Excerpt: Microaggressions, Even If You’re the Boss

Support Journal-isms

Excerpt: Microaggressions, Even If You’re the Boss

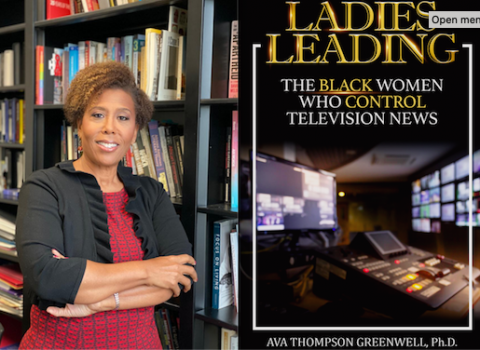

With the recent ascensions of Black women to top management roles in broadcast and print journalism, a new book by Ava Thompson Greenwell, Ph.D, “Ladies Leading: The Black Women Who Control Television News“ (Royston Publishing) assumes fresh relevance.

Greenwell teaches reporting classes at the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications at Northwestern University. “This book brings Black women television news managers out of the shadows and accounts for both their race and gender, building a primary archive of interviews with 40 news leaders,” she writes in her introduction.

“Their stories document continued workplace bias and demonstrate the harmful inequities that exist, even when you’re the boss.”

In this excerpt from the book, as well as in the complete work, names of individuals, places and stations have been substituted with pseudonyms or generic identifiers. “I replaced most of the women’s names with flowers or gemstones. Flowers symbolized their ability to grow and bloom, despite sometimes poor nurturing conditions. Gemstones symbolized their strength and endurance to weather the storms of news,” Greenwell tells us.

This is the first of two parts of her chapter, “Suppressing Self: Hair, Body Parts and Tongue.”

By Ava Thompson Greenwell, Ph.D.

“I might be shaking my shoulders … to my music, but I’m aware when I’m getting into the city — even as big as the city is, you want to tone that down a little bit.”

— Lavender, television news manager

The weight of the various microaggressions women like Lavender experienced was heavy. One way some chose to alleviate the pressure was to conform to newsroom norms of dress and conversation. Although most people are expected to dress and speak appropriately in a professional work environment, for Black women, “acting” professional takes on a more urgent meaning, given the history of Black women’s access to professional settings.

Since Black women, in particular, have not been at the table of board room meetings, their presence as leaders in editorial meetings was, and still is, rare.

To understand the pressure Black women sometimes face to look and sound the part of a newsroom executive, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham’s “politics of respectability” is helpful in understanding the unstated, often self-imposed, ways the women proved they belonged. In other words, the women chose to wear their hair, dress and speak in respectable ways, to be seen as more acceptable to their white subordinates, colleagues and supervisors.

In a 2002 survey of news managers of color, a majority answered “yes” when asked whether they changed their dress, hair and/or behavior when they arrived at work.

The reason – to better fit in and make their white colleagues and supervisees feel more comfortable. Because the women described in this book were supervisors with the authority that came with the title, they were not overly concerned about subordinates’ comfort level with them. However, anxiety surfaced when the women spoke about their interactions with peer managers and higher-level supervisors. For example, the topic of “hair” came up numerous times when the women were asked whether they changed their physical appearance while at work.

History of Black Women’s Hair

Black women’s hair has had a tortured history in the United States. Madam C. J. Walker has been popularized on film as one of the first self-made, female millionaires because of her Black hair care empire, developed in the late 1800s to straighten tightly coiled hair.

