Speak Up; Don’t Let Trump Control the Narrative

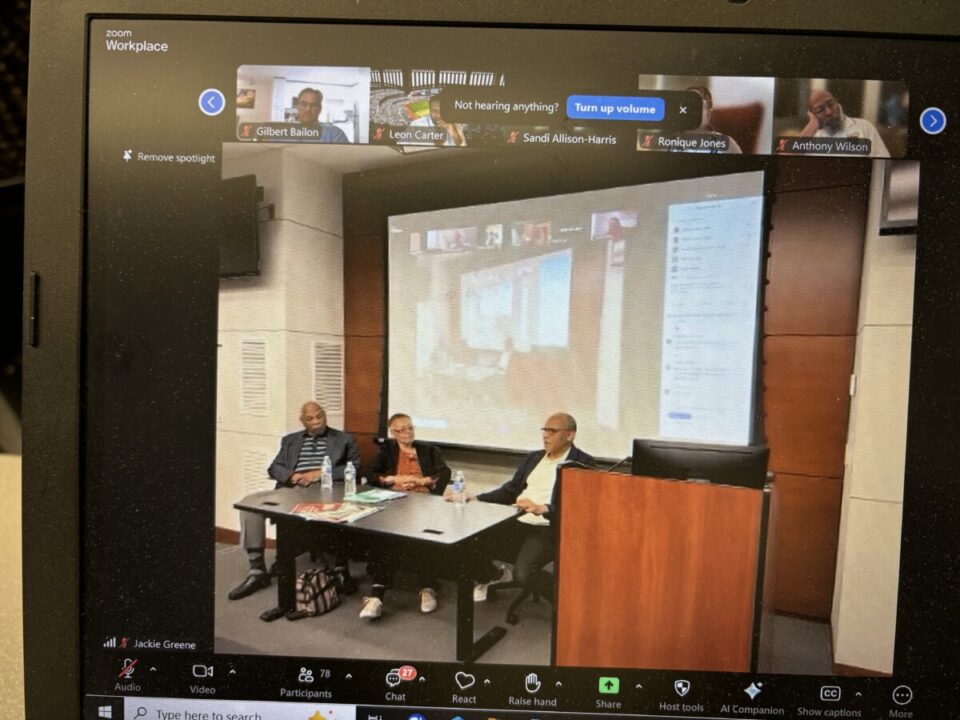

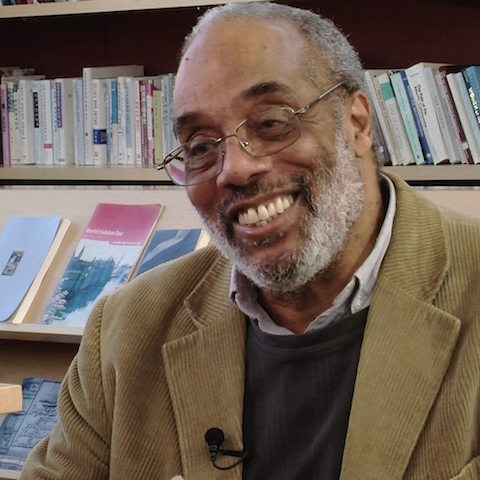

Homepage photo: Courtland Cox, left, Judy Richardson and Eugene Robinson at George Washington University for the April 30, 2025, Journal-isms Roundtable (Credit: Richard Prince)

