Many More ‘Tulsas’ Are Unknown to Public

- Home page image from Go Fund Me page for Descendants of the Elaine Massacre

Many More ‘Tulsas’ Are Unknown to Public

On Friday, just days after our Journal-isms Roundtable, the Guardian posted this story by Noa Yachot:

“The history of the race massacre in Elaine, Arkansas, has always been contested.

“It is widely accepted that in 1919, a group of white men, with the backing of federal troops, tortured and killed scores of Black residents –- the exact number is disputed but assumed to number at least in the hundreds –- who were starting to organize against the exploitation of their labor. The massacre came at the tail end of what would become known as the ‘red summer’, a season of racial terror fueled by white resentment of the strides Black people were making across the country.

“But at the time, even these basic contours of what happened in Elaine were stricken from the official record. Local authorities spun a tale of a suppressed sharecropper insurrection designed to seize the land of the area’s white planters. As Ida B Wells, the pioneering journalist and anti-lynching advocate would report, more than 100 Black men and women were indicted in this conspiracy theory. Twelve men were sentenced to death, their convictions ultimately overturned by the supreme court. . . .”

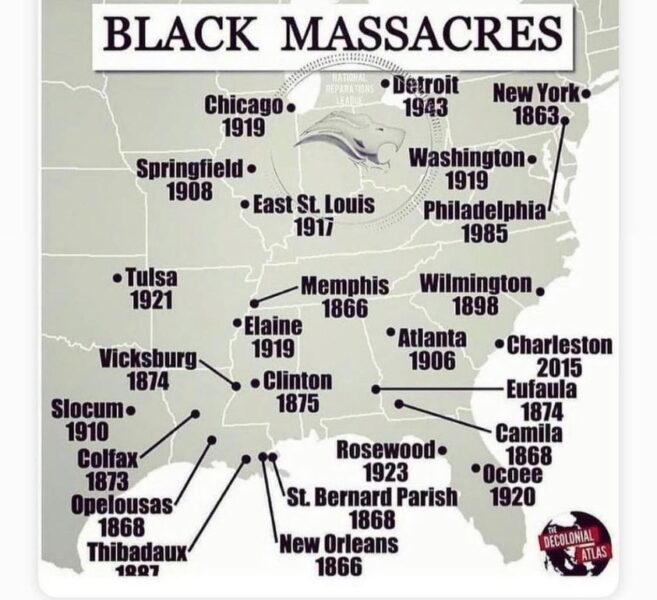

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the nation just commemorated the centennial of a similar atrocity in Tulsa, Okla. Three speakers at our June 13 Roundtable, held by Zoom, either had been on the ground in Tulsa and/or grew up there. They implored their fellow journalists to write about all the other “Tulsas,” such as Elaine, Ark., that are even less well known to the general public, part of what they called a “conspiracy of silence.”

According to the Associated Press, researchers believe that in a span of 10 months in the early 1900s, more than 250 African Americans were killed in at least 25 riots across the U.S. by white mobs that never faced punishment.

Eighty-six people were on the Zoom call, a record for participation in the Roundtables, save for the holiday parties and not counting additional viewers on Facebook Live. It was simultaneously celebratory, inspiring, alarming and chilling.

The speakers were new L.A. Times executive editor Kevin Merida and his wife, writer Donna Britt; DeNeen Brown and Gary Lee, who have been on the ground in Tulsa, Okla., site of the 1921 massacre; columnist Roy S. Johnson, who grew up in Tulsa; new Pulitzer Prize winners Frank Franklin, Associated Press photographer, and Michael Paul Williams, columnist for the Richmond (Va.) Times-Dispatch; and Amber Payne and Bina Venkataraman, representatives of The Emancipator, the new collaboration between antiracism leader Ibram Kendi and the Boston Globe.

You can watch at < https://youtu.be/g1b76WQ6_nQ >

The session opened with an announcement that MSNBC President Rashida Jones, the first African American in that position, had declined an invitation to join us, according to an MSNBC spokeswoman. MSNBC had said that Jones wasn’t doing “interviews,” but then gave an interview to The Washington Post.

[Jones has since said she would look for time on her schedule to join us.]

Host Richard Prince also said that the “Journal-isms” column would be hiring a part-time assistant and that a job description would be posted soon.

“It was 3 hours very well spent,” said Bob Mong, former editor and president of the Dallas Morning News, now president of the University of North Texas at Dallas.

“You’ve got the right people in the room!” said Dave Umhoefer, director of the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University. He was referring to the May roundtable, but he came back for this one.

Brown has been the journalistic point person for reporting on the Tulsa developments.

