the genealogical research doubles as professional resistance. As Hawkins (pictured) warned, mainstream outlets showed less commitment to racial justice stories after the 2020 police murder of George Floyd sparked temporary interest. “I now realize it was a trendy time,” Hawkins said, noting that “people who describe themselves as allies have thrown in the towel very quickly” after President Trump’s sweeping directives.

Hawkins explained how this affects working journalists: “I’ve even had one company ask if they could see my speech before I spoke.” He urged Black journalists to take control of their narratives, emphasizing the need for long-form storytelling that captures the full depth and complexity often missing from mainstream coverage.

According to Bowman, reporters need to “be more like historians.” She regretted that she once treated each story as isolated. “Everything has a history. Every issue that we cover, every person that we look at has a history.”

A’Lelia Bundles (pictured) is author of the just-published “Joy Goddess: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.” Her 2001 biography of her entrepreneur great-great-grandmother, Madam C.J. Walker, was adapted into the 2020 Netflix series “Self Made” starring Octavia Spencer. Bundles noted that increased historical knowledge is creating irreversible change. The current backlash to expanded scholarship in the last five decades “is what we’re seeing now,” she said, “but you cannot put that back in the bottle.”

A’Lelia Bundles (pictured) is author of the just-published “Joy Goddess: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance.” Her 2001 biography of her entrepreneur great-great-grandmother, Madam C.J. Walker, was adapted into the 2020 Netflix series “Self Made” starring Octavia Spencer. Bundles noted that increased historical knowledge is creating irreversible change. The current backlash to expanded scholarship in the last five decades “is what we’re seeing now,” she said, “but you cannot put that back in the bottle.”

Bundles said she understands how history is deliberately distorted. “When I was in high school in the late ’60s, my high school history textbook said that slaves were contented and better and freer people because they were clothed and fed,” she recalled. That false narrative came from the Dunning School, “a racist line of thought, “and the United Daughters of the Confederacy, who were infusing themselves into the curriculum.

“That’s the same mindset that we are confronting right now,” Bundles said, explaining why ancestral research has become urgent resistance work. “It’s a really wonderful journey when the ancestors talk to you and insist that you pay attention to them. And we obviously have these great stories that need to be told, especially in this moment when our history is being erased.”

How to Research Your Family History

Want to know how far back your family history goes, but don’t know where to start? The panelists offered tested and trusted advice:

- Talk to family first: Record conversations at reunions. Interview elderly relatives on Zoom. Create oral histories even without an immediate purpose.

- Visit courthouses: As Bowman learned, “Courthouses are secret keepers.” Property deeds, marriage records and court proceedings often contain surprises.

- Combine digital with traditional methods: Use ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org, but cross-reference with DNA testing, historical records and family stories.

- Think like a historian, and use journalistic skills: Cross-reference sources. Look for patterns. Question official narratives. Connect personal stories to larger historical movements and events. The panelists’ successes came from combining a historical perspective with journalistic rigor.

- Start now: Don’t wait for perfect conditions or complete information.

Their message resonates beyond newsrooms, especially in an era when lawmakers want to sanitize America’s original sin. But journalists are proving that the past remains present. Don’t wait for textbooks to tell these stories. Every family story uncovered, every courthouse document found, and every elderly relative interviewed becomes an act of historical preservation. The most powerful story you might ever tell is waiting in your bloodline.

Tolu Olasoji is a New York-based producer/journalist and member of the New York Association of Black Journalists.

- Susan Benkelman, American Press Institute: The power of intergenerational storytelling to solidify community and effect change (June 4)

- Tommy Christopher, Mediaite: CNN Anchor [Abby Phillip] Torches Trump For Erasing Black Icons and Exalting ‘Confederate Traitors’: ‘What Are We Doing Here?’ (June 4)

- Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Philadelphia Inquirer: Universities holding African American artifacts must shift from a focus on property to one of repair (June 11)

- Henry Louis Gates Jr., New York Times Magazine: Finding the Pope’s Roots

- Erica L. Green, New York Times: How Trump Treats Black History Differently Than Other Parts of America’s Past

- Jaylen Green, Associated Press: The home of one of the largest catalogs of Black history turns 100 in New York (June 14)

- Beatrice Lawrence, Wisconsin Public Radio: Author examines history of violence toward Black people by ‘uncovering’ his family history (Feb. 3)

- Alex Presha, ABC News: 10 Million Names’ and ABC News explore recordings of formerly enslaved individuals (March 1, 2024)

[btnsx id=”5768″]

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- “Black Journalists Will Figure in Jimmy Carter’s Legacy” on Sirius XM’s “Urban View Mornings.” (video) (Jan. 3, 2025)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World