Support Journal-ismsDonations are tax-deductible

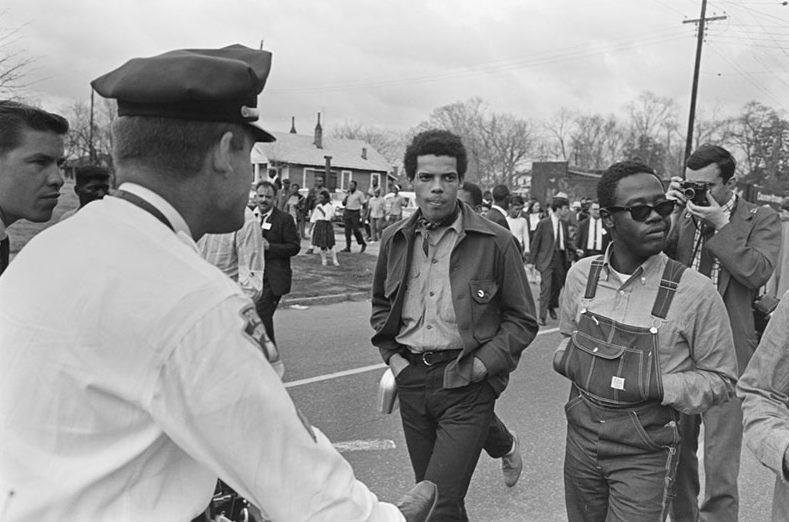

SNCC-affiliated protesters march in Montgomery, Ala., March 17, 1965 (Credit: Library of Congress, Glen Pearcy Collection) This year, the SNCC Legacy Project produced a video, “‘It’s Dark, But It’s Not Midnight.”’

Speak Up; Don’t Let Trump Control the Narrative

By Tolu Olasoji

On April 30 — exactly 100 days into President Trump’s second term — veterans of the civil rights movement convened at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs to address a pressing question: How can journalists counter an administration actively reshaping historical narratives and dismantling racial equity initiatives?

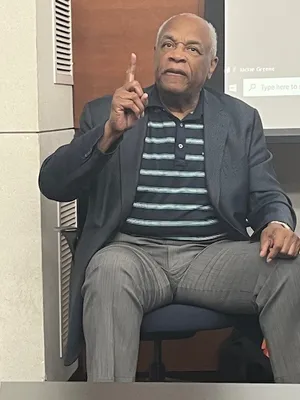

“When you control definitions, you control the narrative,” said Courtland Cox (pictured, by Deborah Barfield Berry/USA Today), chairman of the SNCC Legacy Project, an outgrowth of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Cox set the tone for the hybrid Zoom-and-in-person Journal-isms Roundtable, “What the Civil Rights Movement Teaches Journalists About Dealing with Trump and Trumpism.”

“When you control definitions, you control the narrative,” said Courtland Cox (pictured, by Deborah Barfield Berry/USA Today), chairman of the SNCC Legacy Project, an outgrowth of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Cox set the tone for the hybrid Zoom-and-in-person Journal-isms Roundtable, “What the Civil Rights Movement Teaches Journalists About Dealing with Trump and Trumpism.”

Cox was joined by fellow panelists Andrew Young, lieutenant to Martin Luther King Jr, former U.N. ambassador and a former mayor of Atlanta, and SNCC Legacy Project colleagues Judy Richardson and Charles Cobb.

The chairman’s statement reflected the evening’s urgent focus: journalism’s role when truth itself is contested territory.

Cox also said, “the ongoing battle cannot be understood if journalists [see] the power center of Washington as the place to capture and understand the story of what is taking place today. The journalists need to get outside of Washington to talk to the people who are dramatically being impacted by the decisions being taken in support of MAGA.

“The fight is not between the Democratic and/or Republican Party. The fight is about minority rule to advance the interest of a small number of wealthy people versus the food, shelter, health and clothing needs of the majority of Americans.

“Rachel Maddow of MSNBC is an example that journalists might want to emulate. She has focused much of her programming about what is happening outside of Washington as Americans try to make sense and resist the MAGA objectives.”

Cobb, former SNCC field secretary, told the group that “the journalism organizations like NABJ or or any of these have the muscle to really make these kinds of struggles legitimate,” but that for all the assault, I don’t know what the NABJ” is doing, “whether they’ve made a statement, for instance, on this whole assault on the Smithsonian.” Cobb was referring to the National Association of Black Journalists, of which Cobb is a co-founder, and Trump administration threats to remove content from the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“I don’t think there’s that exercise that’s been going on. I don’t know if the NABJ worries aloud about the issues of democracy that will threaten Black people first.

“So they start sending people to gulags, you can bet it’s going to be y’all.”