The New York Post prepared this video about the Elaine Massacre. (Credit: YouTube)

It was Brown’s 2018 story in The Washington Post that brought national attention to the Tulsa Massacre and the search for mass graves. She produced one of the many documentaries and reported on other cities that had experienced similar atrocities. One was Elaine, Ark.

“They’re not as far along as Tulsa in terms of even acknowledging the massacre that occurred in September 1919, and to October 1919. Nor, the state has not investigated what occurred there,” Brown told us.

“And the descendants in Arkansas say that there are mass graves. There may be as many as 800 Black people who were killed during that time . . . I’ve expanded, tried to expand this series of writing to let people know that Tulsa was one of the worst but was not the only massacre.”

Johnson (pictured), a Tulsa native, now a columnist for al.com in Alabama, added, “Beyond the stories that must continue to be told about Tulsa, is that every city has a Tulsa . . . not just massacres but how many thriving Black neighborhoods have been forgotten and left behind and cities throughout America, whether they were dissected by highways just as Greenwood was, or whether the dollars just began to leave the community, whether there was not investment in the community, whether there was not investment in the schools.

Johnson (pictured), a Tulsa native, now a columnist for al.com in Alabama, added, “Beyond the stories that must continue to be told about Tulsa, is that every city has a Tulsa . . . not just massacres but how many thriving Black neighborhoods have been forgotten and left behind and cities throughout America, whether they were dissected by highways just as Greenwood was, or whether the dollars just began to leave the community, whether there was not investment in the community, whether there was not investment in the schools.

“So I encourage every journalist to pursue those untold stories in their cities. Pursue the Tulsa in their city to try to revive and resurrect, not just the stories, but the people who lived in that era, people who were leaders in those neighborhoods.”

Johnson reserved special praise for residents who returned “even though lumber companies would not sell lumber to Black residents to allow them to rebuild their homes that came back, even though brick companies would not sell bricks to residents — Black residents — to allow them to rebuild their homes — even though there was a street that sometimes as Blacks were trying to drive back into Greenwood, into the neighborhood, it was lined by robed Klan members as if they were a welcoming committee daring them to come back and rebuild. So I’ve been lifted by the resilience and the bravery of those people who not just survived, but came back and rebuilt.”

Payne (pictured), coming off a Nieman fellowship, called the Tulsa discussion a “scene setter” for her because she has just been named co-editor of The Emancipator, a collaboration between the Boston Globe and Kendi’s Center for Antiracism Research at Boston University. “How history can really reveal our present is a lot of what we’re going to focus on,” Payne said.

Payne (pictured), coming off a Nieman fellowship, called the Tulsa discussion a “scene setter” for her because she has just been named co-editor of The Emancipator, a collaboration between the Boston Globe and Kendi’s Center for Antiracism Research at Boston University. “How history can really reveal our present is a lot of what we’re going to focus on,” Payne said.

The Emancipator was a Boston-based 19th century abolitionist newspaper. Globe Editorial Page Editor Venkataraman said that as the George Floyd protests continued throughout 2020, she and colleagues thought, “Let’s do something equivalent today for the coverage of racism, which is [to] reframe the conversation with an opinion-and-ideas journalism approach to ask, how are we going to bring about a racially just society? How can we help people imagine it? What are the solutions that need to be debated? How can we show people alternatives to the systems and structures we have today?”

Venkataraman praised Mariette DiChristina, dean of the Boston University College of Communication, who was also on the call and “championed” the idea. Payne said the publication would be hiring, but the job descriptions have not yet been finalized.

We took time to celebrate the newest Pulitzer Prize winners, including that for commentary, Michael Paul Williams (pictured) of the Richmond (Va.) Times-Dispatch. The Pulitzers were announced the previous Friday and Williams was cited for his columns that attempted to answer those same questions Venkataraman raised.

We took time to celebrate the newest Pulitzer Prize winners, including that for commentary, Michael Paul Williams (pictured) of the Richmond (Va.) Times-Dispatch. The Pulitzers were announced the previous Friday and Williams was cited for his columns that attempted to answer those same questions Venkataraman raised.

“It’s kind of a crazy moment, and there’s been a lot of change, and a lot of aspiration toward change over the last year, and I think Richmond embodies that as much as any city in the country,” Williams told us.

“And I’ve been proud to say I think the Times-Dispatch, more so than [at] any point in this history, has attempted to be an honest broker in capturing that in an authentic way. . . .

“So, the paper’s real excited. The paper is very much aware of its legacy, its very troublesome legacy when it comes to race.