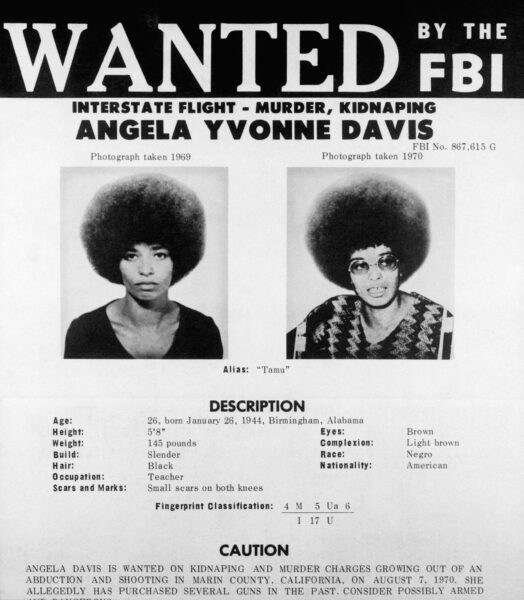

Furthermore, the idea of Black beauty and hair has long been associated with a Black politics of resistance. By the 1960s Black Power Movement, some Black women and men resisted straightening their hair as a way to reject European beauty standards. Instead, they showed off their naturally textured hair, embracing a “Black is beautiful” mantra. Political activist and scholar Angela Davis’ iconic Afro became a symbol of resisting white oppression. By the 1970s, advertisements targeted at straightening Black hair expanded to include ads for products to create the perfect Afro.

The style of Black hair that is deemed appropriate in corporate work environments has been the subject of numerous newspaper articles, scholarly and popular books, magazines and even lawsuits.

In 2019, Black women television journalists who wore natural hair styles on camera posed for a historic picture at the National Association of Black Journalists convention to show how times had changed. Although television newsroom culture has become more accepting of natural hairstyles, the industry has a history of rejecting Black women’s unaltered hair.

When Melba Tolliver refused to straighten her hair in 1971, she made a bold statement. She was the first Black woman to appear on camera on a national news broadcast with her hair in a natural style. She had already appeared wearing an Afro on the local New York station and reportedly had been told by her news director, “I hate your hair. You’ve got to change it. And you know what, you no longer look feminine.” Just before she was videotaped wearing her Afro for a segment covering the wedding of President Richard Nixon’s daughter, network executives asked her to put on a wig or scarf. She refused and editors deleted the segment of her appearing on camera with her Afro.

In the 1970s, on-air reporter Renee Ferguson’s television news bosses told her to change her hair when she appeared on camera wearing an Afro, asserting she looked too militant. Not much had changed by 2007 when Ferguson again tried to wear a short Afro style on-air. This time it was not a white male, but her African American female news director who ordered her to return to her straightened style.

The fact that it was a Black woman news director who refused to allow her to wear her hair natural on camera speaks to the strength of straight-hair preference. Both her bosses were convinced straight hair was the only acceptable style for television audiences.

Since the women featured in this book generally do not appear on camera, natural hairstyles were more acceptable. Yet some of those integrating newsroom management ranks for the first time chose assimilationist styles as a mechanism of self-preservation and ease of maintenance. They perceived that if the institution did not like their natural hair, it would not like them either. Those who wore natural styles, such as Afros, braids or dreadlocks, sometimes received subtle cues about the way to wear their natural hair.

For example, Cassia, an executive producer and assistant news director in one of the most populous news markets with a Black population over 30 percent, said the more she suppressed or corralled her natural hair, the more positive attention she received:

With my dreads pulled back in a bun; it was a little bit more conservative. And the response was, I appeared friendlier, I guess. My hair wasn’t in my face. It wasn’t down or whatever. And then people in the hall would say, “Oh, you look so nice today” because it’s pulled back in a ponytail.

With her hair styled down and out, it meant she was less friendly, less conservative — even angry. Yet, according to Cassia, there were times when her bosses did not want “friendly and conservative,” especially when she attended a corporate party with mostly white men:

It was a dinner, a gala. When I got there the GM (general manager) said, ‘”What? Why did you put your hair up?” I was too conservative for him. He wanted me to walk in like this exotic wild animal. You know I pulled up and he said . . . You have it pulled back. I wanted it out.”

The fact that her manager said, “I wanted it out,” indicated he thought he had some ownership or agency over how she wore her hair. The idea of being able to control the hairstyle of one of your employees seems out of sync with most 21st century workplace norms.

Controlling Black women’s every move has a long history in the U.S., some of which involved more serious repercussions, such as the sexual violation of Black female bodies. Autobiographies, such as Harriet Jacobs’ “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” underscore how Black women rarely had full control of anything, especially their own bodies. They could not refuse a white man’s sexual advances or violations. Nor could they decide where they worked, when they wanted to work or how they worked.

Perhaps Cassia’s boss thought wearing her hair the way he wanted was part of the job description. Because he was her “overseer,” he thought he could control her look outside of the workplace to his liking and desire. Clearly, she disagreed and, through her own agency, decided for herself how she wanted to wear her hair.