Among the participants were six co-founders of the National Association of Black Journalists: Maureen Bunyan, Charles Cobb, Joe Davidson, Leon Dash, Allison Davis and Sam Ford, but no current NABJ board members. (Credit: YouTube)

The session was one of the most well-attended since the Roundtables began in 1999, with 92 people in person or on the Zoom call and 223 tuning in on Facebook (where there were technical difficulties). Ninety-four had watched the video of the Roundtable on YouTube as of May 4, and another 89 called up a separate video honoring Kenneth Walker, the Emmy-winning ABC News and NPR correspondent who died April 11.

In addition, the Roundtable provided grist for a story published in USA Today on May 4, “Trump’s early agenda dismantles Civil Rights Act, advances Project 2025, activists say,” by attendee Deborah Barfield Berry.

Also part of the discussion were:

- Benjamin F. Chavis, Jr., DMin, president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association.

- Charlayne Hunter-Gault, veteran journalist and school desegregation pioneer.

- Angela Greiling Keane, president of JAWS (Journalism & Women Symposium) and news director at Bloomberg Government.

- Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely, grandniece of William Monroe Trotter (1872-1934), activist editor of the Boston Guardian.

- Carole Simpson, retired weekend anchor at ABC News who covered the Movement for WBBM and WMAQ in Chicago

The session opened with tributes to two journalistic pillars: Walker, who was remembered for his fearless reporting on apartheid and across the African continent. Then a toast to Eugene Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist who recently departed the Washington Post.

Discussion of Walker, which included a video prepared by D.C. broadcast veterans Maureen Bunyan and Sam Ford, continued after the Roundtable, as the Washington Post at first declined to publish an obituary of him, then changed course after its decision was publicized among Post alumni and Roundtable participants.

Robinson (pictured), who counted himself among those whom Walker mentored while at the Washington Star, elaborated publicly for the first time on his resignation from the Post, announced April 3. The columnist explained that his decision to leave a place where he intended to “keep bearing witness to what was going on” came after controversies that trailed the news outlet in the lead-up to the 2024 election.

Robinson (pictured), who counted himself among those whom Walker mentored while at the Washington Star, elaborated publicly for the first time on his resignation from the Post, announced April 3. The columnist explained that his decision to leave a place where he intended to “keep bearing witness to what was going on” came after controversies that trailed the news outlet in the lead-up to the 2024 election.

Billionaire owner Jeff Bezos blocked the Post’s planned endorsement of Democratic candidate Kamala Harris.

Three months ago, Bezos announced he wanted a “significant shift” in the paper’s opinion section, to focus exclusively on “personal liberties and free markets,” with viewpoints opposing those principles “left to be published by others.”

“It came right after the Post took a tougher line on Trump — including an $11 billion AWS [Amazon Web Services] contract dispute,” Robinson explained. The shift prompted immediate resignations, including that of Opinion Editor David Shipley.

“That was it for me,” Robinson said. “I could no longer work under those terms.”

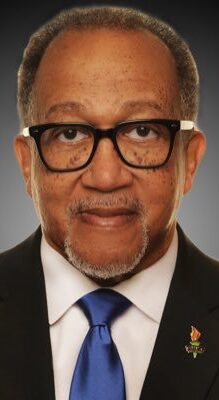

This concentration of media power in billionaire hands stood in stark contrast to another tradition represented at the Roundtable. Chavis (pictured), president of the NNPA, trade association for Black-press publishers, told the audience that 255 Black-owned newspapers have long served as bulwarks against misinformation and tools to counter mainstream narratives.

This concentration of media power in billionaire hands stood in stark contrast to another tradition represented at the Roundtable. Chavis (pictured), president of the NNPA, trade association for Black-press publishers, told the audience that 255 Black-owned newspapers have long served as bulwarks against misinformation and tools to counter mainstream narratives.

These publications — including the Pittsburgh Courier, Chicago Defender, New York Amsterdam News and Atlanta Voice — have historically played a different role from white-owned outlets.

Chavis delivered a pointed reminder of Black newsrooms’ unique responsibility. “The role of journalists, Black journalists, is different from the role of white journalists,” he said, arguing that from the civil rights movement to the present day, “we live in a society that is permeated by white supremacy. Those laws… the society doesn’t give the quality of life or the humanity of Black people what they deserve. And that humanity is only going to get the coverage, only going to get the definition if we do it ourselves.”