“And there are people there, honestly, attempting to change that narrative, but it’s gonna be a long, long slog.

“But the acknowledgement is the first step and we’re doing that work. . . .

“People in Richmond, especially African Americans, but all people of all colors and backgrounds, are just excited about the symbolism of it, I guess, and what it could mean as we try to transform ourselves into a different kind of place than the former capital of the Confederacy and all that entails.”

The Times-Dispatch devoted its Saturday front page to Williams’ Pulitzer achievement.

Seeing Williams and Frank Franklin (pictured), part of the APs team that won a Pulitzer for breaking news photography (and who was hired there by Roundtable regular Fred Sweets, who was on the call) prompted Monroe Anderson to write in the chat room, “From when I started 51 years ago as the first black reporter at the National Observer to this session, I am heartened by all the progress that’s been made. We still have a ways to go but we must cherish what hard work and unleashed talent has gotten us to where we are right now. . . .”

Seeing Williams and Frank Franklin (pictured), part of the APs team that won a Pulitzer for breaking news photography (and who was hired there by Roundtable regular Fred Sweets, who was on the call) prompted Monroe Anderson to write in the chat room, “From when I started 51 years ago as the first black reporter at the National Observer to this session, I am heartened by all the progress that’s been made. We still have a ways to go but we must cherish what hard work and unleashed talent has gotten us to where we are right now. . . .”

That progress included the appointment of Merida as executive editor of the Los Angeles Times, who appeared for an off-the-record exchange along with his wife, Britt. Merida started June 1.

Britt said she would continue writing, and Merida fielded questions about his vision for the Times, the new era of multimedia news operations; reaching community members who don’t read the Times; the continuing need for good writing; and how the Times might become a model for covering multicultural communities.

Merida also said of the journalists, “You unlock people’s genius. And so that’s what we have to do more for ourselves and for each other.”

That prompted Brown to remark in the chat room, “This is a great quote, Kevin. Thank you!”

Former NPR reporter Nolu Crockett-Ntonga asked how Brown maintains her mental health amid coverage of Tulsa, police killings of Black people and Blacks killing other Blacks.

Brown said she does it for the ancestors.

“We Black people know that our ancestors cry out to us. And if you’re open and you hear them, and you’re obedient and you do the work that they asked you to do. Again, my people are from Oklahoma.

“My father is a descendant of a Creek Freedman. My great-grandmother lived in Tulsa. My grandmother, you know, was born in [the all-Black Oklahoma town of] Boley. I was born in Oklahoma, so it’s like when I went there for the first time, I described having lunch with my dad on Black Wall Street . . . .

“I could feel it. You know how old Black people were like, ‘I could feel it in my bones.’ I can feel that this place was haunted. So any time I get tired, you know, of writing these stories — and I don’t — I’m reminded of what our people have endured, the resilience and the power of our people. We come from a mighty people. . . .

“I write the story, I write the story, I write the story. I pursue the truth. I’m an old reporter. Anybody knows me, I’m a street reporter straight up. Never at my desk. . . .

“We have to tell it. We have to tell the story, so that this history is not forgotten, because they whitewashed it out of our history for, I don’t know how many years. Yeah, we knew the story. . . . So, that is the mantra that I hear my head. ‘Tell it, DeNeen. Tell it, tell it.’ “

- Joie Chen, “Matter of Fact with Soledad O’Brien”: The Generational Trauma Left by the Most Violent Election Day in U.S. History (May 23)

- Tiffany Cross, The Cross Connection, MSNBC: @TiffanyDCross gives Sen. Lindsey Graham a much needed history lesson. (Twitter, March 13)

- Brandon Mulder, American Prospect: Arkansas Residents Make a Case for Reparations 100 Years After the Elaine Massacre (Sept. 30, 2019)

- The New Yorker Radio Hour: “The Newspaperman Who Championed Black Tulsa” (podcast)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2017 — Where Will They Take Us in the Year Ahead?

- Book Notes: Best Sellers, Uncovered Treasures, Overlooked History (Dec. 19, 2017)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2016

- Book Notes: 16 Writers Dish About ‘Chelle,’ the First Lady

- Book Notes: From Coretta to Barack, and in Search of the Godfather

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

- “JOURNAL-ISMS” IS LATEST TO BEAR BRUNT OF INDUSTRY’S ECONOMIC WOES (Feb. 19, 2016)

- Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault,“PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World

- Book Notes: Hands Up! Read This!

- Book Notes: New Cosby Bio Looks Like a Best-Seller

- Journo-diversity advocate turns attention to Ezra Klein project (Erik Wemple, Washington Post, March 5, 2014)