In other cases, newsroom conversations about hair provoked anxiety among the women. Blossom said talk about natural hairstyles often fostered unnatural responses: “I mean they [her newsroom colleagues] would say stuff when I had braids. And I only did that one time and they said, ‘Oh, aren’t those cute’ and all the stupid questions. But I didn’t feel like they wanted me to take them out because I wasn’t [going to remove them].” The tone in which the so-called compliment was delivered did not sit well with Blossom. To her, she had just experienced a microaggression.

Topaz said she also preferred to avoid hair questions, “My hair, I am natural. So, on the weekends I’ll wear it natural, but I won’t wear it natural [without some straightening technique] to work because I don’t want questions such as, ‘How did you do that? Did you cut your hair? What is this?” Despite being a manager, she chose to straighten her natural hair five days a week to better fit in, instead of drawing attention to the fact that Black women’s hair comes in a variety of textures and styles. Both Cassia and Topaz referred to the questioning as more than just annoying, but as a sign of ignorance about the history and culture of Black women’s hair.

Go Along to Get Along

Generally, the women explained that early on in their careers, their main coping technique involved doing what it took to be treated with the type of respect a manager deserved. Sometimes that meant trying to distinguish herself by not standing out as different. Their strategy was to get in, fit in, show competence and make changes once inside. They did not want to be questioned ad nauseam about the details of their hair so they avoided those conversations.

Different points of view about the subject of “natural” versus “relaxed” hairstyles emerged among the Black women television news managers I interviewed. Turquoise said newsroom aversion to natural hairstyles such as Afros and braids was more perception than reality and was another burden women of African descent sometimes imposed upon themselves:

“I remember when I first got the braids, a Black friend, not a co-worker, said, ‘You know, I don’t think you should do that. You know, you work here.’ And of course, they (her co-workers) loved it. I mean white people really don’t care about our hair.” Turquoise concluded that African American women who work behind the camera and who worry about whether wearing a natural hairstyle will stifle their careers are grappling with their own negative thoughts about their hair. That is, they are choosing to wear only straight hairstyles because that is what they think their bosses want.

Although Melba Tolliver and Renee Ferguson were told explicitly not to wear natural hairstyles, none of the off-camera women in this book received such a directive. Instead, some responded to their implicit understanding from history, previous encounters in professional work environments and messages passed down from previous generations. As part of their daily preparations for work they had to consider more than a century of the devaluing of textured, kinky, tightly coiled hair and its subjugation to various states of heat and chemical alteration.

Opal agreed that resistance to natural hair did not always come from white people in the newsroom: “I remember looking in the mirror and going ‘I can get an extra half hour out of my day … if I cut my hair off and go natural. And I did. And I’ll tell you what, I got more questions at the beauty shop than anywhere else, where the woman [Black stylist] asked: ‘Are you sure you want to do that? Are you sure?’”

Emerald acknowledged “the hair” issue was her issue: “I can’t get past that mentally. Because if you see me at home on a weekend … my hair … I wash it and I’m wearing natural hair. You know, and I’ll say to my husband, ‘Oh, I wish I could go in to work like this.’ And he’s like, ‘Well, you can.’ And I’m like, ‘but I can’t.’ ” Emerald’s own thinking stopped her from being her true self.

In one instance, a natural hairstyle seemed to inhibit a participant’s upward mobility. A mentee of Venus said the station’s white male news director treated Venus more poorly once she began wearing her hair in a natural style:

“The straw was when she cut her hair and she was growing out a [chemical] relaxer which we have all dealt with and so it was in that awkward state. It was like you could just see his disdain. She did not fit with anybody and he (the news director) was not going to confide in her and everybody knew it.” While this type of reaction was extreme, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, employment discrimination based on hair texture still occurred but was hard to prove. Therefore, some participants said they wore braids or other non-straight styles only after they had established their stature and longevity as managers.”

Next: Part Two — Not wanting to appear the “Angry Black Woman.”

- Patrice Peck, New York Times: Hiring, Firing, Setting the Culture: Black Women at the Top of TV News (July 10)

- Journal-isms: ‘Good Hair’ on the TV Set (Oct. 8, 2009)

- David Person with Melba Tolliver: The Afro: Personal Reflections (Jan. 1, 2005) (audio)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)

When you shop @AmazonSmile, Amazon will make a donation to Journal-Isms Inc. https://t.co/OFkE3Gu0eK

— Richard Prince (@princeeditor) March 16, 2018