Cox’s statement about controlling definitions was relevant to recent news coverage. Just days earlier, ABC News correspondent Terry Moran had fact-checked President Trump during an interview about Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Maryland man mistakenly deported to El Salvador. When Trump insisted that Garcia had “MS-13” tattooed on his knuckles, Moran pointed out: “That was Photoshopped.” He explained that the letters and numbers had been digitally added to a photograph of Garcia’s hand. Trump and his supporters insisted Garcia’s supposed gang affiliation should supersede what they called the misleading description “Maryland man.”

“Who gets to define us in this country, as African Americans?” Cox asked the assembled journalists. “For me, in terms of the lesson I learned from the civil rights movement, is that you have to set the definition. Because who controls the definition gets to decide.”

Expanding on the idea, Preacely (pictured) , a former SNCC activist and great-grandniece of journalist Trotter, pointed out how a single phrase can signal deeper intent. She recalled that once officials began describing García as “incorrectly deported,” listeners immediately sensed something was off. “That one-word thing — ‘incorrectly deported so-and-so Garcia’ was really key,” she said, because “automatically every time you heard Garcia, you knew, ‘Oh, that was not done right.’ ‘”

Expanding on the idea, Preacely (pictured) , a former SNCC activist and great-grandniece of journalist Trotter, pointed out how a single phrase can signal deeper intent. She recalled that once officials began describing García as “incorrectly deported,” listeners immediately sensed something was off. “That one-word thing — ‘incorrectly deported so-and-so Garcia’ was really key,” she said, because “automatically every time you heard Garcia, you knew, ‘Oh, that was not done right.’ ‘”

Cobb (pictured) said he faced similar semantic tug-of-wars as an international reporter, remembering his days covering Angola.

Cobb (pictured) said he faced similar semantic tug-of-wars as an international reporter, remembering his days covering Angola.

He recounted how an editor insisted on branding one faction “the communist MPLA [People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola].” Cobb responded that if he had to tag one side, “I’m going to call the FNLA ‘the capitalist FNLA’ [National Front for the Liberation of Angola]” and that “ended the discussion.”

The Roundtable participants drew parallels to how media framing shaped public perception during earlier civil rights struggles. Even ostensibly neutral coverage can inadvertently strengthen an administration’s intent through uncritical adoption of official language, they said.

One stark historical example came from Birmingham, Ala., in 1963, when the city’s white-owned newspapers refused to run the now-iconic photographs of police dogs attacking Black children during protests — images that transformed national understanding of the movement. While international audiences witnessed these brutal manifestations of segregation, Birmingham’s mainstream papers not only omitted the photographs but typically refused to quote Black leaders or even print the names of African Americans pictured in photos on general news pages.

In January, Minnesota residents called for a nationwide boycott of Target stores in response to the corporation cutting its diversity, equity and inclusion policies. (Credit: Unicorn Riot)

This selective framing remains relevant today as journalists navigate how to cover administration policies without amplifying misleading narratives. After the Roundtable, Jack White, a retired Time magazine columnist who attended the session, emphasized the distinction journalists must navigate: “There’s a difference between clarity and advocacy, and journalists must always be aware of it. Tricky, but necessary.” He noted that the media “play a crucial role in framing the issue and allowing people to understand the stakes and which side they are on.”

The question of how Black media should respond to an administration seen as hostile to civil rights continued the discourse on definitional power and framing.

“In our definitions, how do we define white supremacy? How do we define racism?” Chavis asked. He argued that Black outlets must establish their own frameworks rather than accept terminology imposed by others in a white-dominated field, especially when covering an administration that is keen on redefining basic concepts of citizenship and belonging.

This battle over language isn’t merely theoretical. Journalist Roger Witherspoon pointed to historical blind spots that continue to shape American understanding of its own past. “Most people still don’t know the names of the . . . Black men” killed alongside white civil rights workers in Mississippi, Witherspoon noted, because mainstream reporters “covered only the white victims.” Such selective attention makes independent Black media essential to completing the historical record.

PBS’ “American Experience” later reported of that 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, “Throughout July, investigators combed the woods, fields, swamps, and rivers of Mississippi, ultimately finding the remains of eight African American men. Two were identified as Henry Dee and Charles Moore, college students who had been kidnapped, beaten, and murdered in May 1964. Another corpse was wearing a CORE t-shirt. Even less information was recorded about the five other bodies discovered.”

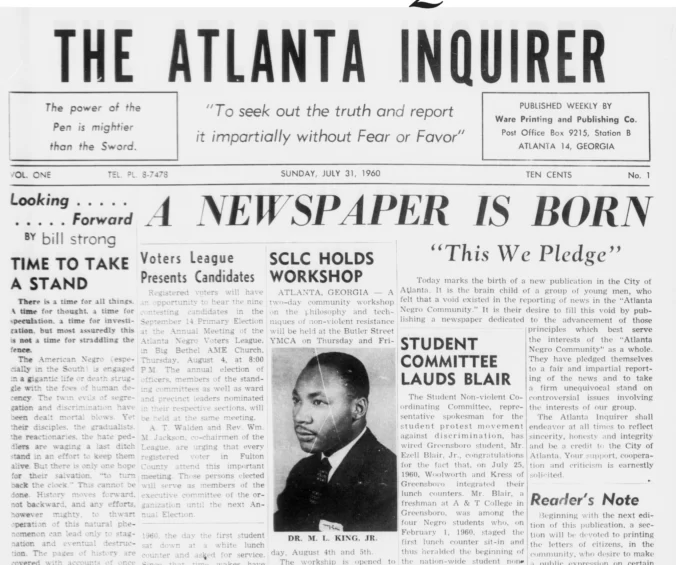

First edition of the Atlanta Inquirer, July 31,1960.

Economic pressures have, however, often complicated this mission. Richardson noted that when Atlanta’s major Black newspaper, the Atlanta Daily World, refused to cover civil rights protests during the 1960s for fear of alienating white advertisers, activists created their own media infrastructure. Hunter-Gault described how the Atlanta Inquirer was established by Julian Bond, SNCC activist and later state legislator and NAACP leader, and Clark College professor M. Carl Holman, because “nobody else was telling our stories.” She recalled driving long miles each weekend to work in its newsroom..

This tradition of filling critical gaps in coverage has continued across generations. Barbara A. Reynolds (pictured), who has since added “the Rev.” and a doctor’s degree in ministry to her name, launched Dollars & Sense magazine after noticing that John H. Johnson’s founding of Ebony magazine received no attention in mainstream business sections. Her publication spotlighted Black executives, educators and labor leaders because these voices were “crucial to Chicago’s strength,” yet invisible to readers who “only saw Black people as criminals or tenants.”

This tradition of filling critical gaps in coverage has continued across generations. Barbara A. Reynolds (pictured), who has since added “the Rev.” and a doctor’s degree in ministry to her name, launched Dollars & Sense magazine after noticing that John H. Johnson’s founding of Ebony magazine received no attention in mainstream business sections. Her publication spotlighted Black executives, educators and labor leaders because these voices were “crucial to Chicago’s strength,” yet invisible to readers who “only saw Black people as criminals or tenants.”

The Roundtable participants emphasized that today’s challenges demand renewed infrastructure and strategy. Pointing to the conservative “Project 2025” blueprint, Chavis challenged his colleagues: “Where’s our Project 2026? Where’s our Project 2028?” He clarified this wasn’t about imitation but preparing for sustained resistance: “What I’m saying is, we do have to have a plan.”

According to Mark Williams, opinion editor, opinion writer and news editor, formerly of the Baltimore Banner, that plan must be collective. “Standing against attacks on our rights requires action that crosses institutions, generations, and perspectives within our community,” he said.

The stakes extend beyond policy to cultural memory itself. “They’re moving to defund our museums, to erase our heroes and sheroes,” Chavis warned, describing efforts that “aren’t merely disputes over budgets” but attempts to “demean our humanity.”

Richardson (pictured, flanked by Courtland Cox and Eugene Robinson, by Richard Prince) , board member of the SNCC Legacy Project and co-producer of the landmark documentary series “Eyes on the Prize,” provided tangible evidence of youth activism by holding up a newspaper. “Most of us were 17, 18, 19 years old when we did this,” she said. “That’s why I show it in every class — to prove we were your age doing what you’re covering today.” Currently co-directing the new visitor film center for the National Park Service’s Frederick Douglass House in Washington, D.C., Richardson personifies the ongoing work of protecting historical narratives against erasure.

The civil rights movement itself transformed American understanding of press freedom. The movement’s strategic use of media and its challenges to biased coverage helped redefine First Amendment protections. By forcing news organizations to confront their own biases in coverage, civil rights activists expanded the very concept of what constitutes a free press, a legacy that remains vital (but threatened by the current administration) as journalists navigate today’s complex media landscape.

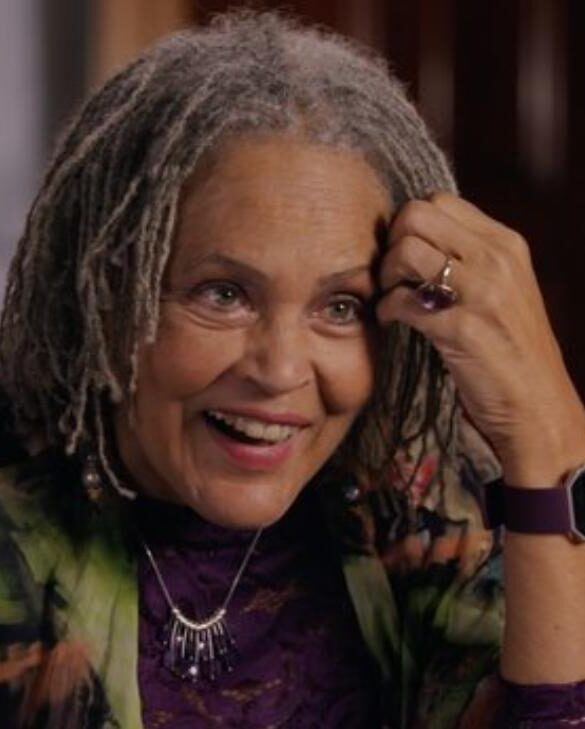

Hunter-Gault (pictured), in 1961 became one of the first two Black students to integrate the University of Georgia before launching a distinguished career in journalism. She called for what she termed “a coalition of the generations.”

Hunter-Gault (pictured), in 1961 became one of the first two Black students to integrate the University of Georgia before launching a distinguished career in journalism. She called for what she termed “a coalition of the generations.”

“I’m again calling for a coalition of the generations so that we can bring together the older people like myself and Andy (Young),” she said.

After the Roundtable, Reynolds recalled advice from her mentor Ethel Payne of the Chicago Defender, who echoed the words of Frederick Douglass: “Agitate, agitate, agitate, agitate.” Reynolds recounted a powerful moment when Ida B. Wells’ daughter visited her at the Chicago Tribune, where Reynolds was being “disdained as an affirmative action hire.”

“She told me she was the daughter of the celebrity journalist Ida B. Wells,” Reynolds wrote. “She told me I had the courage of her mother (nicknamed) Iola. And if I could just do my best under fire, one day it would NOT be just me sitting alone and underappreciated in a white newspaper. There would eventually be hundreds.”

She reminded Reynolds that her mother “had to come in the Tribune dressed as a maid, but at least I was there at a desk and a typewriter.” Reynolds reflected: “This kind of support I hope we find a way to pass on to the next generation. We still need each other.”

John Yearwood, a veteran editor and newsroom leader, said afterward that Young was urging journalists to “find our North Star. They did in Atlanta and built the busiest airport in the world.” Young was saying, “When things get tough, work to make a difference where you can. And if everyone is able to focus on the piece they can change, bigger societal change will happen.”

Cobb urged newsrooms to sharpen their focus on democracy under attack. “Journalists, and particularly Black journalists, have to give much more visibility to the assault being made on democracy,” he said. He called out “Nazi sympathizers claiming to be fighting anti-Semitism” and “segregationists claiming the removal of Black history is inclusion,” insisting that such distortions require a relentless “drumbeat” of challenge.

Jill Geisler (pictured), the Bill Plante Chair in Leadership and Media Integrity at Loyola University Chicago, distilled the discussion’s core lessons: “The power of words, the framing of stories, and the power of individuals, with or without formal leaders.”

Jill Geisler (pictured), the Bill Plante Chair in Leadership and Media Integrity at Loyola University Chicago, distilled the discussion’s core lessons: “The power of words, the framing of stories, and the power of individuals, with or without formal leaders.”

As the Roundtable drew to a close, Young (pictured), 93, offered a quote from King: “Truth forever on the scaffold. Wrong forever on the throne. Yet that scaffold sways the future. For behind the dim unknown. Standeth God within the shadows. Keeping watch above his own.”

As the Roundtable drew to a close, Young (pictured), 93, offered a quote from King: “Truth forever on the scaffold. Wrong forever on the throne. Yet that scaffold sways the future. For behind the dim unknown. Standeth God within the shadows. Keeping watch above his own.”

As Preacely, Trotter’s grandniece and herself a poet, wrote in a recent work she shared after the Roundtable:

“We will not be co-opted… erased… dismissed… ignored…. we have been down this same road… so many times before. But today we stand resilient…. and more determined to our core.”

The Roundtable speakers were united on this takeaway: The tools developed during the civil rights movement remain essential for journalists navigating an era when truth itself is contested territory and threats loom over hard-fought civil rights. These veterans offered not just warnings but a time-tested strategy: Control your own definitions, preserve your own history, and build coalitions across generations.

Tolu Olasoji is a New York-based producer/journalist and member of the New York Association of Black Journalists.

- David Bauder, Associated Press: After a year of turmoil, The Washington Post is taking note of its journalism again

- Committee to Protect Journalists: CPJ joins coalition urging Congress to preserve public broadcasting funding

- Journal-isms: NABJ Strategy: Circumvent Anti-DEI Backlash (scroll down) (March 17)

- Journal-isms: Jesse Jackson: ‘You Work in Pain’ Speech at the NABJ convention in 1984 in which he said journalists have “appraisal power.” (April 7, 2018)

- Kenneth B. Morris Jr., Frederick Douglass descendant: What Would Frederick Douglass Think? (Feb. 28)

To subscribe at no cost, please send an email to journal-isms+subscribe@groups.io and say who you are.

Facebook users: “Like” “Richard Prince’s Journal-isms” on Facebook.

Follow Richard Prince on Twitter @princeeditor

Richard Prince’s Journal-isms originates from Washington. It began in print before most of us knew what the internet was, and it would like to be referred to as a “column.” Any views expressed in the column are those of the person or organization quoted and not those of any other entity. Send tips, comments and concerns to Richard Prince at journal-isms+owner@

View previous columns (after Feb. 13, 2016).

View previous columns (before Feb. 13, 2016)

- Diversity’s Greatest Hits, 2018 (Jan. 4, 2019)

- Book Notes: Is Taking a Knee Really All That? (Dec. 20, 2018)

- Book Notes: Challenging ’45’ and Proudly Telling the Story (Dec. 18, 2018)

- Book Notes: Get Down With the Legends! (Dec. 11, 2018)

- Journalist Richard Prince w/Joe Madison (Sirius XM, April 18, 2018) (podcast)

- Richard Prince (journalist) (Wikipedia entry)

- February 2018 Podcast: Richard “Dick” Prince on the need for newsroom diversity (Gabriel Greschler, Student Press Law Center, Feb. 26, 2018)

- An advocate for diversity in the media is still pressing for representation, (Courtland Milloy, Washington Post, Nov. 28, 2017)

- Morgan Global Journalism Review: Journal-isms Journeys On (Aug. 31, 2017)

- Journal-isms’ Richard Prince Wants Your Ideas (FishbowlDC, Feb. 26, 2016)

-

Richard Prince with Charlayne Hunter-Gault, “PBS NewsHour,” “What stagnant diversity means for America’s newsrooms” (Dec. 15, 2015)

- Book Notes: Journalists Follow Their Passions

- Book Notes: Journalists Who Rocked Their World